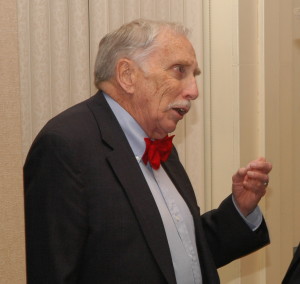

Dunn discusses historic right to religious liberty

2007 Shurden Lectures held

By J. Mark Brown, Carson-Newman News & Publications, with BJC Staff Reports

Carson-Newman College hosted the second annual Walter B. and Kay W. Shurden Lectures on Religious Liberty and Separation of Church and State February 26-27. The Shurdens, former Jefferson City residents when Walter served on C-N’s religion faculty three decades ago, were joined by a host of family and friends for the two-day event sponsored by the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty.

The three-lecture series was delivered by James Dunn, professor of Christianity and Public Policy at Wake Forest

Divinity School and president of the Baptist Joint Committee Endowment. His remarks considered the history of church and state separation, explored the traditional Baptist confession of faith, and defined, in a student chapel, what separation is and is not.

In his opening address, titled “Challenging Religion: Ours is … We are … ,” Dunn cited four Americans without whom religious liberty would not exist. “Chopping the continuum of contributions by Roger Williams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and John Leland into arbitrary divisions is but one design for getting back to the Bill of Rights’ beginning,” he said.

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion,” he quoted. Then he recalled being part of a group that made a 1964 visit to the chambers of Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black. “No law, what does that mean?” Dunn said, recalling a question a fellow visitor asked of Justice Black.

“Well, it means two things,” Dunn reported Black as saying. “First, it means NO, and second it means LAW! No law, favorable or unfavorable.”

That Americans are blessed to have a constitutionally guaranteed freedom to worship, or not to worship, said Dunn, can be attributed to the passion and diligence of the four men.

Of Williams, Dunn said, “Roger Williams fathered philosophically the American experiment in freedom of religion … He shaped his colony of Rhode Island into the home of the otherwise-minded.”

Although his principles and contrarian ideals cost him both societal and creature comforts, Dunn championed Williams’ willingness to pay the toll of contending that freedom is more important than toleration.

“He despised toleration as the measure of the majority religion’s relationship with dissenters,” said Dunn. “Toleration is a human concession. Liberty is a gift of God.” By refusing to concede the government’s claim to a standardized religion, including taxation to support ministers, Williams was the incarnation of, “the freedom of religion guaranteed in the First Amendment.”

“Williams,” claimed Dunn, “is disproportionately important because he first challenged the old world patterns of toleration, theocracy, church-states and state-churches. He was banished, ostracized, ridiculed and thought to have windmills in his head. He died poor and rejected, with not much to show for his labors … except the experiment of religious liberty and the most vital churches in the world.”

While Williams lit the candle of religious liberty in the fledgling nation, Dunn credits Thomas Jefferson with using the flame to build a fire. In keeping with his stated wishes, Jefferson’s tombstone notes only three things: his composition of the Declaration of Independence, his establishment of the University of Virginia, and his responsibility for Virginia’s Statute of Religious Freedom. Although there is not a word about his inventions, his service abroad or even his presidency, he made sure that he is remembered for helping to keep religion and government from intermingling, said Dunn.

Calling James Madison the single most significant figure in the establishment of the First Amendment, and therefore separation, Dunn said, “For all of Roger Williams’ philosophical and practical precedents, and all of Thomas Jefferson’s brilliant accomplishments, it was little Mr. Madison who institutionalized religious liberty.”

“Many people today fail to appreciate Madison’s role as author of the Bill of Rights,” he said, noting that history has neglected him because he was reluctant to the idea. Once he saw that states might not ratify the Constitution without guaranteed freedoms, he put aside his objections and wrote the document.

After crediting Williams, Jefferson and Madison for their efforts Dunn said all of their work would have been for naught save John Leland. “No one more than Leland captures the color and people power of those who demanded guarantees for religious liberty and civil rights,” praised the Wake Forest Divinity professor. “It was Leland and hundreds like him who turned the tide for religious freedom and even for the adoption of the Bill of Rights.”

In his second lecture, titled: “Response Able and Free,” Dunn outlined the difference between a creed and a confession. He argued that Baptists historically have not had theological, ethical or political creeds, but they have had an ecumenical and biblical confession of faith, “Jesus Christ is Lord.” This “vital and lively” confessional, according to Dunn, issues in a coherent set of beliefs that have as “a common core, the freedom of conscience.”

Dunn told C-N’s Tuesday morning chapel audience, “If we know anything at all of history, law, scripture, human nature, and the spirit of Jesus, then we must get off our apathies and speak up for freedom of conscience. When anyone’s religious freedom is denied, everyone’s religious freedom is endangered. When government requires religion, it makes a monster of it. When government meddles in faith, it always leaves a touch of mud. If religion is not voluntary, it cannot be vital.”