A memorial service for James M. Dunn was held Saturday, July 18, at 11 a.m. at Knollwood Baptist Church in Winston-Salem, N.C. Click here to watch a video of the entire memorial service.

For more on his life and legacy, visit BJConline.org/JamesDunn. Also, there is a special section devoted to Dr. Dunn in our July/August 2015 Report from the Capital.

Click here to make a donation to the James M. Dunn Next Generation Fund.

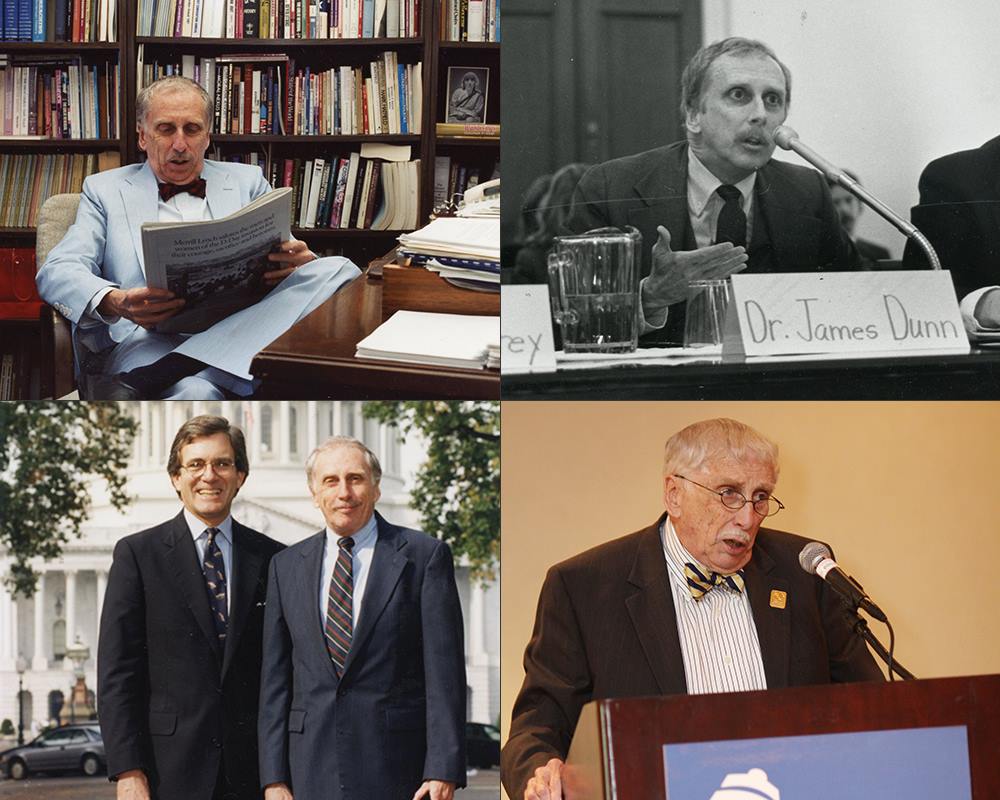

James M. Dunn, the firebrand Baptist who led the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty for nearly two decades, died on July 4 at the age of 83. Known for his stalwart defense of religious liberty, colorful turns of phrase and ubiquitous bow tie, Dunn will be remembered for his contributions throughout Baptist life, including his leadership of the Baptist Joint Committee through the 1980s and 90s. He consistently fought for a strong Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause while simultaneously shepherding the organization through a tumultuous time in Baptist denominational history.

“The 20th century had no greater champion of religious freedom – of conscience – than James Dunn,” said Oliver “Buzz” Thomas, who served as general counsel of the Baptist Joint Committee under Dunn from 1985-1993. “Like Roger Williams, John Leland, George W. Truett and the other great Baptist leaders before him, James understood the dangers of civil religion.”

Dunn wore many hats in Baptist life, including serving as a pastor, campus minister, college and seminary professor, and executive director of the Christian Life Commission of the Baptist General Convention of Texas. In 1980, he was named the 4th executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee (BJC) and assumed his duties in Washington, D.C., on January 1, 1981.

Dunn promised an “aggressive, broad-based” approach in his new position, and he delivered.

“Comfortable in his own skin and serenely secure of who he was at his core, James surrounded himself with talented people who brought their best energies to the task of protecting and enhancing religious liberty in the most religiously diverse nation on Earth,” said Stan Hastey, who worked with Dunn at the BJC for almost a decade.

In his first column for the BJC’s magazine, Report from the Capital, Dunn wrote, “To translate the revealed message of God’s love into public policy is a massive and sometimes tricky undertaking but our generation is not the first to try. God’s children have been bringing morality to public life for centuries. Christian social ethics is a well developed discipline, not merely a collection of reactions to news reports.” He noted that faith in the God of the Bible “will continue to be the hallmark” of the BJC.

In the early 1980s, Dunn’s focus at the BJC centered on opposing an ambassador to the Vatican, fighting against a constitutional prayer amendment and working to pass the Equal Access Act. Believing government intrusion was a violation of soul freedom, Dunn consistently led the BJC in its commitment to the Baptist tradition of true religious liberty for all and guarding the separation of church and state.

“James Dunn came to the Baptist Joint Committee at precisely the right time,” Hastey said. “Coming to the nation’s capital the same month Ronald Reagan was inaugurated as president, James instantly was thrown into battle with a new administration committed to a fundamental alteration in church-state relations.”

Dunn was not afraid to stand against a Reagan-supported school prayer amendment, which would have tinkered with the First Amendment to encourage government-sponsored prayer in schools. He accused the president of “despicable demagoguery” and playing “petty politics with prayer” with the proposal.

“But, James Dunn didn’t just say ‘no’ to bad ideas,” said Brent Walker, who worked with Dunn for 10 years and succeeded him as executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee. “He also worked to create constitutionally acceptable and common sense solutions.”

In an effort to find an alternative to the prayer amendment, Dunn and the BJC supported the practice of allowing students to gather voluntarily before and after school for prayer and other religious exercises in club meetings. One of Dunn’s friends was Sen. Mark Hatfield, a Republican from Oregon and fellow Baptist, who introduced legislation to make it “unlawful to discriminate against any meetings of students in public secondary schools.” Dunn and the BJC worked tirelessly to see that original proposal pass and become the Equal Access Act of 1984.

Walker noted that Dunn’s method of problem-solving was a hallmark of his leadership. “Dunn rightly criticized President Reagan and his school prayer amendment, and his credibility heightened because he advanced a better idea. Dunn was also willing to work with both sides of the aisle and break from the typical coalition structures,” Walker said.

With the Equal Access Act, Dunn and the BJC’s leadership set the tone for future efforts to urge accommodation of students’ exercise of religion in public schools while fighting state-sponsored religious exercises.

No retrospective on the life of James Dunn and his legacy at the BJC would be complete without noting his guidance during the split in the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC). When Dunn took the reins of the BJC, the organization was supported by nine Baptist bodies, but the SBC was its primary funding source. After years of controversy and a few funding cutbacks, the BJC lost all financial support from the SBC in 1991. In the aftermath, Dunn’s leadership steadied the organization through uncharted waters. The BJC kept its firm commitment to the historic Baptist principle of religious liberty and church-state separation as its funding sources expanded to receive larger support from Baptist state conventions, congregations and individuals.

“I had no sooner arrived on the scene than the SBC defunded the BJC,” Walker remembered. “I figured I’d be the first to be let go. But, James held the staff together – no one was laid off – and he quickly righted the BJC’s finances. It’s not an overstatement to say James saved not only my job, but the BJC itself.”

Today, supported by 15 Baptist bodies, the BJC continues to receive financial support from a variety of sources, including denominational bodies, foundations, churches and individuals.

After the funding shift, the agency achieved one of its greatest legislative accomplishments: passage of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993. It was able to rally a broad coalition around the drive to reinstate religious freedom protections.

“Though small of stature, James was a giant of a man,” Thomas said, who was with the BJC during that time. “He was not afraid to put his job on the line for principle. He did that repeatedly. I know because he also put my job on the line. Repeatedly. And I loved him for it. He made me a better man.”

After retiring as executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee in 1999, Dunn became the Professor of Christianity and Public Policy at the School of Divinity at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C. He continued adjunctive teaching until 2014, nurturing the first generation of students. At Wake Forest, he taught the first ethics and church/state courses, as well as a course called “God and The New York Times: Religion in Contemporary America.” His legacy continues on campus with the James and Marilyn Dunn Chair of Baptist Studies. Established in 2011, the chair provides an ongoing Baptist studies faculty presence at the divinity school.

Despite his accomplishments in Washington, ability to survive and thrive in controversy, unmatched ability to turn a phrase and dapper dress, Dunn is maybe best remembered for his personal touch and willingness to elevate the needs of others above his own, as well as his commitment to the next generation.

“James did exactly what Christ calls us to do: pour out our lives in service to others,” Thomas said. “James poured out his life for freedom, for justice and for truth.”

James is survived by his wife, Marilyn. Walker says she was the love of Dunn’s life.

“They never had children of their own, but he served as a mentor and friend to hundreds, ‘parenting’ an untold number of students, interns, young pastor and children of friends,” Walker said.

In his first column for the Baptist Joint Committee, Dunn wrote, “We need a sense of history. Oversimply, we ought to have a profound awareness of what has gone before.”

Those words ring true as we mourn the passing of a man who did much to impact history, leaving his fingerprints on national affairs and in the individual lives of others as he modeled what it means to provide a consistent Baptist witness in public policy and all aspects of life.

For more on the life of James Dunn, see “James M. Dunn and Soul Freedom” by Aaron Weaver.

Watch James Dunn’s address to the 2011 Religious Liberty Council Luncheon at this link. Aaron Weaver introduces Dr. Dunn at 23:55 in the video.

Written by Cherilyn Crowe

Photos clockwise from upper left: Catching up on the day’s news in the office (late 1990s), testifying against a tuition tax credit for private colleges before the House Budget Committee task force (1983), speaking at the Religious Liberty Council Luncheon (2011), posing with then-General Counsel Brent Walker in front of the U.S. Capitol (early 1990s).