Remembering President Jimmy Carter

BJC Executive Director Emeritus Brent Walker recalls touch points between Carter and BJC over the decades

For more than a century, James E. Carter Jr. incarnated a life of stellar public service and demonstrated how to be a Baptist Christian extraordinaire. He was a friend and supporter of BJC, and his death on Dec. 29 was a solemn loss. I can recall several touch points between Carter and BJC — either due to my direct participation or of which I have reliable knowledge.

Soon after the Carters arrived in Washington in January 1977, they joined the First Baptist Church of the City of Washington, D.C., eight blocks north of the White House.

The Carters thought about keeping their membership back home at Plains Baptist Church. But, reflecting on this decision later, Carter said he remembered the advice of his grandmother who had often instructed, “When you move your cook stove, you move your church membership.”

So, they followed his grandmother’s advice and joined the Baptist church nearest the White House. Nine-year-old daughter Amy quickly made a profession of faith and asked to be baptized.

Although during his campaign Carter had spoken of his Christian faith — such as being “born again” — more freely than any of his recent predecessors, Washington journalists needed some help in understanding the impending Baptist rite.

As a fitting welcome to the Carters, BJC’s director of information services and Baptist Press bureau chief, W. Barry Garrett, was dispatched to tutor the White House press corps on the ordinance of believers’ baptism by immersion in Baptist life.

Amy’s February 6, 1977, baptism by First Baptist’s pastor, the Rev. Dr. Charles A. Trentham, was reported in various media outlets. The New York Times, for example, the next day explained, “Baptism in the Baptist Church is not conducted until it is believed that a child is old enough to understand what he or she is doing.”

It appears Barry Garrett had done some good! But the Times reporter could have used a lesson in Baptist polity: there is no “Baptist Church,” only Baptist churches, some of which are connected in conventions or associations.

The Carter family attended First Baptist faithfully when in residence at the White House, and the new president even taught Sunday school quite often.

Carter was the third Baptist president, after Warren G. Harding and Harry S. Truman. When Bill Clinton — the fourth Baptist president — was elected, First Baptist and BJC co-sponsored an inaugural eve prayer service in the church sanctuary. It was a Baptist-only affair — within the “family,” so to speak — and by invitation only. No press was invited, and no photos were permitted. Hundreds of giddy Baptists packed into the lovely cruciform sanctuary like sardines!

Both former President Carter and First Lady Rosalynn Carter attended, and he spoke along with Bill Moyers, Rep. Barbara Jordan and the Rev. Dr. Gardner Taylor, among others. Christian singer-songwriter Ken Medema composed and sang short ditties on the spot — appropriate to each presentation — and prayers were offered throughout.

Former President Carter expressed delight with the election of another Baptist president (and a Baptist vice-president, Al Gore, to boot!) and reminisced about his family’s days at First Baptist. As Clinton and Gore and the rest of us listened, he shared how he landed at that same church during his presidency thanks to that sage advice from his own grandmother.

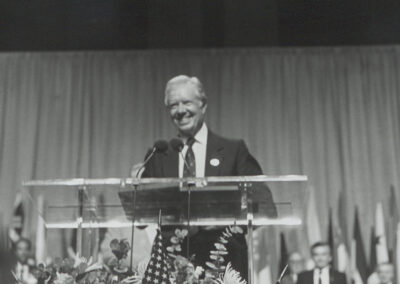

BJC gave President Carter the J.M. Dawson Religious Liberty Award in 1996. It is BJC’s flagship accolade designed to recognize special Baptists who champion religious liberty, defend the separation of church and state, and support BJC’s work. Others receiving the Dawson Award over the years include Bill Moyers, Sen. Mark Hatfield, Rep. Barbara Jordan, Patsy Ayres, Tony Campolo and Bill Leonard.

President Carter’s recognition was special in that it was awarded at the celebration of BJC’s 60th anniversary. Normally, BJC provides a trophy consisting of a crystal flame to recipients, but our physical gift to Carter signifying the award was instead a first-edition book from 1818 authored by William Wilberforce, a British statesman and abolitionist.

Returning the compliment, President Carter praised BJC for embracing and articulating “the principle of the separation between church and state, so that the people who want to worship freely will not be unnecessarily influenced by the government. And on the other hand, that the government should not be interfered with by the church.”

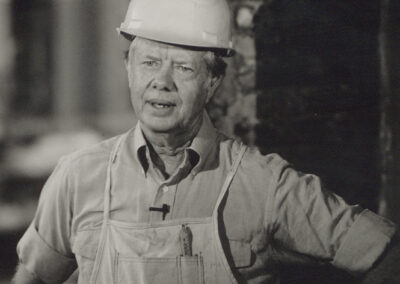

For four centuries, we Baptists have been a clamorous and contentious bunch. We have squabbled with each other as much as we have with outsiders. Maybe more. In the early 2000s, Carter envisioned and then rolled up his sleeves to bring to fruition a pan-Baptist movement of comity and cooperation. It was to be called — and was named — the New Baptist Covenant.

I recall attending a heady meeting at the Carter Center on January 9, 2007, where many gathered to begin planning the effort. Joining former President Carter at the meeting were former President Bill Clinton and Bill Underwood, the president of Mercer University (and the first BJC intern in the early 1980s), along with representatives from 40 groups that spanned the Baptist landscape. The Southern Baptist Convention, unfortunately, chose not to participate.

A year’s work culminated in a three-day convocation and celebration in Atlanta of 15,000 participants enjoying harmonious fellowship, education, worship and planning. Baptist historian Dr. Walter “Buddy” Shurden called it “a major step in racial reconciliation and gender recognition of Baptists in North America.” He also said, “It’s the most significant Baptist meeting in my life, after playing in the Baptist yard 55 years or so.”

President Carter’s vision did not end with the “love-in” at the Georgia World Congress Center. Rather it spawned an organization and numerous efforts that carried forward the new covenant’s spirit and ministry to this day.

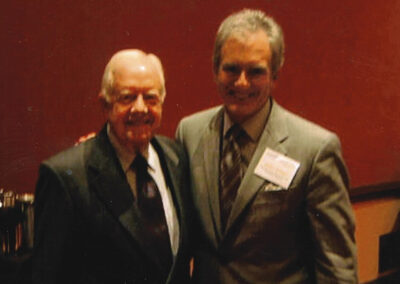

The highlight of my personal interactions on behalf of BJC with President Carter was a wonderful one-on-one meeting with him in his Carter Center office on February 16, 2006. My purpose for seeking the half-hour meeting was first to thank President Carter for his support for religious liberty and BJC over the years. But, specifically, I wanted to ask him to endorse BJC’s capital campaign to finance our proposed Center for Religious Liberty on Capitol Hill. It would be a nerve center for education and training of advocates and serve as BJC’s Capitol Hill offices.

The delightful meeting was an admixture of pleasantries and business. He was friendly and gracious and asked how I was doing at BJC, leading the organization after the legendary James Dunn. He was kind enough to sign and inscribe his new book, Our Endangered Values. (I wish I had brought a baseball for him to sign!) President Carter explained that he could not personally contribute to the capital campaign because his charitable giving (after his church tithe) was committed to go to the Carter Center, but he enthusiastically agreed to endorse both our Center and the campaign.

In his written endorsement, President Carter said, “The Baptist Joint Committee does important work under trying conditions. A Center for Religious Liberty, and a capital campaign to make it possible, is essential to allow the BJC to do its work effectively.”

The necessary funds were raised, and we opened our Center for Religious Liberty on Capitol Hill on October 1, 2012, with remarks by Supreme Court Justice Stephen A. Breyer. The Center continues to thrive as the headquarters of BJC.

Throughout my 28-year tenure at BJC and thereafter as executive director emeritus, when asked what kind of Baptist I am or BJC is, I have usually said, “A Jimmy Carter kind of Baptist.” Those six words saved me 600 almost every time. I’ll continue to say so for the rest of my life — even if God’s grace makes me a centenarian too.

The Rev. J. Brent Walker is executive director emeritus of BJC.

Click here to read a piece by the Rev. Dr. Stan Hastey about his interview with President Carter in 1981.

This article originally appeared in the spring 2025 edition of Report from the Capital. You can view it as a PDF or read a digital flip-through edition.