BJC: Religious freedom is protected by city’s enforcement of nondiscrimination provisions in contracts for foster family certification

Hollman: Faith-based providers do not have a First Amendment right to demand exemption from government contracting requirement that serves the public interest

Media Contact: Cherilyn Crowe / [email protected] / cell: 202.670.5877

WASHINGTON – Today, the U.S. Supreme Court hears arguments in Fulton v. Philadelphia, a case in which a religious organization asserts a free exercise right to apply its religious criteria to discriminate in a government program.

Religious freedom is protected when private organizations performing a government function – such as foster family certification – adhere to nondiscrimination policies, according to BJC (Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty).

BJC and other Christian denominational entities and representatives filed a friend-of-the-court brief in support of Philadelphia. Catholic Social Services is challenging the city of Philadelphia’s rules for agencies that certify foster parents, which says agencies must be willing to work with all qualified adults in this government contract. That means agencies voluntarily partnering with the government to recruit, screen, train and certify foster parents cannot reject prospective foster parents based on religion, sexual orientation or other protected categories.

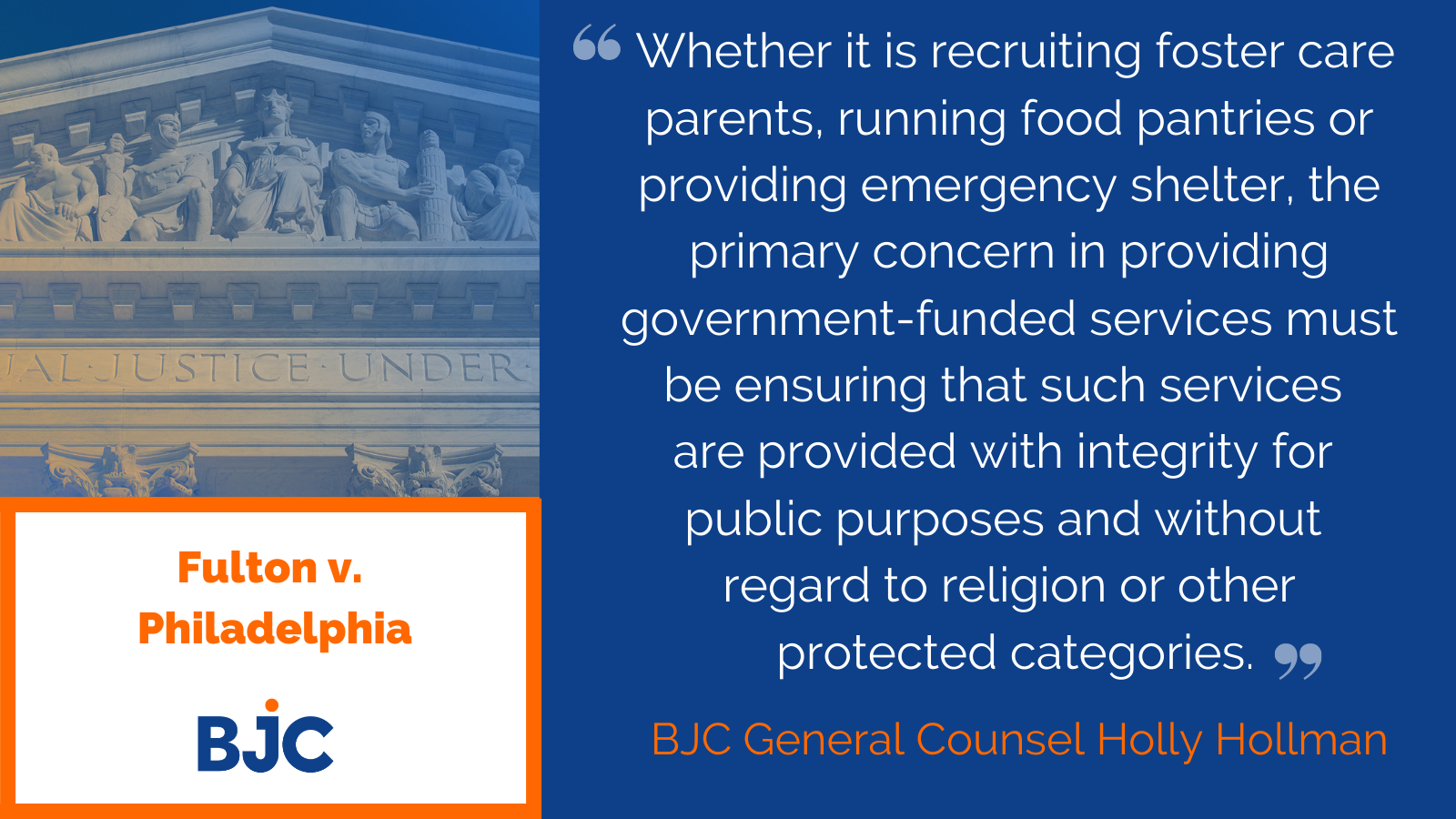

BJC General Counsel Holly Hollman released the following statement today:

“When faith-based groups voluntarily contract with the government to carry out the government’s duty to find safe homes for children in its custody, they must work within the government’s guidelines to ensure qualified families aren’t turned away on the basis of religion, sexual orientation or for other discriminatory reasons. Following the government’s rules to administer government-funded programs does not mean the faith-based organization is giving up its right to speak about core beliefs or criticize government policy in other contexts.

By requiring government-funded foster care agencies to consider all qualified individuals, the city is ensuring that all communities – including religious communities – are treated with equality and dignity. It allows potential foster parents of Jewish, Muslim and other faith traditions the same opportunity to participate in a program as parents from a specific Christian denomination.

Thousands of religious and secular agencies across the country partner with a local, state or federal government to provide government services. Whether it is recruiting foster care parents, running food pantries or providing emergency shelter, the primary concern in providing government-funded services must be ensuring that such services are provided with integrity for public purposes and without regard to religion or other protected categories.”

The Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church, the General Synod of the United Church of Christ, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America joined BJC’s brief.

You can read more about the case and access BJC’s brief at BJConline.org/Fulton.

The Supreme Court is expected to release its decision in Fulton v. Philadelphia by June of 2021.

###

BJC (Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty) is an 84-year-old religiously based organization working to defend faith freedom for all and protect the institutional separation of church and state in the historic Baptist tradition.

FROM BJC’s BRIEF:

“Far from burdening the free exercise of religion, a government’s ability to ensure that those who carry out government functions do so in accordance with that government’s nondiscrimination policy advances the cause of religious liberty.” (p. 4)

“[N]o organization–religious or secular–is entitled to veto the government’s choices on how a public program is to be run. Requiring government contractors to adhere to nondiscrimination policies in their performance of a public function does not burden religion. To the contrary, it protects the integrity of government-funded services and religious freedom. Granting government contractors a constitutional veto over nondiscrimination policies would harm the cause of religious liberty.” (p. 5, emphasis in brief)

“This is not a case about generally applicable laws regulating the general public and in so doing incidentally burdening religious exercise. Rather, it concerns voluntary contracting with a government to perform a public function on its behalf.” (p. 12)

“[T]he City’s nondiscrimination policy reflects not only a valid and compelling interest, but one that advances religious liberty, rather than infringes upon it.” (p. 14, emphasis in brief)

“Religious institutions participating in government-administered social programs like foster care services perform an immensely valuable function. Indeed, the reality of faith-based groups playing such a role in public life is a great strength of our pluralistic society. It is precisely because these services are so important that an entity making a voluntary choice to participate in such a public program is not entitled to displace the government’s nondiscrimination laws and policies in administration of the government’s own program.” (p. 13)

“Hard cases can arise when a government’s important interests must be balanced against substantial burdens on religious exercise. This is not such a case. Here, the City’s nondiscrimination policy reflects not only a valid and compelling interest, but one that advances religious liberty, rather than infringes upon it. Nondiscrimination laws like the Fair Practices Ordinance offer critical protection to religious liberty in a pluralistic society, as do nondiscrimination provisions included in government contracts.” (p. 14)

“The City’s decision to require government-sponsored foster care agencies to consider all qualified parents thus ensures that all communities—including religious communities—are treated by their government with equality and dignity. It also furthers the ultimate purpose of a public program for foster placement: safeguarding the best interests of children within the government’s custody by recruiting the broadest possible pool of qualified foster parents to care for them.” (p. 17-18)

“A prospective foster parent that is rejected for being Baptist, or for being in a same-sex marriage, or another protected characteristic, is likewise a victim of discrimination, whether or not some other agency is willing to consider them. Rejection as a foster parent by an agency carrying out a delegated government function, whether for reasons of sexual orientation or religion, carries with it the sting of public rejection, and at least the implication of state-sanctioned discrimination. These harms are grave and destructive to the human dignity in a pluralistic society.” (p. 18)

“There is no free exercise right to extract a subsidy for religious work in a government program that contravenes the City’s own, democratically determined conception of the public interest.” (p. 21)

“The recipient of the government funding therefore does not give up their right to speak on contrary views—or, as here, to maintain and exercise their religious views—only the right to speak or act on those views through the particular project funded by the government.” (p. 24, emphasis in brief)