NEW PODCAST on the 30th anniversary of RFRA: Click here to listen as Amanda Tyler and Holly Hollman discuss the origins of RFRA and how it’s been used over the past three decades.

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act

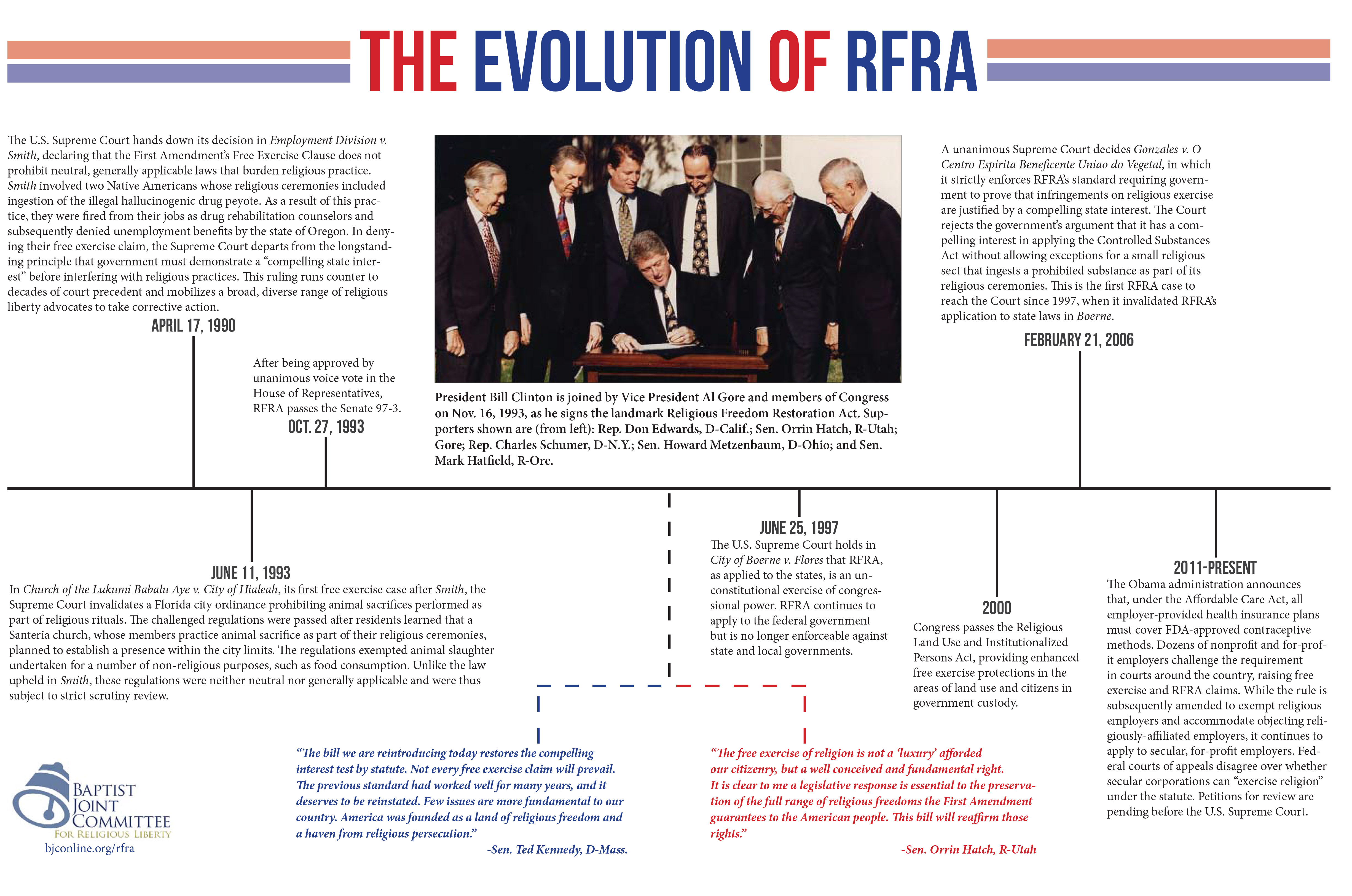

President Bill Clinton signs RFRA into law in 1993. BJC Photo

In 1993, a broad and diverse coalition of religious liberty advocates welcomed passage of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), a law that resulted from several years of hard work and reflected a shared commitment to protecting the free exercise of religion in America. RFRA created a statutory right that would apply broadly to ensure that government did not substantially burden the exercise of religion without a compelling reason for doing so.

Two decades later, opinions on RFRA vary. Some prior RFRA advocates now express concerns about its application in particular contexts, such as its interaction with civil rights and health care laws; others argue RFRA has not lived up to its promise of providing meaningful protection for religious liberty for all people. Others conclude that RFRA, while not perfectly applied in every case, has on balance provided meaningful protection against governmental interference with the exercise of religon.

Story of RFRA

The story of RFRA began in 1990, when the U.S. Supreme Court shocked many religious and civil liberty advocates by announcing in Employment Division v. Smith that the First Amendment is not violated when neutral, generally applicable laws conflict with religious practices. The new standard generated widespread concern that it threatened minority and mainstream religious groups alike, leaving them vulnerable to potentially onerous government burdens on religion. View a timeline of RFRA

In response, an extraordinary coalition of organizations — chaired by the Baptist Joint Committee — coalesced to push for federal legislation that would “restore” the pre-Smith compelling interest standard. Their bill became law when President Bill Clinton signed RFRA on November 16, 1993. Because the Supreme Court later held that RFRA was unconstitutional as applied to the states, many states have enacted similar legislation to constrain state government actions.

Coalition members recognized at the time that RFRA provided a high standard for all free exercise claims without regard to any particular religious practice or desired outcome, and that it would produce different results according to the facts of individual disputes. Still, common ground lay in the belief that all Americans have a right to exercise their religion.

For more on RFRA:

Visit our page dedicated to a symposium marking the 20th anniversary of RFRA, including panel discussions on its beginnings, application to the contraceptive mandate, and future challenges to the exercise of religion in a diverse society.

RFRA and the contraceptive mandate:

BJC General Counsel Holly Hollman: Examining RFRA in light of Hobby Lobby

BJC Executive Director Brent Walker: Exploring Hobby Lobby’s narrow victory

Walker: RFRA’s constitutionality called into question

Hollman: BJC supports strong legal standard in contraceptive cases

Additional resources

BJC’s Brent Walker remembers the origins of RFRA.

BJC General Counsel Holly Hollman examines RFRA on its 20th anniversary.

Walker’s primer on the governmental accommodation of religion in the Journal of Church and State (2007).

Hollman reviews the impact of the Supreme Court’s 2006 decision bolstering RFRA (O Centro Espirita Beneficiente Uniao Do Vegetal v. Gonzales)