By Executive Director J. Brent Walker

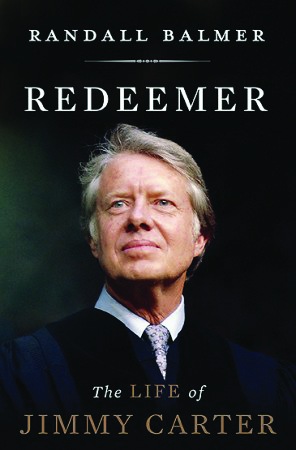

Adopting the Christian motif of redemption, Randall Balmer has penned a new biography titled Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter. Balmer is a professor at Dartmouth College, an Episcopal priest and the BJC’s 2009 Shurden Lecturer. Balmer tells the story of Jimmy Carter’s political life, drawing a parallel between the gospel’s redemption narrative and “Carter’s transformation from the ashes of political annihilation in 1980 to elder statesman, world-renowned humanitarian, and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize.”

Adopting the Christian motif of redemption, Randall Balmer has penned a new biography titled Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter. Balmer is a professor at Dartmouth College, an Episcopal priest and the BJC’s 2009 Shurden Lecturer. Balmer tells the story of Jimmy Carter’s political life, drawing a parallel between the gospel’s redemption narrative and “Carter’s transformation from the ashes of political annihilation in 1980 to elder statesman, world-renowned humanitarian, and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize.”

According to Balmer, redemption can be discerned on at least two levels. First, Carter’s election to the presidency in 1976 reestablished the political viability of progressive evangelicalism that had lain dormant for decades. In a way that had not been seen in a national campaign at least since William Jennings Bryan ran for president at the turn of the 20th century, Carter spoke freely and naturally in his campaign about his “born again” faith. Balmer tells the story of how Carter — only a decade and a half after John F. Kennedy had urged the country to put his Catholicism aside in their voting calculus — unapologetically highlighted his evangelical faith to corroborate a progressive public policy agenda.

Carter’s public expression of his religious faith was tempered by his Southern Baptist-rooted appreciation for the separation of church and state. Indeed, in his famous (or to some, infamous) interview in Playboy magazine — more renowned for Carter’s confession of having “committed adultery in [his] heart” — Carter declared, in Kennedyesque fashion, his “belief in absolute and total separation of church and state.” As Carter himself has pointed out in his own book, Our Endangered Values, although personally opposing abortion and capital punishment, as president he was able to enforce the civil law with respect to those issues.

Balmer chronicles Carter’s four years as president and describes how millions of evangelicals who had cheerfully supported Carter in 1976 turned against him in 1980, voted for Ronald Reagan and helped usher in a new brand of conservative evangelical politics that would eclipse the progressive evangelical tradition throughout the 1980s and beyond.

If Carter’s redemption of progressive evangelicalism’s political expression failed or was only transitory, Balmer  describes a second redemption that is more substantial and lasting. It has often been said that Carter was “the first president to use the White House as a stepping stone.” However historians ultimately judge Carter’s presidency, they will certainly report that he was one of the best former presidents in our history. Carter’s commitment to a variety of social issues — including fair housing through Habitat for Humanity, the elimination of poverty around the world through the work of the Carter Center and his never-ending labor for peace in the Middle East — has elevated him to a citizen of the world and merited the Nobel Peace Prize. Balmer also chronicles how Carter became the public face of moderate Baptist life after his repudiation of Southern Baptist fundamentalism, his embrace of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, his efforts to make peace among the warring factions of Southern Baptist life and his outreach to Baptists of many stripes through the New Baptist Covenant initiative over the past several years.

describes a second redemption that is more substantial and lasting. It has often been said that Carter was “the first president to use the White House as a stepping stone.” However historians ultimately judge Carter’s presidency, they will certainly report that he was one of the best former presidents in our history. Carter’s commitment to a variety of social issues — including fair housing through Habitat for Humanity, the elimination of poverty around the world through the work of the Carter Center and his never-ending labor for peace in the Middle East — has elevated him to a citizen of the world and merited the Nobel Peace Prize. Balmer also chronicles how Carter became the public face of moderate Baptist life after his repudiation of Southern Baptist fundamentalism, his embrace of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, his efforts to make peace among the warring factions of Southern Baptist life and his outreach to Baptists of many stripes through the New Baptist Covenant initiative over the past several years.

The resurrection of progressive evangelicalism and the continuing redemption seen in Carter’s post-presidential life are accompanied in this book by other subtexts. These include Carter’s upbringing in rural Georgia, his life in the Navy, his marriage to Rosalynn and, in Balmer’s words, his “insatiable ambition to rise above his circumstances.” The book’s epilogue recounts the author’s “Sunday Morning in Plains,” visiting the Sunday school class that Carter teaches and enjoying time with the Carters after Maranatha Baptist Church’s worship service was over. Balmer also includes two substantial appendices — one, a timeline of Jimmy Carter’s life and the other, the full text of Carter’s “Crisis of Confidence” speech, often mistakenly referred to as the “malaise” speech (the word malaise was never used!). Often regarded as a watershed event in his presidency, the speech — sounding for all the world like a sermon — reflects Carter’s political passion, as well as his determination to succeed and frustration in falling short as he laments “the loss of unity of purpose for our nation” and calls for “the restoration of American values.”

The association of a theological concept like redemption with a biography of a president can be tricky at best and sacrilegious at worst. Balmer acknowledges this and avers that Carter would never make any messianic claims for himself. That disclaimer made, the parallels that Balmer draws are not hard to see. Perhaps “Redemption,” rather than “Redeemer,” would have been a better title. But anyone who is interested in squaring appropriate expressions of faith in politics along with the separation of church and state, 20th century American political and religious history, and Baptist life in this country over the past four decades will want to read and savor this important and incisive effort by Randall Balmer.

From the June 2014 Report from the Capital. Click here for the next article.