By Cherilyn Crowe

“Religious freedom – like all other freedoms – has always been, for African-Americans, complicated at best,” said the Rev. Dr. Raphael G. Warnock during a day-long exploration of the relationship between religious liberty and the black church.

On Nov. 10, the Baptist Joint Committee sponsored a symposium focusing on that complex intersection along with the Howard University School of Divinity. Held at the Howard University School of Law in Washington, D.C., the symposium featured a variety of voices. Warnock, pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, delivered a lecture and participated in a panel discussion.

“Religious liberty is one of the hallmarks – and part of the bedrock – of American democracy,” Warnock said as he reviewed the ways in which the First Amendment provides freedom of – and freedom from – religion. But, he noted the convoluted relationship for African-Americans.

“The freedom provided by the separation of church and state has been of limited good for those who have known the violent encroachment of each upon their liberty, separately and in tandem,” he said.

Warnock reviewed history that continues to shape America today, noting that slaveholders had concerns that religious freedom for slaves might lead to political freedom. He also pointed out the glaring hypocrisy of colonists fighting the British for freedom from tyranny while keeping people as slaves.

“It is against the oxymoronic backdrop of the legacy of a Christian slaveocracy that black people have had to fight for their liberty and their religious liberty, and have leveraged each in the pursuit and maintenance of the other,” he said.

Speaking only two days after the election of Donald Trump as the next president of the United States, Warnock reviewed some of the policies proposed on the campaign trail, such as religious tests in immigration policy, that caused him concern and are now serving as a call to stand up for others who are marginalized.

He invoked the words of Martin Niemöller, the protestant pastor who was a critic of the Nazi regime in Germany. Warnock gave his version of Niemöller’s famous words, making one key adjustment: “[W]hen they came for the socialists I did not speak up, because I was not a socialist. When they came for the trade unionists, I did not speak up because I was not a trade unionist. When they came for the Jews – in our context, the Muslims – I did not speak up, because I am not a Muslim. And then they came for me, and there was no one left to speak.”

Warnock told the crowd that liberty – and religious liberty – are in peril. “Could it be that America’s anti-slavery church – the black church born fighting for freedom, religious freedom and political freedom – is uniquely shaped and situated both to perceive the threat and to lead in the important work of this manner?”

Warnock ended his lecture with a reflection on the words of Martin Luther King Jr., who said the ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands at times of comfort and convenience. Warnock extended that to the measure of an institution. “In the quest for freedom and justice, and at a time when many would confuse God and government, Dr. King said that a time comes when silence is betrayal. I submit that, for the black church – a church born fighting for liberty and religious liberty – indeed for all of us, regardless of race or religion, that time is now.”

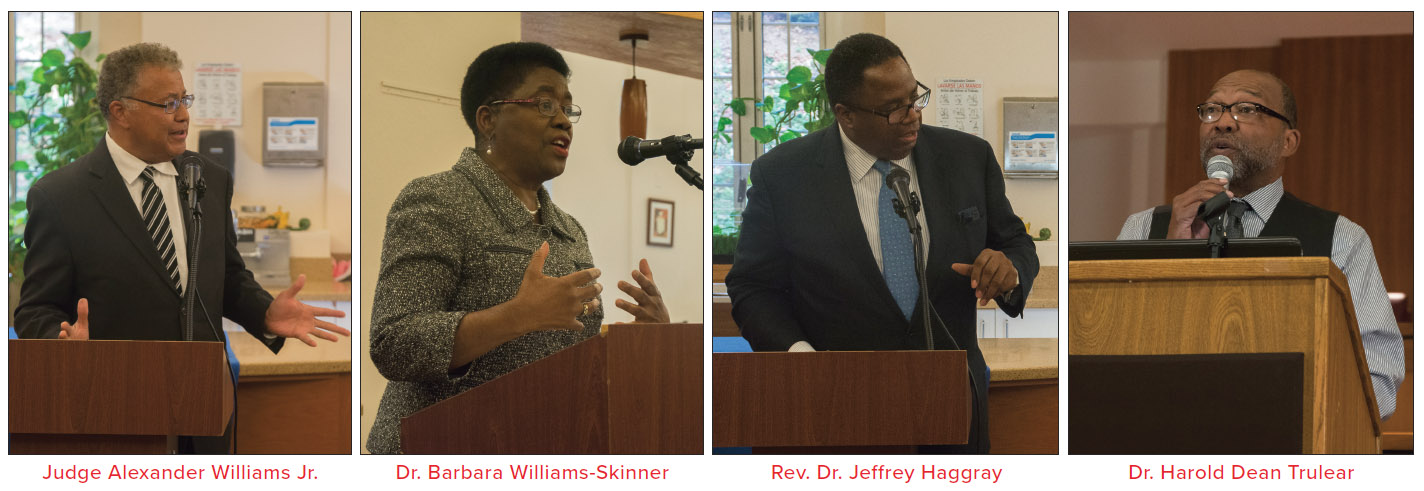

Dr. Harold Dean Trulear offered a faculty response following the lecture. An associate professor of applied theology at the Howard University School of Divinity, Trulear applauded Warnock’s words and discussed how black churches have a pragmatic approach to political engagement.

Trulear challenged the audience to be aware of issues that arise when there is a divide between social responsibility and personal holiness, and he pointed out the need for prison ministry to shift from outreach to reclamation. “The black church cannot afford to hug the illusion of freedom in an age of mass incarceration,” Trulear said, who also serves as the director of the Healing Communities Prison Ministry and Prisoner Reentry Project of the Philadelphia Leadership Foundation.

For the panel discussion, the crowd packed into the dining hall for further exploration of the topic. Moderated by the Rev. Dr. Jeffrey Haggray, executive director of American Baptist Home Mission Societies, the panel featured Warnock alongside Judge Alexander Williams Jr., a former federal judge who teaches at the Howard University School of Law and School of Divinity, and Dr. Barbara Williams-Skinner, who heads the Skinner Leadership Institute and is a former executive director of the Congressional Black Caucus.

In a wide-ranging discussion, Haggray led the panelists to explore ways the black church has benefited from religious liberty and the challenges it faces.

Williams noted that the black church historically has been the only institution addressing the social, economic and political problems and degradation facing African-Americans and other minorities, and black churches were the foundations from which civil rights leaders emerged.

“But for the black church and all that they stood for across the years, I don’t know where we would have been,” Williams said, pointing out how integral the institution was in supporting the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act. He said he had concerns about how little churches are involved in movements today, and they are having problems resolving and interpreting the great moral issues of our time, such as same-sex marriage and abortion.

In her opening remarks, Williams-Skinner continued that line of discussion, pronouncing that a church founded in freedom and resistance to systemic racism is of no use to black people if it does not continue that resistance. After discussing the aging black church’s disconnect from millennials, she said there is a divide between how we see advancement of the black cause. “The Black Lives Matter movement is the only movement connected to black people not born in the black church,” she said, providing evidence of a societal shift.

Warnock expressed his concerns about the divide between the pastors of the black church and the scholars of the black church, referring to the disconnect as being between “Jerusalem and Athens” or “ivory towers and ebony trenches.” He advocated for more dialogue between the two in order for the academic conversation to connect with the energy of the church and its unique gifts and insights to the relationship between religious liberty and liberty.

Haggray pointed out that, contrary to popular sentiment, the separation of church and state does not keep religious voices from influencing the government. Warnock gave examples of ways the church can work with the government, but he said it is crucial for the black church to maintain its freedom, autonomy and independent voice. And, when working with the government, he said, “Just make sure your nonprofit doesn’t turn you into a non-prophet.”

The BJC’s Symposium on Religious Liberty and the Black Church was held in conjunction with the Howard University School of Divinity Centennial Alumni Convocation. It is the second in a series of lectures sponsored by the Baptist Joint Committee to increase its demographic reach, following last year’s Lectures on Social Justice and Religious Liberty at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California. Future lecture series will take place on different campuses, with the goal of bringing religious liberty discussions and the BJC to diverse communities.

You can watch an archived video of the entire lecture at this link.

From the November/December 2016 edition of Report from the Capital. You can also read the digital version of the magazine or view it as a PDF.