S4, Ep. 20: The Ten Commandments

Texas is taking matters into its own hands, going full-on cowboy as it leads the nation in abandoning long-held religious liberty protections. Amanda and Holly review a troubling bill in Texas that would mandate the posting of the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms, and they share how some are trying to use the Kennedy v. Bremerton decision – and removal of the Lemon test – to justify this effort. They also review some surprising moments during a Texas Senate hearing on the bill, including when Baptists discover they have different understandings of their own theology. In the final segment, Amanda and Holly review the religious freedom problem with legislation like this and share ideas for engaging in conversation that can help reframe the issue.

SHOW NOTES:

Segment 1 (starting at 00:41): Dueling over the Ten Commandments

Amanda and Holly discuss last year’s Supreme Court decision in Kennedy v. Bremerton on episode 21 of season 3.

Amanda and Holly talk about the Lemon test, from the 1971 decision in Lemon v. Kurtzman. They also mention the 1980 Stone v. Graham decision.

The proposal in Texas is Senate Bill 1515, and the text is available online.

Amanda and Holly mentioned this piece by Britt Luby for Baptist News Global: ‘Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife’ and other posters I do not want in a first grade classroom.

Read Amanda’s Tweet about this proposal in Texas.

Segment 2 (starting at 13:28): The Texas Senate hearing on this bill

You can listen to the Texas state Senate hearing on Senate Bill 1515 at this link. We played a clip of Tara Beulah, which appears at 27:13 in that video.

Former BJC Executive Director Brent Walker wrote this piece in 2005 debunking some of David Barton’s claims.

You can find resources on Christian nationalism on the website of our Christians Against Christian Nationalism campaign.

Segment 3 (starting at 30:01): Engaging in conversation about the Ten Commandments

In 2005, the two Supreme Court cases dealing with the posting of the Ten Commandments in government settings were McCreary County v. ACLU and Van Orden v. Perry.

Read Holly’s preview column, which included ways to engage in conversation about the issue, on page 6 of this magazine: Supreme Court’s review of Ten Commandments cases an opportunity for education on religious liberty

After the cases concluded in 2005, Holly wrote this column: Making sense of the Ten Commandments cases

For more resources from BJC on religious displays, visit BJConline.org/religious-displays.

The Respecting Religion podcast was honored with two DeRose-Hinkhouse Awards from the Religion Communicators Council: Best in category for an individual episode, recognizing our episode on the Kennedy v. Bremerton decision, and an award of merit for season 4 of the podcast.

Respecting Religion is made possible by BJC’s generous donors. You can support these conversations with a gift to BJC.

Transcript: Season 4, Episode 20: The Ten Commandments (some parts of this transcript have been edited for clarity)

Segment 1: Dueling over the Ten Commandments (starting at 00:41)

AMANDA: Welcome to Respecting Religion, a BJC podcast series where we look at religion, the law, and what’s at stake for faith freedom today. I’m Amanda Tyler, executive director of BJC.

HOLLY: And I’m general counsel Holly Hollman. Today we’re going to talk about a specific legal development arising out of the Supreme Court’s shift in religious liberty law. It’s a legislative effort requiring the posting of the Ten Commandments in every public school classroom in Texas.

AMANDA: That’s a lot of public school classrooms, Holly.

HOLLY: It is. So this follows a change in Supreme Court precedents about how the Court interprets the No Establishment Clause, and for those who want to go back and understand a little bit more what happened, you could listen to our episode 21 of season 3 — last season — where we talked about the case Kennedy v. Bremerton.

Actually, it’s one of our most popular episodes. We taped it live in front of an audience right after the Supreme Court decided that decision, and we really unpacked what the Court said, what they did, and what they didn’t do, which is very important for our conversation today.

Of course, that decision was about a teacher, specifically a football coach, and the Court upheld his right to pray at a school event, specifically on the 50-yard line. There was a lot of confusion about the facts and the precise holding, so you can go back and listen to that or you can see on our website more information about that case.

Of course, we at Respecting Religion know that teachers and students have religious freedom rights in the public schools, but of course, teachers and students aren’t in the same positions, so the rules shouldn’t be the same, and we don’t think teachers should pray on the 50-yard line while on duty or in other ways that seem likely to coerce students or involve the school in religious exercises.

And we don’t believe the Kennedy v. Bremerton case gives schools the authority to lead religious exercises with students. That was an important part of that decision — in the end, when they upheld Coach Kennedy’s right, he was not praying with the students at the time.

An important part of that decision that affects our conversation today is that the Court abandoned what is known as the Lemon test. It’s named after a case in the 1970s called Lemon v. Kurtzman, and the Lemon test is just one of several tests that the Supreme Court has used to try to understand and define, what does it mean to have an establishment of religion, the First Amendment saying that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

And, of course, the First Amendment applies to states and to local governments, including public schools. So in the Kennedy case, the Court abandoned this Lemon test, and we’re not going to use that anymore. But unfortunately, the Court did not leave a lot of instruction for lower courts.

AMANDA: That’s right. And we knew when we got that rather vague decision that took away one test but didn’t replace it with anything else in particular, that there would be struggles and confusion in the lower courts. You, Holly, are following those cases, and I’m sure at some point on Respecting Religion we will talk about the impact of that decision and what it looks like for government-sponsored religious exercise in public schools.

HOLLY: The Court said that instead of Lemon, courts should look to history and tradition but didn’t really give guidance about what that means. And, of course, history plays a big part in Establishment and Free Exercise law, because, as everyone knows — as everyone’s taught about our religious freedom country that we live in — that part of the reason that people came to this country was for religious freedom, so that’s part of our history.

So the Court abandoned that test — famous for its three prongs or later two prongs — that requires a secular purpose and make sure that you don’t have a predominant effect of advancing religion or entangling religion and government in different ways. The Court said, we’re not going to look at that test anymore or even other tests related to that; instead we’ll just look to history.

And we knew ‑‑ as you said, Amanda, we knew that there would be problems, and it’s going to take a while to see how lower courts shake out, what does it mean to violate the Establishment Clause; what are other tests that the courts can look to that still exist; and what, if anything, remains kind of in the background of Lemon, if not the test itself.

AMANDA: Meanwhile, in Texas, the legislature is just going full-on cowboy. They have just decided that they don’t need to wait around to see how these courts figure out the history test. They are going to go right after any case from the past that relied on the Lemon test and say that that’s no longer good law, and then just try to do the bad idea again and see if they have better luck with this Supreme Court, without the Lemon test in place.

HOLLY: They literally say ‑‑ I’ve seen advocates literally say, “Lemon is gone; liberty is back.” It’s amazing.

AMANDA: Yeah. As if the only reason we wouldn’t want to have things like the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms is because of some legal test, that there weren’t other reasons that that was a bad policy choice.

Well, speaking of bad policy choices, Texas is not the first one to have this idea. The Kentucky legislature had passed a law in the 1970s that required the posting of the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms, and that law was challenged, and in 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down that law as unconstitutional in a case called Stone v. Graham. And that case relied on the Lemon test in finding that the posting of the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms would violate the No Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

HOLLY: And particularly, they said that there was absolutely no secular purpose for putting sacred Scripture in every classroom. Imagine every classroom. You look around. There’s typically bulletin boards about the lessons. There’s probably a flag, about, you know, respect for the country, and a chalkboard and things. And, like, why are the Ten Commandments in every classroom?

And it was clear — and the Court made clear in that case that there was no secular reason, that it was only a hopeful reason that children would look and read scripture and meditate on the Ten Commandments. And that case was decided in a per curiam decision, and it’s not one that I often hear people talking about being problematic. I mean, clearly that would be the promotion of explicitly religious activity, selective religious activity ‑‑

AMANDA: That’s right.

HOLLY: — in a compulsory school setting.

AMANDA: And without any kind of comment on why it’s there.

HOLLY: Right. Context to understand it.

AMANDA: Exactly. But Texas didn’t seem to learn that lesson, so we have Senate Bill 1515 that is pending now in the Texas House but has been passed by the Texas Senate. And so we want to describe a little bit about what Senate Bill 1515 does and some of the legislative action we have seen there and talk about it as a very problematic development in religious liberty law.

HOLLY: Pretty straightforward. What does the bill say, Amanda?

AMANDA: Well, the bill says ‑‑ it’s a very short bill, two-and-a-half pages of legislative text ‑‑ that, “A public elementary or secondary school shall display” ‑‑ so requirement ‑‑ “in a conspicuous place in each classroom of the school a durable poster or framed copy of the Ten Commandments that meets the following requirements.”

And the following requirements are very specific, Holly. The framed copy has to be in a “size and typeface that is legible to a person with average vision from anywhere in the classroom in which the poster or framed copy is displayed.”

HOLLY: So it can double as an eye test for the kids maybe.

AMANDA: Well, that could be the secular purpose. Right? So they say in the bill that that size would be at least 16 inches wide and 20 inches tall. And then they say exactly what the text of the Ten Commandments should be.

HOLLY: And, Amanda, that’s ‑‑ of course they have to say what it is, because you can’t just say, “Post the Ten Commandments,” because as people who are familiar with Scripture know, the Ten Commandments is just basically a shorthand way that people refer to certain Scripture, particularly the laws of Moses that appear in two different books of the Bible and are translated in many different versions.

And, you know, we really don’t have time to talk about all the historical and theological debates that would inform one’s understanding of the Ten Commandments here. And yet — and yet — the Texas legislature is putting forth a bill to post the Ten Commandments. And so what do they say? What are the Ten Commandments in this Texas proposal?

AMANDA: So from the legislative text, it starts, “The Ten Commandments. I AM the LORD thy God.” I’m not going to read the whole thing. But I’ll read some of them.

“Thou shalt have no other gods before me. Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy.” And then farther down, “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s house. Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his cattle, nor anything that is thy neighbor’s.”

That gives you a flavor for what every public school classroom in Texas could have posted come next school year.

HOLLY: Yeah. It’s probably not the way many Texas families who attend Christian churches are used to hearing the Ten Commandments. So am I right to say this is the King James version or at least some kind of adaptation of that?

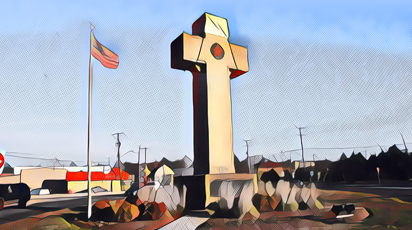

AMANDA: Well, it certainly sounds like the King James version with all the “thy”s and “thou”s and “sayeth”s. This version of the Ten Commandments is an adaptation of the King James version, and it is identical to the language that is on a large stone monument on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol.

And as some of our listeners might recall, the constitutionality of that monument went up to the Supreme Court and was upheld in a case from 2005, but of course, the context here is completely different than it is with this poster that would be put in every public school classroom in Texas.

HOLLY: Yeah. We can come back to that, about the Establishment Clause standards and religion in public life. And, you know, we know a lot about that, and we were, of course, involved in those cases, the Ten Commandments cases back in 2005. But this is something distinct. The context in that 5-4 decision is quite different from this context.

And, you know, Amanda, as you were reading that text, it reminded me of that smart piece that one of the BJC Fellows wrote after she learned about this bill, and the headline said, “‘Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife’ and other posters I do not want in a first-grade classroom.”

AMANDA: We will link to Britt Luby’s piece for Baptist News Global in the show notes for this episode. And besides having a witty title, it really has some excellent arguments from this BJC Fellow who is also a mother of a public school student in Texas about why she, as a faithful Catholic and as someone who is concerned about religious freedom, is also very concerned about this bill.

HOLLY: Yeah. So it hasn’t gotten a lot of attention so far, because, as you noted, it’s still in process in front of the Texas legislature. But it certainly got our attention as a particularly bad idea and brazen attempt by a legislature to push forward a religious agenda as soon as they had a crack in the Court’s Establishment Clause jurisprudence.

You know, they’re going to go push ahead full force. And so we are interested in seeing, you know, what does this look like in Texas. How are people talking about it, where did this come from, who’s behind it, and we wanted to really look at it a little more closely.

So in addition to making a quick statement to say, as you did on Twitter, Amanda, “Forcing public schools to display the Ten Commandments violates religious liberty.” Just note. Everyone pay attention. “The government should not be in the position of making religious decisions.” And we as Baptists “reject this effort because of our theological convictions” as well as our commitment to religious liberty.

You know, we had to take a stand against it, but we wanted to look more closely at how this came up in Texas and what it looked like to have a hearing on the bill.

Segment 2: The Texas Senate hearing on this bill (starting at 13:28)

AMANDA: And so, Holly, you and I watched, at least ‑‑

HOLLY: So you don’t have to.

AMANDA: — parts of this incredibly troubling Senate hearing. It was a Senate committee on education in the Texas Senate, and first up was Senator King, who is the bill’s sponsor for this bill, Senate Bill 1515, and he explicitly linked the changes in Supreme Court law with the abandonment of the Lemon test to the rationale for bringing this bill up at this point.

He also said that it was important as a recognition of religious heritage, which are buzz words for us that signal that this is part of a larger agenda of pushing Christian nationalism in the public schools.

HOLLY: And unbelievably that he thinks this is an act of religious liberty. I mean, putting aside that there’s a change in Supreme Court approach ‑‑ and we could talk about that forever, you know, how the Court interprets the First Amendment.

But to so boldly say that this is an advancement of religious liberty for the government itself to pick and choose a religious text and put it in every school classroom just shows you how much work we have to do to really affirm our country’s approach to religious freedom and how it protects all people, without regard to religion, and keeps the government out of the business of being responsible for religion.

AMANDA: And I think that language of trying to use “religious freedom” to defend the bill is particularly galling to us, Holly, because we see this much more as an effort to privilege a certain religious perspective and in this point, a certain religious translation, abridged, of a religious text by the government. This smacks of Christian nationalism, and then to use the words of “religious freedom” to defend it is quite infuriating.

HOLLY: Well, the first panel of witnesses included some lawyer and history types. First of all, a lawyer from First Liberty Institute — and they are very prominent in litigation, and in fact, represented Coach Kennedy in this recent case. So hearing that, it was just so obvious that they have been pushing to move the law of religious liberty in a way that would allow much more government involvement in religion, much more religion in the public schools, in a way that has typically been found to violate the Establishment Clause.

Particularly Matt Krause of First Liberty said that Kennedy did to religious liberty what Dobbs did to abortion, really arguing a pretty extreme position that any decisions based on Lemon are no longer good law. And let me just say right here that the Court did abandon the Lemon test, but it did not reverse the Lemon decision.

Lemon dealt with specific legislation that, in fact, advanced religion in the public schools, and the Court found it unconstitutional. It had to do with direct aid to religion, and that case was not reversed, and there’s a lot of questions that remain after the Court has abandoned the Lemon test about exactly what the relationship is between religion and government, particularly aid in public schools.

But Matt Krause was pretty clear. We’re pushing this agenda. We won for Coach Kennedy, and now we’re pushing forward to make sure that we get the Ten Commandments in every classroom, and, you know, feeling quite confident, given their recent success at the Court, that this is constitutional. Again, I would call this a really bold, brazen act by the Texas legislature. But this first panel is saying, go for it; you got it. We’re here for you; we’ll back you up.

AMANDA: And I think Matt Krause was reading the room really well, because there’s nothing Texans like more ‑‑ and I can say this myself as a Texan — there’s nothing Texans like more than to say that they’re the best and they’re the first at something.

HOLLY: Yeah.

AMANDA: And so he’s saying, Look, legislature, you can be an example for the rest of the country; you should pass this, and then we’ll be able to have these kinds of provisions for the rest of the country as well.

And, you know, I did think it was interesting — though they’re arguing this really extreme position that abandoning the Lemon test means overturning every decision that the Supreme Court ever made that used the Lemon test to come to their decision — that they still seem to be arguing implicitly that they had a secular purpose for this bill.

They were trying to make an argument that this wasn’t a religious law, that instead that the reason was because the Ten Commandments was the basis for American law and for Texas law, they said in particular, and that it would be important to the education of Texas schoolchildren to understand how the Ten Commandments were a basis for the law.

Now, nothing in the legislation explains that that would be put on the poster in any way. The poster would just be the Ten Commandments without any kind of explanation.

HOLLY: Well, that’s more bad education anyway.

AMANDA: Right. But to bear this out, they brought in David Barton who is very familiar to us as the chief propagator of the “Christian nation” mythology and with his pseudo-history and his cherry-picked history of Founders’ quotes, and he is a frequent speaker in a number of spaces, including in religious spaces.

And so he came in to make the traditional and historical argument, I think kind of playing to some of the comments from the Kennedy opinion that said that history would be some kind of test. And so he was there to give the hearing a little history lesson.

HOLLY: Well, and the idea that the Ten Commandments are historical ‑‑ okay. So great. The Ten Commandments are historical, but I don’t think that that really answers the question about whether they should be in the public schools, whether or not they serve some kind of religious purpose, which they clearly would.

I have heard about David Barton for a long time, and our good friend, former director of BJC Brent Walker had a famous top ten answering the myths of David Barton. But I hadn’t looked at him — I hadn’t seen him in a while, so to see him on the panel and to witness his little odd show was really bothersome.

He brought in a tiny little book that he said was the very first textbook known to be used in America, a 1690 textbook, that had a lot of questions about the Ten Commandments in it, showing that the Ten Commandments had been used in educational settings, I guess, from the beginning of our country. Again, it’s a little bit odd.

He’s basically kind of trying to use history in a way to say that because something existed historically, therefore it is constitutional, which is a big leap from what the Court has said about looking to history and tradition as part of defining the parameters of the Establishment Clause.

AMANDA: Particularly because the 1690 textbook predated public schools, and it predated the U.S. Constitution.

HOLLY: Of course. Yeah.

AMANDA: So this doesn’t seem even a particularly effective use of history to prove a constitutional or No Establishment point.

HOLLY: At the same time, he noted that this is something that he’s obviously cared about for a long time.

In talking about Cecil B. DeMille’s effort to put Ten Commandments monuments everywhere, you know, to promote the old Ten Commandments movie — that, of course, was a big part of people’s story and advocacy back in those 2005 cases about these monuments, because it turns out that a fair number of Ten Commandments monuments across the country were put on different grounds to promote that movie.

So, yes. So David Barton came on strong, saying, This is totally historical; it fits with where the Court’s going. And then the next witness, I believe, was his son, somebody who also represented WallBuilders, the David Barton organization, and Tim Barton made a bold assertion that you needed to put the Ten Commandments in there basically to restore morality to the public schools and to society.

AMANDA: Right. And it’s this tired argument that we’ve heard in other places that tries to make a causal link between the removal of government-sponsored religious exercise in the public schools to ‑‑

HOLLY: Any social problem.

AMANDA: — any social problem we have today. And he repeated that here with some thinly veiled racism about violence and particularly “in inner cities and gang violence.” And then he cherry-picked from the Founders — again a usual strategy for those who are ambassadors of Christian nationalism, cherry-picking from history.

But, again, he said ‑‑ he was kind of answering this implicit question about religious proselytization in the public schools. He said, you know, we’re not compelling people to believe in Jesus; they just need to understand the basis for law and morality.

And so I was left with this question. So do they think the Ten Commandments is a religious document or not? Because in this argument they’re making, they’re even stripping this language of any religious meaning at all and saying it’s only about morality and law.

HOLLY: Well, thank goodness, they only had five minutes to testify, Amanda, because I’m sure he has a long story that he could tell you about what he’s trying to do. But it is hard for us to see that there is any secular purpose for having the Ten Commandments in every classroom.

AMANDA: Well, once the lawyers and the professionals were done, then they had another panel come up. And we won’t go through all of these witnesses, but it was clear that those members of the public who came to testify for the bill were there for a very different reason.

And the first person up was a mother, Tara Beulah, who talked about how the public education system is a disaster, and we need to invite God back into our schools.

MS. BEULAH: (audio clip) How do we fix this? We start by inviting God back into our schools. God is His Word. The Bible says, “My son, attend to my words. Incline thine ear unto my sayings. Let them not depart from thine eyes.” Our kids have to see them in these halls. “Keep them in the midst of thy heart.”

We must allow the Ten Commandments to be posted in every classroom in the state. We also must allow chaplains to come in and aid our student population. We have to get back to the basics. There’s no such thing as separation of church and state in the Constitution. We are a Christian nation, and we should start acting like one.

AMANDA: So the Christian nationalism was on full display in her testimony, and she made no attempt to say that this was anything but a religious reason for her testimony in favor of the bill.

HOLLY: You said it was a very different reason. I think, you know, we could debate that ‑‑ right? ‑‑ how close these reasons are to each other, but ‑‑

AMANDA: Sure.

HOLLY: — certainly that first panel appeared to be just saying that they were taking advantage of this ‑‑ what they would see as a correction in the Establishment Clause jurisprudence. They probably would assume that you could pass this bill and maybe this Court might uphold it, and they would do that in keeping with our religious freedom tradition under the Establishment Clause without coming out so clearly advancing this kind of “Christian nation” agenda that they did in the second panel.

AMANDA: Yeah. No. I totally agree with you, Holly. I think that the first panel was being very careful in their articulation of their reasons. I think that the real reason for these efforts was more obvious and candid by the second panel.

And then on the third panel, we finally had another perspective. We had a pro-religious liberty and Baptist history perspective —

HOLLY: Woo-hoo!

AMANDA: — from ‑‑ yes ‑‑ from a Baptist, John Litzler, who was representing the Christian Life Commission of the Baptist General Convention of Texas, and he was testifying against the bill, raising serious concerns about freedom of conscience and religious liberty. He gave the Senate hearing a short Baptist history lesson about Thomas Helwys, one of the co-founders of the Baptist movement, and his concerns for religious freedom.

HOLLY: Finally. It was good to hear that perspective, a perspective that we, of course, share as Baptists who share the same history. We certainly appreciated that testimony. Mr. Litzler first talked about parental rights, and he did that in relationship to religion.

But I thought that was interesting, because obviously there are a lot of conversations about parental rights these days, and he was very clear in noting that parents — just like Britt Luby noted in that article — should be in the position to teach their children about religion and to do it in ways that are consistent with what they teach at home and in their selected congregations.

And then it was good, of course, to hear that religious reason for keeping the legislature out of this business, and he brought up some of these points about the government picking Scripture and how that takes away from him as a parent the responsibility and right and ability to teach his children what’s most important in the Bible and give it some context to make sure you teach it the way you’re trying to teach your children and nurture them in the faith.

But there were some people on the panel that were not prepared to hear that. As loud as we might sound similarly to Mr. Litzler in saying, keep the government out of promoting religion in the public schools, there was some pushback on the panel, and interestingly, different members made clear that they were Baptist, and of course, displaying that diversity in Baptist life but also, you know, showing that there are a lot of Baptists in Texas, Amanda.

AMANDA: There are quite a few Baptists in Texas. And we talk on Respecting Religion a lot, Holly: No two Baptists agree on everything. That’s just part of being Baptist. And so Senator Donna Campbell is a Baptist, and she was ‑‑ she said she was shocked by Mr. Litzler’s testimony and also irritated by it, and she said, I just don’t understand that. It was clear that she had never heard this Baptist history of religious freedom advocacy before and couldn’t imagine why a Baptist would be concerned about the posting of the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms.

HOLLY: I’m glad that she had a chance to hear the testimony, to at least learn something about Baptist history, maybe for the first time to know that Baptists had defended the rights of conscience from their very beginning.

AMANDA: So I’m glad that made it on the record, but I’m not so sure she got that.

HOLLY: Yeah. In fact, she was so shocked and irritated that she kind of went after the witness and said, you’re a Baptist, and you’re against putting the Ten Commandments in the public schools? Like, Who are you? What kind of Baptist are you? Do you even believe in saying the Pledge of Allegiance? Do you even believe in one nation under God?

AMANDA: As if those are religious beliefs, by the way.

HOLLY: Oh, my goodness. I know.

AMANDA: So that’s the other thing is just this thorough merging of Christianity and patriotism ‑‑

HOLLY: It was remarkable.

AMANDA: — that is Christian nationalism.

HOLLY: Yeah. I felt that the witness did his best to say it’s the responsibility of the church and individual faith groups to educate people about religion. It is not the role of the state. But, I mean, it kind of blew her mind, and that was really disturbing as a pretty clear demonstration that there are many people who have not stopped for a minute to distinguish between their religious identity and their civic identity. And if you have questions, you might want to check out ChristiansAgainstChristianNationalism.org.

AMANDA: We have plenty of resources for Senator Campbell and all other people to access to understand Christian nationalism and how it’s playing out in policies like this one.

Segment 3: Engaging in conversation about the Ten Commandments (starting at 30:01)

AMANDA: So, Holly, this bill is not even a law yet. It has been passed by the Texas Senate. As we record today, it has not yet been taken up by a House committee, although it will be soon, and we don’t know what the House vote will be. So it’s way too early for us to talk about, you know, how this fares on a constitutional level.

But we do want to talk a little bit more about what the religious freedom problems with this bill are. And we can look back to advocacy that BJC has done and that you personally, Holly, have done as general counsel at BJC around cases involving the posting of the Ten Commandments.

HOLLY: I think my prior writings are the kinds of things that I would say if I had a chance to talk directly to Senator Campbell. I’ve written about the Ten Commandments in government displays in the past. Particularly I had to do a good bit of that back in 2004, 2005, when these Ten Commandments cases were making their way through the courts and up to the Supreme Court that ended in decisions, the McCreary County decision out of Kentucky and the Van Orden decision out of Texas, because, of course, BJC was a leader in the conversation, saying that the Ten Commandments are a good idea. The Ten Commandments have religious and historical, theological importance to us, but that doesn’t mean that the government should be posting them on county courthouse walls or even on the capitol grounds. And a lot of the advocacy that we did was really just to get people to think about why that is.

One of the things that I wrote about was how we wanted to have a better conversation, that it wasn’t just a fight between those who want to get rid of any religion in the public square and others who want to force religion by any means possible through the government, but that we wanted people to understand that you could be pro-religion — you could obviously be pro-religious freedom and still think that this was a terrible idea and one that our Constitution should forbid, the government actually selecting particular Scripture and promoting it on government land.

I said that the debate would be much more interesting and productive if supporters of religious freedom would get involved and reframe the issue. Instead, we should use this as an opportunity to talk about how religion is best protected when the government does not try to do the work of the church. And I made some suggestions.

AMANDA: I think that those suggestions are even more important today as we enter these new and yet old waters of posting of the Ten Commandments in public schools. So what are they? What would you have us do, Holly?

HOLLY: Well, you should have conversations where you listen to people and understand their concerns, and then try to get them to see it a different way. First, recognize that, yeah, the Ten Commandments are helpful, helpful teachings. They have broad, popular support. Really the debate is not about the Ten Commandments but about who is responsible for teaching religion.

I noted in my article that just because something offers a benefit does not mean the government can or should promote it, particularly when it comes to religion. I said, I find my Sunday school class extremely helpful, but I would never expect the government to support it. The government can endorse many things, but thanks to the First Amendment, it cannot favor your religion nor denigrate mine.

I think that’s still important today, Amanda, even if the Court no longer follows the endorsement test or the Lemon test. I think that most people would agree that we really don’t want the government choosing whose religion is most important.

AMANDA: And that’s exactly what we have here, a government choosing a particular version of a religious text and promoting it in public schools.

HOLLY: I also always note that there are many societal concerns, many cultural concerns, many parental concerns, things that we might worry about in society, and that religion is not going to gain the center stage and be a productive force by relying on the government go do its work.

Communities of faith, individuals must work hard and demonstrate the appeal of faith, and there’s plenty of things to do. And just slapping the Ten Commandments in a government building or a public school classroom is not going to do the religious work that most religious people think is important and beneficial in their community.

AMANDA: It really cheapens the religious content, to treat it as just a poster to put up alongside any other poster these kids might see in their classroom.

HOLLY: I also would just put aside this argument that somehow the Ten Commandments are the basis of our law. It’s not supported, and while, of course, religion has had a profound influence on the development of our country, particularly on individuals, this argument really promotes a false history, and as you noted, Amanda, a very limited view of Scriptures.

It is incorrect and disrespectful to reduce the Ten Commandments to some secular historical document. They hold a unique place in the history of particular faiths, and that is not something that’s taken into account or seems to be even thought of by these Texas legislators with this plan. So it seems really irresponsible from a historical education perspective as well as a religious perspective.

AMANDA: And I think it’s particularly important that people of faith come forward and voice their concerns about the use of this religious text in public school classrooms. Holly, as you wrote and then Britt Luby quoted you in her more recent piece, “Those who share the BJC perspective on religious liberty will continue to promote the Ten Commandments and other scriptural mandates in a way that the Bible encourages, by writing them on our hearts, as the prophet Jeremiah instructed.”

So we are going to post a link to that piece in show notes as well as some other resources we have at BJConline.org, because unfortunately, this is a live issue again and in ways that I had thought had long been settled, but we need to have a strong response when these bills are raised, and if this bill is ultimately passed by the Texas legislature, it could be coming to another state legislature near you very soon.

HOLLY: Before we close today, we want to say thank you for listening. Just last week, we were honored with new awards from the Religion Communicators Council. We won best in category for our podcast episode that I mentioned earlier, the one wrapping up the Kennedy v. Bremerton decision last year. It was an episode we did in front of a live audience, and if you want to go back and listen to it, it’s episode 21 of season 3.

We also got an award of merit for our current season, season 4. We have a small staff, but this is a labor of love for us, and we’re so glad you’re joining us for all these conversations.

AMANDA: Also, we’ve had a lot of new listeners in the past few weeks, most of you coming over from the Strict Scrutiny podcast. Welcome. We’re glad that you’re here, and if you’re new and enjoying the show, we ask that you give us a five-star rating or review. That helps others find the show.

We want this to be a place people can come for honest conversations about religion and the law, and we thank everyone for joining us. We always love hearing from you, and you can email both Holly and me at [email protected].

HOLLY: That brings us to the close of this episode of Respecting Religion. Thanks for joining us for today’s conversation. For more details on the articles and resources we mentioned, visit our show notes.

AMANDA: If you enjoyed today’s show, share this program with others on social media and tag us. We’re on Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube @BJContheHill, and you can follow me on Twitter at AmandaTylerBJC.

HOLLY: Thank you for supporting this program. You can visit our show notes for a link to donate to support this podcast.

AMANDA: And for more episodes, you can see a full list of shows, including transcripts, by visiting RespectingReligion.org.

HOLLY: We encourage you to take a moment to find out more about BJC and how we’ve been working for faith freedom for all since 1936. Visit our website at BJConline.org for a look at what we do and some of our latest projects.

AMANDA: Join us on Thursdays for new conversations Respecting Religion.