By Holly Hollman, BJC General Counsel

At the end of the U.S. Supreme Court’s term, Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement, providing President Donald J. Trump the opportunity to reshape the Court with his nomination of a second justice in just two years, Judge Brett Kavanaugh. With no shortage of issues that divide the country, the prospect of a new justice brought immediate anxiety for some and hopeful anticipation for others.

At the end of the U.S. Supreme Court’s term, Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement, providing President Donald J. Trump the opportunity to reshape the Court with his nomination of a second justice in just two years, Judge Brett Kavanaugh. With no shortage of issues that divide the country, the prospect of a new justice brought immediate anxiety for some and hopeful anticipation for others.

As becomes clearer each day, religious liberty is the responsibility of every American. Legal protections are insufficient without the public’s commitment to uphold it in our pluralistic society. The protection of religious liberty in law and practice is not accidental or self-perpetuating. The separation of church and state is evident in the design of our Constitution, particularly in the ban on religious tests for public office in Article VI and in the first 16 words of the First Amendment: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” It forms the legal basis of our religious liberty and must be vigorously defended.

As the arbiter of these and other laws, the Supreme Court’s role is crucial, and each new justice may have a significant impact. For the BJC, the mark of a good justice is one who takes seriously both Religion Clauses — no establishment and free exercise — as twin pillars of our constitutional architecture, reflecting our country’s unique history and commitment to religious freedom. Though we won’t always agree on the outcome in a given case, we must all demand — as Americans and as historic Baptists — that our courts are nonpartisan protectors of our religious liberty legacy.

As the Senate Judiciary Committee prepares for hearings on the president’s nominee, the BJC is reviewing D.C. Circuit Court Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s record and looking at the potential impact of this nomination on religious liberty and our work. When viewed in light of Justice Kennedy’s church-state legacy and ongoing conflicts, it is clear that living up to our country’s promise of religious liberty for all remains an uphill battle.

Legacy of Justice Kennedy

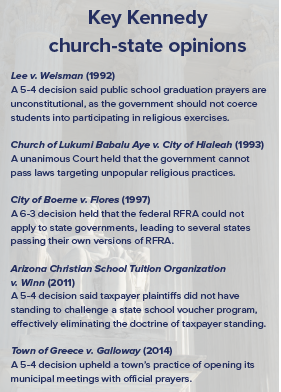

Justice Kennedy’s pivotal role on the Court is undeniable. His record includes casting the deciding vote in landmark decisions across a broad spectrum of legal issues. While his opinions upholding LGBT rights and striking restrictions on abortion access put him at the political center of the nine-member court, his record is complex. He is not known for ideological consistency but instead for being openminded and respectful in the judicial process. Those who have worked closely with him say that he carefully weighs competing values. He maintains civility in disagreement. While those characteristics meant it was possible that Kennedy could be on the side the BJC advocated in any given case, we were often disappointed, particularly in his narrow view of government establishments of religion and when claims may proceed in the courts (known as standing doctrine). When considering his replacement, we acknowledge Kennedy’s extensive religious liberty legacy, important aspects of which are summarized here.

On the free exercise front, Kennedy voted with Justice Antonin Scalia and the majority in Employment Division v. Smith (1990), the case that rejected an exemption for a Native American’s sacramental use of peyote and altered free exercise law. In Smith, the Court held that the Free Exercise Clause does not require exemptions from neutral laws that incidentally burden religion. Opposition to the decision united religious and civil liberty groups, forging a coalition led by the BJC to advocate for the creation and passage of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) to restore the standard Smith undermined. A few years later, Kennedy wrote the majority opinion in City of Boerne v. Flores (1997), which held that the passage of RFRA exceeded congressional authority as applied to the states in violation of federalism principles. That decision meant RFRA no longer applied to state and local governments, and it spurred some states to pass their own versions of that law.

Prior to RFRA’s passage, however, Kennedy wrote the majority opinion for a unanimous Court that found that a law prohibiting the sacrificial killing of animals violated the Free Exercise Clause. Ameliorating the sting of the Court’s ruling in Smith, Justice Kennedy’s opinion in Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye v. City of Hialeah (1993) at least made clear that the Constitution still forbids the government from unfairly targeting religious practices. That case has been cited broadly and creatively in recent cases, such as Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia v. Comer (2017), which challenged a state’s rule designed to avoid funding places of worship, and Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission (2018), which challenged government efforts to ensure LGBT nondiscrimination in the commercial marketplace.

Kennedy joined unanimous decisions to uphold strong statutory protections for free exercise provided by the passage of RFRA and the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA). In the most controversial application of RFRA, Kennedy cast the deciding vote in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores (2014). That case upheld RFRA’s application to a closely held for-profit corporation and found that the retail chain was entitled to relief from a requirement to provide contraceptive coverage to its employees. While the scope of the Court’s ruling is contested, Kennedy’s narrow concurrence emphasizes the Court’s assumption that the government has a compelling interest in women’s health and equality. He stressed the importance of providing an accommodation for the employer that would not risk loss of benefits for employees.

Like other conservative justices, Kennedy has been less likely to find violations of the Establishment Clause, which protects religious freedom by keeping government from advancing, sponsoring or affiliating itself with religion. Establishment Clause cases include government involvement in religious displays and funding for religious institutions or religious exercises. While noting that this area of the law is fact-sensitive, Kennedy consistently voted to uphold religious displays on government property. He explicitly rejected the endorsement test, which would strike government actions that send the message that those who agree with a religious message are political insiders. Instead, Kennedy more often focused on whether the government coerces support for or participation in religion, or otherwise acts in a way that establishes religious faith or tends to do so.

Kennedy was more concerned about government advancement of religion in the public schools where he found government coercion more readily apparent. His majority opinion in Lee v. Weisman (1992) found school-sponsored prayers at graduation ceremonies to be unconstitutional, and he voted to strike a school policy providing for student-led prayer at public high school football games in Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe (2000). In Lee, he explains the different ways that speech and religion are protected in the First Amendment. He recognizes that it protects objectors and dissenting non-believers, but it also exists to protect religion from government interference.

Kennedy expressed less concern with government-sponsored religion in Town of Greece v. Galloway (2014), a case in which he wrote the majority opinion in a 5-4 decision upholding a prayer practice (predominantly Christian prayer) at local government meetings. While purporting not to announce a new test or extend beyond cases that deal with “ceremonial” prayer, the decision is noteworthy for its broad reading of Marsh v. Chambers (1983), which upheld chaplain-led prayer before state legislatures, citing historical practices in Congress. In the BJC’s brief, which was cited in a dissenting opinion, we argued that Marsh should not have been extended to the context of local government meetings where citizens gather to conduct civic business. Though the settings have material differences, Kennedy and the majority were unwilling to distinguish the Town of Greece’s practice from the prayers upheld in Marsh.

Kennedy’s final opinions

Kennedy wrote separately in both religious freedom cases before the Court this term. While neither opinion breaks new ground nor provides much guidance, both reflect his measured style and focus on dignity.

Justice Kennedy’s legacy advancing equality for LGBT people is well established. As conflicts between marriage rights and religious objections rose through the courts, advocates on all sides focused on Kennedy, who is also a staunch free speech advocate. Not surprisingly, he wrote the majority opinion in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission (2018), a case in which a commercial baker refused to prepare a custom cake for a same-sex couple in violation of a state statute that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, among other protected categories. Kennedy’s opinion for a 7-2 majority rests on the perceived animus in the administrative proceedings that originally decided against the baker. It was not a broad win for religious objectors to LGBT rights, and it instead reflects a commitment to LGBT equality and the struggle to uphold the dignity of those who oppose same-sex marriage on religious grounds.

Kennedy provided his last religious liberty statements as a sitting justice in Trump v. Hawaii (2018), a 5-4 decision upholding the third iteration of a Trump administration immigration and refugee policy that began with Trump’s promise of a Muslim ban. He joined Chief Justice John Roberts’ majority opinion in full and wrote a short concurrence. While the majority opinion gave short shrift to the religious animus concerns, Kennedy highlighted the pressing danger to the Constitution inherent in executive discretion free from judicial scrutiny:

“The First Amendment prohibits the establishment of religion and promises the free exercise of religion. From these safeguards, and from the guarantee of freedom of speech, it follows there is freedom of belief and expression. It is an urgent necessity that officials adhere to these constitutional guarantees and mandates in all their actions, even in the sphere of foreign affairs. An anxious world must know that our Government remains committed always to the liberties the Constitution seeks to preserve and protect, so that freedom extends outward, and lasts.”

With these words calling for government officials to be accountable to our constitutional ideals, Kennedy exits and provides an opening for a justice whose approach appears to be quite different from his own and less concerned about deferring to the executive branch.

Judge Brett Kavanaugh

Kavanaugh grew up in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., and is well-known in the D.C. legal community where he has spent most of his professional life, following his education at Yale. At the announcement of his nomination, he mentioned that he, like Kennedy, is Catholic.

He spoke of his community activism, particularly through his church and church-related charities, which suggests he would affirm religion’s vibrant role in the public square. From that, some may assume he would sympathize with claims asserted by religious individuals and institutions and be a strong protector of religious liberty. Being a faithful religious adherent, however, is not synonymous with upholding the Constitution’s promise of religious liberty for all and guarding against government advancement of or interference in religion.

As a former Kennedy clerk, Kavanaugh claims great admiration for the justice whose seat he hopes to take. On a variety of issues, however, Kavanaugh’s record suggests he will shift the Court in a decidedly different, more ideological direction. His government service is extensive, including 12 years as a judge on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals and as a lawyer in the executive branch. His experience provides abundant material for the Senate to review and form an opinion about his ability, judicial temperament and approach to a number of important legal issues. Compared to other areas of law that are more commonly brought before the D.C. Circuit (such as regulatory issues), Kavanaugh’s church-state record is sparse. Still, it is fair to say that religious freedom is an issue of personal and professional interest to him.

The Kavanaugh record

While serving on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, Kavanaugh participated in at least a dozen cases that addressed church-state issues. The few in which he wrote opinions, as well as his public speeches, give the most significant clues about his views and how he may differ from the justice he hopes to replace.

His admiration for Justice Kennedy’s approach is on display in a number of cases. For instance, Kavanaugh narrowly construes standing, though his views in various cases are difficult to reconcile. One case challenging prayers and religious references at inaugurations was dismissed for lack of standing, but he wrote a concurrence to explain that he would have found standing and rejected the claim on the merits. In doing so, Kavanaugh dismissed the idea that the incidents were minor or lacking religious importance and explained his view that they were nonetheless consistent with American history and tradition and the Court’s ruling on legislative prayers with Marsh.

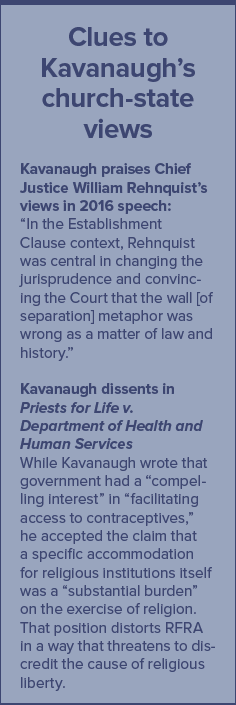

In a dissent from the D.C. Circuit’s decision in Priests for Life v. Department of Health and Human Services (2014), one of many challenges to the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate, Kennedy’s influence on Kavanaugh seems apparent. Kavanaugh noted that the government had a “compelling interest” in “facilitating access to contraceptives,” a position criticized by some D.C. Circuit, however, Kavanaugh accepted the plaintiffs’ claim that the accommodation provided for the plaintiffs (which the Supreme Court had relied on in Hobby Lobby) was itself a “substantial burden” on the exercise of religion under RFRA. That issue was heard but later dismissed by the Supreme Court without decision in Zubik v. Burwell (2016). In a brief filed in the Zubik case, the BJC argued that the plaintiffs’ position amounts to near total deference and is dangerous to RFRA’s continuing vitality and the whole enterprise of religious exemptions.

Perhaps more telling than these opinions is Kavanaugh’s praise for the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s influence on church-state matters. In a recent speech, Kavanaugh credited Rehnquist for moving away from church-state separation toward non-preferentialism with regard to religious institutions seeking government funding. The distinct roles of the institutions of religion and government have guaranteed the flourishing of religious liberty and protected religious institutions from government interference. But Kavanaugh’s comments raise alarms that he lacks appreciation for the unique treatment of religious institutions in our constitutional history.

Looking to the future

The Supreme Court’s precedents acknowledge that the institutional separation of church and state is beneficial to religious liberty. From Ke nnedy’s legacy, it is evident in Lee v. Weisman and, to a lesser extent, in the boundaries he outlined in Greece v. Galloway. His emphasis on dignity and his view of the harm that may be inflicted by government coercion in religious matters provided some measure of protection against majoritarian abuses. Whether Kavanaugh appreciates the Establishment Clause as a limit on government involvement with religion and an essential protection for individual religious liberty is questionable.

nnedy’s legacy, it is evident in Lee v. Weisman and, to a lesser extent, in the boundaries he outlined in Greece v. Galloway. His emphasis on dignity and his view of the harm that may be inflicted by government coercion in religious matters provided some measure of protection against majoritarian abuses. Whether Kavanaugh appreciates the Establishment Clause as a limit on government involvement with religion and an essential protection for individual religious liberty is questionable.

As the Senate hearings commence, the BJC expects a careful examination of the nominee and his approach to religious liberty. Acknowledging the vital role of religion in the life of the country is essential, and our Constitution embraces a welcoming role of religion in the public square. That role is protected by Free Exercise and Establishment Clause principles, including those that prevent government sponsorship of religion, whether through government-led religious practices or funding schemes. Like the Founders recognized, government should refrain from usurping religion’s role, and the courts must uphold that vision protecting religious liberty for all.

This article appeared in the July/August 2018 edition of Report from the Capital. You can also read the digital version of the magazine or view it as a PDF.