Supreme Court’s COVID rulings raise questions about wider religious liberty impact, emergency procedures

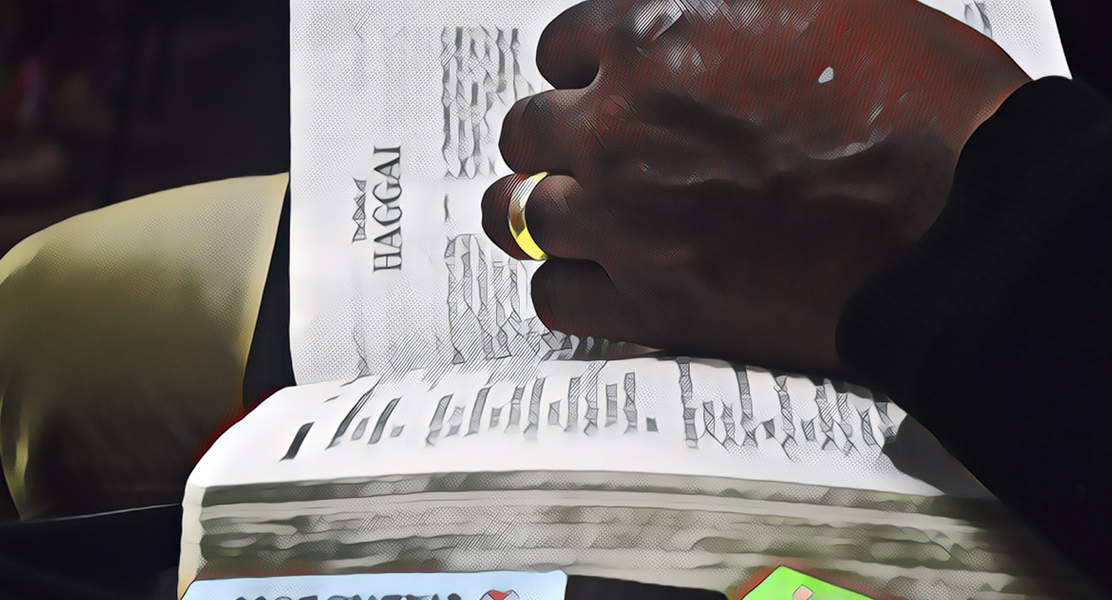

Earlier this month, the U.S. Supreme Court again issued an emergency ruling barring the state of California from enforcing a public gathering restriction – one designed to limit the spread of the coronavirus – against a church. In Tandon v. Newsom, the court ruled that home Bible studies are exempt from the state’s regulations limiting gatherings in homes to three households.

The 5-4 decision marked the fifth time since the addition of Justice Amy Coney Barrett to the bench that the Court has overturned the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and issued an injunction against a COVID-related public health order from California and in favor of a house of worship’s religious liberty claim. The unsigned (“per curiam”) majority opinion reasons that if the state allows hair salons, retail stores and restaurants to allow more than three households, that it must also allow home Bible studies to do the same under the First Amendment.

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Elena Kagan says that’s treating “apples and watermelons” as the same:

California limits religious gatherings in homes to three households. If the State also limits all secular gatherings in homes to three households, it has complied with the First Amendment. And the State does exactly that…

Over the last several days, many legal scholars and commentators have weighed in on this ruling. Based on interviews for Slate with professor Steve Vladeck of the University of Texas School of Law and professor Jim Oleske from the Lewis and Clark Law School, Mark Joseph Stern argues that the Tandon ruling “radically altered the law of religious liberty.”

Under this doctrine, any secular exemption to a law automatically creates a claim for a religious exemption, vastly expanding the government’s obligation to provide religious accommodations to countless regulations. In Tandon, for instance, the Supreme Court held that California had to let people gather indoors for Bible study because it allowed them to gather indoors to get a haircut, eat, or take a bus;

Also concerning to many is the manner in which the Court made these COVID-related decisions: as an emergency injunction with no normal briefing, no oral argument and no substantial opinion explaining its ruling. Vladeck explains:

[Tandon] was the seventh time this term that the Supreme Court has issued an emergency injunction pending appeal. All seven were in COVID free-exercise cases. The first was in November… Before November, it had been five years since the court had issued an emergency injunction. Those who like these decisions are getting increasingly comfortable with the court flouting and defying its own internal standards and rules for this kind of relief simply because they like the result. In the process, they attack critics for being insufficiently sensitive to religious liberty. And that’s a preposterous claim. These rules exist for a reason.

Regardless of whether First Amendment law writ large has been radically altered as some experts suggest, the balance of interests between religious liberty on the one hand and the state’s need to protect public health and safety during a pandemic emergency on the other has undeniably shifted since Justice Barrett replaced the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.