As Baptists, we claim a long legacy of women and men who have risked their lives to advocate bravely for religious liberty for all.

BJC (Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty) continues this legacy of defending the right of everyone to choose a faith journey free from government coercion or penalty, while leading honest and open conversations about our past failings and how we can forge a more inclusive future.

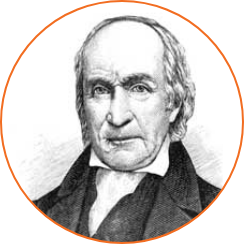

The Founder

In 1612, Thomas Helwys, one of the founders of the Baptist movement, published the first treatise in the English language calling for religious freedom, A Short Declaration of the Mystery of Iniquity. “For men’s religion to God is between God and themselves. The king shall not answer for it,” he wrote. “Let them be heretics, Turks [Muslims], Jews, or whatsoever, it appertains not to the earthly power to punish them in the least measure.” It was a dangerous view under the rule of King James I; Helwys was sent to Newgate Prison for his advocacy of religious tolerance. He died there in 1616.

The Rebel

The Pioneer

In 1631, Roger Williams arrived in the Massachusetts Bay colony, having left England to escape religious persecution, but he encountered it on these shores, too. Preaching “soul freedom,” the notion that faith could not be dictated by any government authority, he was banished from the colony for heresy. He went on to establish the colony of Rhode Island, setting up its government as a “lively experiment” to protect “liberty of conscience.” He also helped create the first Baptist congregation in colonial America in 1638, and he was the visionary who introduced the language of a “wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world.”

The Persecuted

The Lobbyist

The Organizer

Since the days of slavery, African-Americans have fought to worship God freely: first in secret and then through small plantation churches under the master’s watch. Preacher Gowan Pamphlet began his ministry as an enslaved person in Williamsburg, Virginia, in the 1770s. Pamphlet bravely evangelized at a time when slave religion, often associated with rebellion, was violently quashed by those in power. Despite threats and attacks, Pamphlet persevered, and grew his congregation to around 500 people. When he was set free in 1793, he applied for, and was received into, membership of the Dover Baptist Association. He pastored the only Baptist church in Williamsburg until his death in 1807. The church continues to this day as the First Baptist Church of Williamsburg.

The Abolitionist

The Leader of the Movement

Baptist preacher and Nobel Prize laureate Martin Luther King, Jr., proclaimed that religious liberty was crucial to enabling the civil rights movement. “The church must be reminded that it is not the master or the servant of the state, but rather the conscience of the state,” he said in Strength to Love. King paid dearly for this activism: he was arrested more than 20 times, his home was bombed, and he was assassinated at only 39 years old. But his words have not been silenced. In his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963 from the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., King declared to the 25,000 marchers that he envisioned the “day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!'”

The Firebrand Activist