Founders front and center at 2010 Shurden Lectures

From Montesquieu to Madison, Marty focused on wise words and church-state separation

By Mary L. Wimberley, Samford University

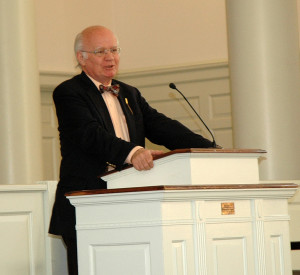

Martin E. Marty, a prominent interpreter of religion and culture, drew on historical episodes and figures such as Montesquieu, Benjamin Franklin and James Madison to clarify aspects of religious liberty and church-state separation for audiences at Samford University April 27-28.

His presentations were part of the annual Walter B. and Kay W. Shurden Lectures on Religious Liberty and Separation of Church and State, a series sponsored by the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty and hosted by Samford.

Supporting the separation of church and state does not mean being against religion, Marty said.

“There are strong impulses in society to say that you serve religion by protecting and privileging it,” Marty said, but there is a difference in protection and privilege, which is defined as a right or immunity granted as a benefit. “There are all kinds of ways to protect religion without privileging it,” he said.

Marty told how 18th century French philosopher Montesquieu, who wrote that religion is more harmed than helped by favoritism, influenced the writers of the U.S. Constitution on matters of separation of church and state.

“Montesquieu never visited America, but they were reading him,” he said of the 55 founders who gathered in Philadelphia, Pa., for the Constitutional Convention.

In his writings, George Washington used 28 different names for God, such as First Architect, but not one was biblical, Marty said. “They were looking for language that would enlarge the context.”

The founders, he said, solved the religion problem by not solving the religion problem. Marty, an ordained Lutheran minister who taught for 35 years at the University of Chicago, told how the writings and beliefs of Franklin and Madison played roles in religious liberty during the three-part lecture series.

To some extent, the quality of indifference, such as that exhibited by Franklin, contributed to the lack of religious references in the Constitution, he said.

Franklin was religious, but didn’t like the dogma associated with it. Nor did he like defining religions, and opposed zealotry and fanatics, Marty said, noting that zealousness and difference both play a large role in religion.

“Religion in the end almost always calls for profound, sustained passionate commitment,” said Marty.

A degree of indifference helped move along the framing of the Constitution, which involved people who had convictions, but who had to make decisions and eventually go home.

Although Franklin once questioned why the Framers did not have morning prayers to help them in their task, the idea was scuttled, in part because there were no funds for a chaplain.

Also, Marty said, the Framers knew it would get them in a dilemma. “They were passionate people, but they knew that introducing religion into the setting would get them in trouble.” The situation, he said, “was a close-up of how it would be in the republic.”

Madison predicted that it would be difficult to trace a line of separation between the rights of religion and civil authority without collisions and doubts. And although little is known about his religious stand as an adult, Madison saw no need for a religious protection clause in the Constitution, but later became a key figure in writing the First Amendment.

Marty said it is not easy to trace the line of distinction, citing current court cases such as those involving military endorsement of chaplains and lobbying by Catholic bishops on healthcare reform.

“Madison anticipated that it would be impossible to trace a line of distinction in all cases,” Marty said. “A wall may be slender and have holes, but it’s a wall. Madison said that a line wasn’t something you could storm. And, you could see people on the other side.”

“Separation is important, and whenever we talk of convergence we must recognize potential problems,” Marty said. He continued by saying that Madison advised defending rights of religion, but not privileging religion.

While at Samford, Marty and the BJC staff spoke to several different student groups and classes, including history, religion and media classes. BJC General Counsel Holly Hollman and Staff Counsel James Gibson also led a joint political forum with Samford’s College Democrats and College Republicans.

The annual lectureship was established in 2004, when the Shurdens, of Macon, Ga., made a gift to enhance the programs of the Baptist Joint Committee. The lectures are held at Mercer University in Macon every three years and at another seminary, college or university in other years. The Shurdens both taught at Mercer for many years.

The 2011 Shurden Lectures will be on the campus of Georgetown College in Georgetown, Ky. The series will return to Mercer in 2012.

Listen to the podcast Return to main Shurden Lectures page

[ylwm_vimeo]11532968[/ylwm_vimeo]

[ylwm_vimeo]11551664[/ylwm_vimeo]

[ylwm_vimeo]11561067[/ylwm_vimeo]