THE BJC FELLOWS

2024 BJC Fellows

What does it mean to recognize and protect faith freedom for all? Which stories have been ignored or overlooked by the common historical narratives? How do we create a brighter future that recognizes everyone’s humanity?

Our 2024 class of BJC Fellows explored these questions and more during their seminar in Colonial Williamsburg, where they engaged in experiences that provided a theological, historical and legal look at religious freedom.

The BJC Fellows come from diverse theological, educational and geographic backgrounds, all united in their call to defend faith freedom for all. This year’s class explored the importance of listening to all narratives; in addition to the stories on the grounds of Colonial Williamsburg, the class heard from an archaeologist who explained how building structures were previously prioritized in archaeology instead of the stories of the people who lived and were buried there.

Scroll down to read reflections from the 2024 class, and keep scrolling to read more from Dr. Corey D.B. Walker about the new stories we can learn from the grounds of Colonial Williamsburg.

For more on the BJC Fellows program, visit BJConline.org/Fellows.

I came to the BJC Fellows Program passionate about the history of religious freedom and eager to become a better advocate for its present and future. As a Ph.D. student in American religious history, much of my knowledge about religious liberty comes from the classroom. However, I’ve long admired the work that BJC does to promote faith freedom for all, and I was excited for the opportunity to add some skills to my religious liberty toolkit. Through my experience as a BJC Fellow, I’ve gained a renewed appreciation for the historical roots of religious freedom in America and a newfound confidence in my role as a voice for religious freedom, both inside and outside of the classroom. …

Margaret Hamm / Somerville, Mass.

On our very first day in Williamsburg, the Rev. Dr. Corey D. B. Walker posed two questions to us that stuck with me in a meaningful way: “Why are we writing the stories we write? For whom?” These questions centered my time in Williamsburg and will continue to animate my work going forward. While they’re certainly important questions to ask for purely academic work, I find them even more crucial to consider as a budding scholar-advocate. Effective advocacy is all about storytelling, and the story of religious freedom in America should include people of all religious traditions and none, people of all races and ethnicities, and people of all gender identities and sexualities. For me, it’s imperative to acknowledge how systems of white supremacy, patriarchy, homophobia and xenophobia have historically kept many out of the narrative of religious freedom and to correct those injustices going forward.

One of the most impactful moments for me during our time in Colonial Williamsburg was getting out of the classroom and taking a walking tour of some of the historical sites in the area. Whether walking through the rooms in George Wythe’s house or standing in front of the archaeological site of the First Baptist Church of Williamsburg, the Rev. Dr. Walker’s questions were made real right in front of me. I tend to think of religious freedom as something that’s found in law school textbooks or Supreme Court decisions, but the walking tour reminded me that religious freedom is a theological, political and cultural ideal that exists vibrantly within our places of worship, our schools and our homes. Ultimately, this experience affirmed to me that the history of religious freedom in America is deeply contested, and it’s up to us not only to reclaim this narrative but to create a new history for future generations.

The greatest gift of my time in Colonial Williamsburg, though, was the deep, long-lasting connections I made with my fellow cohort members and with members of the BJC staff. It was invigorating to meet such kind, thoughtful, and driven people who were all committed to the pursuit of religious liberty. The fact that each of us brought vastly different questions, identities, and motivations to the experience only made our relationships stronger, and I had uniquely meaningful conversations with other members of my BJC Fellows cohort. Post-Williamsburg, one of the other BJC Fellows and I started our own writing group to continue to think collaboratively about the uncovered histories and future possibilities of religious freedom in America. From this time spent in community, I feel confident that I not only have the tools to succeed in my own personal journey of religious freedom advocacy but that I’m also well-equipped to help others in our collective fight for faith freedom for all.

As a whole, this experience has energized me to take what I’ve learned back home to the communities I care about. While I’m lucky to live in an area of the United States where the threat of Christian nationalism isn’t experienced quite as directly, I believe that it’s incredibly important for all Americans to learn about the dangers of Christian nationalism and to advocate for religious freedom, regardless of where they live. Religious freedom is a crucial part of all the issues that I care about — from reproductive freedom to LGTBQ rights to racial justice — but this truth isn’t clear if how we talk about religious freedom excludes the very people it impacts the most.

To my surprise, I woke to a lament when I returned home from the BJC Fellows Seminar. Tears filled my eyes as I reflected on the historical underpinnings of religious liberty in America. We read Endowed by our Creator by Dr. Michael Meyerson, and within the pages, he unveiled the framing of the Constitution and the formation of the First Amendment. I came to this experience with some knowledge of the mistreatment inflicted upon others in the name of religion. However, I was shocked to learn the extent of the power struggles between church and state as well as the violence that occurred during the framing of this country. So many lives were lost and degraded, and voices were silenced because of ill-informed theology about God, freedom and religion. …

Lakia Marion / Knoxville, Tenn.

Although the Constitution’s language speaks of a diverse and free nation, I discovered through our readings and open discussion that the plight of those on the margins remained limited. For example, enslaved peoples and other ethnic groups were not seen as human or worthy of freedom—racial or religious freedom. Simply put, their human rights were not considered. They were invisible and treated as spiritual and economic commodities. The experience of walking the grounds at Colonial Williamsburg and learning the history of my ancestors’ plight is one of the reasons I woke up to a lament. Still, most importantly, tears filled my eyes because America’s history demonstrates that our inability to embrace “otherness and difference” originated during colonization.

History informs us that the language of Christianity here in America was shaped by those who had the most power – white males. Their proximity to law, government, and religion granted them the power to implement policies shaping every aspect of our social institutions. These policies were not formed to include all members of society, thus leading to the injustices and inequalities we see today. Additionally, I believe the fact that all members were not included in the framing of this country has contributed to our inability to see that we share a common humanity.

Dr. Sabrina Dent asked, “Who has the right to be human?”

I instinctively answered “everyone” in my heart.

The answer to this question is obvious, right?

We all have the right to be human. Yet, in our world, we are quick to label, categorize and make snap judgments about each other before learning the essence of our neighbor. After my 2024 BJC Fellows Seminar experience, this question echoes in my heart and mind: “Who has the right to be human?” This question has broadened my view of God and who I am to be in relation to others. My faith in God and my commitment to follow Jesus convicts me to love my neighbor as myself. My neighbor is whoever I encounter, and I am to love them regardless of race, class, gender or religious belief. I walk away from this experience with a more pronounced understanding that we share a common humanity.

To this end, this is my call to action: to be an agent of healing on the earth. I will do this by creating healing spaces in my community for ALL people to share their stories and experiences in a safe environment without judgment. I firmly believe that the healing of nations is possible. I shall endeavor to use the insights from this experience to engage in courageous conversations that challenge injustice and inequalities so that reconciliation may abound in families, communities and nations.

I came to Colonial Williamsburg feeling settled in my understanding of religious liberty. My experiences instilled a passion for the freedom of religion, alongside other civil liberties, and linked the value of that freedom with its place in the Constitution. I saw the liberty to decide our deepest convictions and act accordingly as preeminent for its association with the highest law in the land. Enshrined in our nation’s most supreme legal text, religious freedom had no better bedrock.

What I read and heard as a participant in the 2024 BJC Fellows Seminar reframed my understanding of religious liberty, powerfully shifting its focus from a legal to human constitution. …

Jamil Grimes / Nashville, Tenn.

During the seminar’s reading and discussion of Dr. Michael Meyerson’s Endowed by Our Creator: The Birth of Religious Freedom in America, I recalled the author’s description of John Leland, a Baptist leader who pushed for religious freedom. “Fundamental to his philosophy was the belief that the ‘rights of conscience and private judgment’ were inalienable rights,” wrote Meyerson, echoing some of Leland’s words, “that no government could acquire and no individual could surrender: ‘Like sight, hearing, thinking and breathing, they are always attached to individuals’” (. To be sure, the legal underpinning of religious liberty remains deeply important. Dr. Meyerson opened a window into the strenuous efforts to craft a sufficient legal articulation of religious liberty, efforts complicated by both the diversity of beliefs in early America and the beliefs of the Framers themselves. There is truly much at stake in this hard-fought expression of religious freedom. This includes both a staunch defense of the No-Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause. And yes, we will arbitrate many disagreements over religious liberty in courts of law, where such matters are litigated by attorneys and ruled upon by judges. But the more I engaged with the early history of religious freedom, the more I realized that there is a higher plane in the fight for freedom of religion. That higher plane is nothing less than an understanding of what makes us human and who we include in that “human.” Religious freedom is not just about our legal reasoning. It is about our moral imagination.

If our time with Dr. Meyerson made clear that early voices of religious freedom prioritized its status as a natural right, an entitlement recognized by law but not given by it, [O]ur session with Dr. Sabrina Dent concretized religious freedom as a human right and a matter of human dignity, universal in aspiration but limited in application. This moment offered a sober reminder that not all people have been recognized as being fully human, that the same Enlightenment thinkers responsible for liberal ideas like religious tolerance also perpetuated racist hierarchies in which distance from whiteness meant an absence of cherished human virtues, such as rationality. And as someone of African descent, I think especially of Black people, long valued for their bodies but not for their minds. Dr. Dent encouraged me to see that thinking and writing more expansively about religious liberty requires that we expand our scope to take in far more than those figures frequently cast as religious dissenters. The work of religious freedom advocacy depends on our ability to recognize the limits of religious liberty at the margins, among underrepresented and vulnerable communities. Religious liberty proponents must reckon with the history and ongoing denial of religious liberty that proceeds less from a perception of religious difference than one of human difference.

In some cases, as Jennifer Hawks’ and Amanda Tyler’s presentations made clear, political difference becomes to point of exclusion. But religious liberty must extend to everyone, if its promise as a universal right is to be taken seriously. Religious freedom, like any right guaranteed or affirmed by the Constitution, does not belong by one side of the political spectrum or a single constituency. Notwithstanding some associations of religious liberty claims with misplaced efforts to restore America’s status as a “Christian nation,” freedom of religion is not the preserve of right-wing of dogwhistlers, those wishing to signal a “return” of God to schools and halls of power. At its best, religious freedom is non-partisan. And defending religious liberty involves nothing less than a willingness to defend the rights of those who religious beliefs prescribe values opposed to our own. Ardent Christians, whether conservative or progressive, and those of no faith at all, must be careful not to project their beliefs onto the past as a way to exclude those they disagree with in the present.

Long before arriving, I had witnessed my mother’s passage through law school. Surrounded by weighty books and walls plastered with notes, she would translate legal jargon into language her young child could latch onto: “We have rights, and those rights are in the Constitution.” I later worked for over six years in municipal law enforcement, a career inaugurated by an oath to support the U.S. Constitution. Having so sworn, I worked to become a knowledgeable interpreter of the Bill of Rights and the limits it imposed on the government. I did not expect my time at the 2024 BJC Fellows Seminar to reconnect my passion for religious freedom to my deepest held liberal beliefs, but that is precisely what the experience did. I came away as someone even more confident in liberty of conscience and certain in the conviction that to be human is to have an inherent capacity for deliberation and judgment. Religious freedom isn’t just some abstract idea articulated on dusty parchment. It is a recognition of who we are as human beings: thinking creatures, wonderfully made. Respecting the right of religious freedom isn’t just about respecting the law. It’s about respecting humanity, and the dignity demanded by human being.

Words create the world we live in. Words are powerful and have the ability to heal or harm, to build up or tear down, to take your breath away or to help you breathe deeply. Words have lasting effects. As a pastor, I spend a good deal of time thinking about the words I use and paying attention to the words I hear all around me. It seems more and more that I hear words of hate and harm coupled with the words of my Christian faith. I hear Bible verses used as reasoning to deny reproductive and gender-affirming health care. I hear rhetoric around God’s “chosen” presidential candidate. I see lawmakers in other states trying to mandate teaching the Bible or posting the Ten Commandments in public schools. Christian nationalism is nothing new, but it is a consistent and ever-growing danger. …

Rev. Leigh Curl-Dove / Seattle, Wash.

My time at the BJC Fellows Seminar deepened my appreciation for BJC’s work and further cemented my commitment to the intersectional work of faith freedom for all. During our time in Colonial Williamsburg, the speakers continually reminded us of how intersectional religious freedom is. We cannot talk about religious freedom for all people unless we look at the full history and see who is missing from the narrative.

The reality is that the United States was founded by white, land-owning men. The Founders wrote the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution with people who looked like them in mind. When they wrote, “all men are created equal,” did they really mean all men or just white, land-owning men? If all “men” are created equal, what about women? When they said, “We the People,” did they mean all people or just the people they considered to be people—to be human? These words that most Americans know, words American children have grown up memorizing in school, have shaped our world and our mindset. Apart from the full story, these words have created a harmful narrative of idealism and exceptionalism erasing those the Founders did not consider “people” from the story.

My time in Colonial Williamsburg further showed me just how crucial it is to tell the whole story, to resist the urge to sanitize or idealize. We can create a better world where all people truly are people, but not until we pay attention to the full history—not until we pay attention to and listen for the stories of the people who were not given seats at the table, who were not given a voice.

In one of my favorite sessions led by Dr. Sabrina Dent, Director for the BJC Center for Faith, Justice and Reconciliation, she gave us her definition of religious freedom—religious freedom is the freedom to be fully human. Her words were an “aha” moment for me. Her words were a charge to go out and work for a world where all have the freedom to be fully human. To do that, we have to expand the table. We have to make space and place for all people, especially the most marginalized among us. We can craft new words and a world where there truly is faith freedom for all.

The unmitigated gall of this nation’s Framers in creating documents that spelled out freedom and humanity has led us to believe these documents, such as the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution, are infallible and inerrant, which completely disturbs my very being. What I think is missing from the narrative of the conversation around the creation of the country and the work of religious freedom is the psychological framework of the Framers.

I make this statement because, as a black embodied, queer female, I am aware that I was never a part of the Framers’ thoughts when they created the documents that framed and shaped what we now know as the United States of America. During one classroom conversation, I felt as if I had made a quantum leap into the space of my transhumanist thought of weaponizing my own body as a technology for use when we discussed that “‘We the People’ is still expanding.” …

Rev. Margaret Conley / Cartersville, Ga.

The shock of those words hit me at my core because clearly, at one point, someone was not included in this opening phrase of a document that created this “land of the free… .”

My experience during the week was stuck with the statement that “‘We the People’ is still expanding.” What does that mean, that “We the People, are still growing?” Are “people” still being defined by the standards of white men who could not even define themselves? Are people still being defined as less than human and given a fraction of humanity to meet the need for economic acquisition?

The Framers had an opportunity; they took it upon themselves to define what humanity is, and thus, this brings me to my thoughts about how “We the People” are still being defined. What I did gather from this week, being stuck in the era of the freshness of “We, the People,” is that America was built on its own trauma response to the Framers of this nation. And those who came — those who in some other place and time, appeared to have lost some level of dignity and personhood — attempted to gain their understanding of humanity again by saying they discovered something that was already inhabited. The Framers were trying to make right for themselves with no focused thought on how they were bringing pain, harm, and death to others.

From a bioethical standpoint, with theology leading out in the understanding, we see from a theological standpoint that these individuals were taking upon themselves this space to determine what God had already determined to be. Well, they decided that they would define who and what could be human and animal. From a psychological standpoint, the Framers used what was mentally available because physical freedom was obtained without freedom of mind being made well. It makes me ask, “What was the capacity of the Framers in their minds that they thought was right to define humanity so that we could have the notion of thinking that ‘We the People’ could be an expanding thought? From a sociological standpoint, was it in the Framers’ minds that they could own bodies?” They could steal land from others and then claim it as their own, reproduce it, resettle it and then give rules to that land as if it were God’s gift. And in my thinking, I can only assume they thought this to be right based on the biblical notions of being “chosen people.” Moving from captivity to being promised a land that flowed with milk and honey, which was already inhabited and tended to by others. And then, from an anthropological standpoint, what does it look like historically that we are still in a space where we are defining humans and people? What does it look like that we sit in spaces where, in 2024, we are defining what humanity is, who can be, and what is fully human? We decide who needs to be caged, what types of racially aligned jobs are being offered, or who needs to be killed for the sake of liberation because they are not our types of “We the People”?

It is sad that the Framers thought and dismissed the value of writing down instructions to revisit this country’s ‘sacred’ documents. Though we seem to think it radical the offer of religious freedom in the work that framed this country, we also like to dismiss what that term really meant and even how segregation in the settlements of this nation started with their wounds from the lack thereof. I am saddened, yet I embrace levels of hope that, one day, we will move away from the ever-expanding thoughts of defining bodies and humanness. We will move into allowing people to genuinely experience religious freedom from the context of their humanity because “We are the People,” and that is something that does not need to be defined.

Growing up in the church, I saw how religion could uplift people and provide a sense of community, but I also saw how it could cause significant harm — primarily through sexism, classism, ageism, ableism, racism and favoritism. Watching beloved LGBTQIA+ members leave the church because of how they were treated — and seeing how that shattered their sense of worth, identity and belonging — fundamentally changed how I viewed the church I thought I knew. This, coupled with broader research into religious abuse and its devastating impact on individuals, families and communities, fueled my commitment to creating ministries that are truly diverse, equitable, inclusive, justice-oriented and trauma-informed. …

Brittany Washington / Fort Worth, Texas

Participating in the BJC Fellows Program further opened my eyes to the broader ways religious abuse can manifest, especially through racial discrimination and oppression. The 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, which took the lives of four young Black girls, is a heartbreaking example. This church was more than a place of worship; it was a critical hub for civil rights activism. The bombing was a deliberate act of terrorism by white supremacists designed to intimidate and perpetuate racial segregation. These attackers believed they were upholding a divinely sanctioned social order driven by racial hatred and a twisted version of Christianity aligned with white supremacist ideologies. This devastating event shows how religion has been misused to justify violence against marginalized communities.

Reflecting on the legacy of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who led faith communities in matters of justice, demonstrated how faith aligned with justice can be a force for good. I especially appreciate his direct call to action to the church, stating, “It must be the guide and the critic of the state and never its tool… [Furthermore] If the church does not recapture its prophetic zeal … it will become an irrelevant social club with no moral or spiritual authority.” His words energize the church to demonstrate ethical practice that does not impede the separation of church and state, it calls out systems and practices that inflict harm on the community, and advocates for the humanity, safety and freedom of all people.

The path forward in the religious landscape and the public square requires a strong commitment to healing justice, a movement that heals the deep wounds of the past, while addressing disproportionality and injustice amongst minority and marginalized communities. My experiences at the BJC Fellows Seminar and upbringing in the church deepened, clarified and revived my vision for and call to the work of religious justice. I am committed to the principles of love, compassion and respect, which ensure that all people — especially those who have been marginalized and minoritized — find a place where their humanity is honored and their voices are heard.

Since returning from the BJC Fellows Seminar, I have been energized to get to work. I often see threats to religious liberty in my own context, and it feels overwhelming with how blatantly Christian nationalism is intertwined into our state politics in Tennessee. However, one of the most helpful things that BJC Executive Director Amanda Tyler pointed out was that these issues exist on a spectrum. Not every example of Christian nationalism or every threat to religious liberty is as blatant and overt as the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. This framing helped me re-examine the instances in my own context in which Christian nationalism or Christian supremacy might exist. …

Rev. Wesley King / Nashville, Tenn.

In Tennessee, we have a legislature in which all claim Christianity as their faith tradition, not matter their party affiliation. In Tennessee, it is hard to get elected if you don’t claim the Christian faith. Thus, as you might imagine, it is often Christian chaplains, ministers and pastors who pray the invocation before legislative sessions. And while the fact that they are all Christian isn’t an issue, the legislation that is put forth often has a largely Christian hue to it As a Christian pastor in the Disciples of Christ tradition, I am called to ask, “What voices aren’t being heard? Which voices are not at the table?” Thus, I must fight against Christian supremacy to ensure that all of my neighbors’ voices are being heard.

There are certainly examples of blatant Christian nationalism in Tennessee. For example, people in Rutherford County protested and attempted to block the building of a mosque, which finally did open in 2012. Some citizens didn’t consider Islam a religion, therefore they didn’t feel they were infringing on their neighbors’ right to the free exercise of religion. There are also many less overt examples. Earlier this year, the Tennessee General Assembly passed HB 2125, which names the month of November as “Christian Heritage Month.” This bill doesn’t mandate the teaching of Christian heritage in public schools or mandate observation by state employees, but I would argue that it is still Christian nationalism because it seems to elevate one faith over the others. There was no bill to specify a Muslim Heritage month, or a Pagan Heritage month. Because of this, one could argue that the state is indirectly establishing a religion by privileging one faith over all others. Framing Christian nationalism as a spectrum ensures that my colleagues and I aren’t just waiting for the more blatant and dangerous examples before we act.

I am so grateful to have had this experience and cannot overstate how formative it has been for me. I believe that this experience has not only prepared me for a Ph.D. program, but I believe it has better prepared me for my ministry.

It’s important to raise awareness about our history and its effects on people with various perspectives and narratives, and two specific events on the day I left the 2024 BJC Fellows Seminar made it personal for me. I recognized that I am already practicing several types of advocacy in my interactions.

I believe that anyone can listen to a different viewpoint, even when it challenges us. It’s those very conversations with people different than us that help us all to develop and grow. …

Sejana Yoo / Temple, Texas

Early on our final morning of the BJC Fellows Seminar, I chose to interact with someone online who was upset that I shared a post that they didn’t agree with on Instagram. In one of their replies to me, the phrase “Christianity is what our Country was founded on, we have completely turned from that…” caught my attention. I had just spent several intensive days taking a close look at the Constitution and the First Amendment, which laid out faith freedom for all as a central idea, not faith freedom for one particular faith tradition. This person was letting me know that as a Christian, they felt I was wrong in sharing a post that didn’t align with their stance. They thought that as a Christian, I should want everything in our nation and government to be centered around Christianity, but I don’t share that view.

This online conversation was my opportunity to practice respectfully speaking up about matters in which we thought differently. So, using my chaplaincy and spiritual direction interpersonal skills alongside information from the BJC Fellows Seminar, I crafted a response that acknowledged this person’s feelings of concern while sharing that I disagreed, but I left the door open for future conversations.

I shared about this experience with our BJC Fellows group, and my peers felt I modeled well how to have tense one-on-one conversations. I also heard some say that they would not have engaged that person, but I found myself declaring, “No, we need to be open to having conversations with people who think differently than us. Otherwise, how can any change take place?”

The location of the BJC Fellows Seminar was an immersive experience located right next to a key site in our nation’s history. Colonial Williamsburg’s mission – “that the future may learn from the past” was experienced repeatedly, but also specifically when I happened upon a certain sign. I was waiting next to a market, and I saw a sign posted — next to the benches, on a wooden barrel — that said, “Auctions held most Saturdays.” (see photo) Why was that there? What does that mean? I don’t know about you, but for me, I saw that sign and immediately thought they were auctioning people. They are auctioning slaves. “Why was this sign here?” I wondered. I’m glad that it was there and that I saw it, but I also wish it were never there. I ended up pointing it out to my BJC Fellows peers without giving them any context, and I watched them as they experienced similar reactions.

There’s nothing surprising about the reality of slave-owning in the history of the United States. It is a grim reality of our past. But I didn’t expect to see that sign right in front me standing there as a quiet witness. During our week in Colonial Williamsburg, I remembered hearing peers share that one of the house guides informed them that the wife’s bedroom was facing towards the back to oversee the slaves that worked for their household. This was the reality of life back then and because we had so much conversation about different narratives in the BJC Fellows Seminar, I was acutely aware of what had always been there, but I didn’t see it fully when I first visited Colonial Williamsburg many years ago.

When two peers from the BJC Fellows Seminar joined me in an Uber to the Richmond airport, the driver nonchalantly asked us why we were in Williamsburg, mentioning that he grew up there. I shared with him about the sign and asked him what he thought they were auctioning. “Colonial furniture,” he stated, matter-of-factly. (I should mention that the driver was white and all three of us passengers were non-white.) I replied that I had not thought of that; for me, when I saw that sign — as a minority race female that grew up in the South — I thought it meant they were selling slaves. I also talked about our BJC Fellows experience in Williamsburg, learning about faith freedom for all, including how several writers of the U.S. Constitution made sure to include faith freedom in the founding documents, even though they owned people as slaves.

So, on that final day, as we were leaving, I was curious what the driver thought about that sign. I recognized that, perhaps like me before, he wasn’t thinking about other narratives of what that sign could mean, to which he admitted “that wasn’t [his] context.” I also sensed that he was open to hearing more about my own experience (or was I courageously stepping into education and advocacy work?).

Some might react defensively to topics sensitive to them, like the person on Instagram, but others may be open to dialogue and hearing other people’s views. Suppressing conversation, especially on difficult topics or when people are expressing emotion, hinders our ability for all of us as a people, and us as a nation, to learn, develop and grow.

I was extremely comfortable throughout this brief conversation. But once we arrived at the airport, one peer expressed concern that I would even bring up the subject of race or slavery, potentially sensitive topics, to a person that is white. I realized that our past or other’s past or present negative experiences can cause us to feel unsafe and shy away from potential experiences and interactions that could be enlightening (or can go awry). But just like my earlier interaction on Instagram, we can choose to be open enough to engage others with empathy and curiosity to see their point of view. Thinking about our situation further, I realize that one BJC peer had the posture of a peacemaker and the other had the posture of a bystander. One felt it was unsafe to discuss sensitive topics and so intentionally changed the subject while the other was quietly waiting to see how this conversation was going to turn out. Even the Instagram conversation was with someone who felt like their beliefs and values were being threatened, especially by someone who shared the same faith. All these different responses are common and ones that I have operated from as well. But what was surprising to me in Colonial Williamsburg was how I had already moved courageously towards taking positive actions in advocacy work.

I’ve become very aware of other narratives and perspectives that were also very much a part of our history. Today, there are other voices too, perhaps standing as silent witnesses waiting to be seen.

Toward a new religious freedom in Colonial Williamsburg

By Rev. Dr. Corey D.B. Walker

Walking the streets of Colonial Williamsburg, one cannot help but be captured by the colonial panorama on display. History and imagination combine to extend an invitation to creatively revisit a day in the life of colonial America. Yet, Colonial Williamsburg is “the world’s largest living history museum.” As such, it conveys multiple narratives about the past and is also very much a product of the present. It is this quality that makes Colonial Williamsburg such an interesting site for the annual BJC Fellows Seminar.

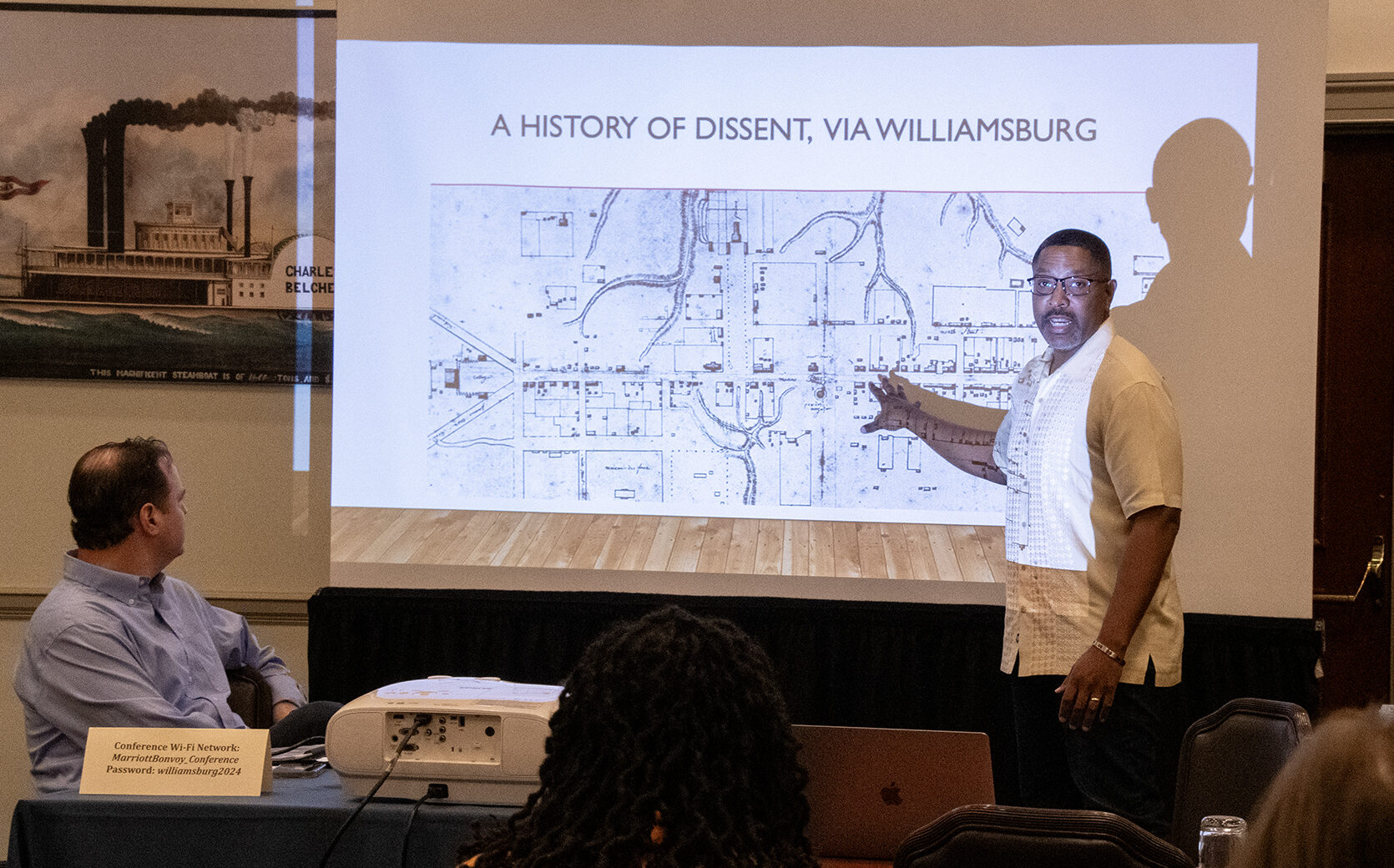

In 2019, the Rev. Dr. Nathan Taylor and I came together to develop a novel tour of Colonial Williamsburg for the BJC Fellows. Nathan is executive director of the Virginia Baptist Historical Society with a deep knowledge of Baptist history in Virginia. Five years later, we reprised our tour for the 2024 BJC Fellows Seminar. The prosaic title of our tour, “A Baptist History of Dissent,” takes on multiple meanings as we reimagine the geography of Colonial Williamsburg as a geography of religious freedom. The tour is one where questions are welcomed, openness is valued, and closed, totalizing answers are eschewed.

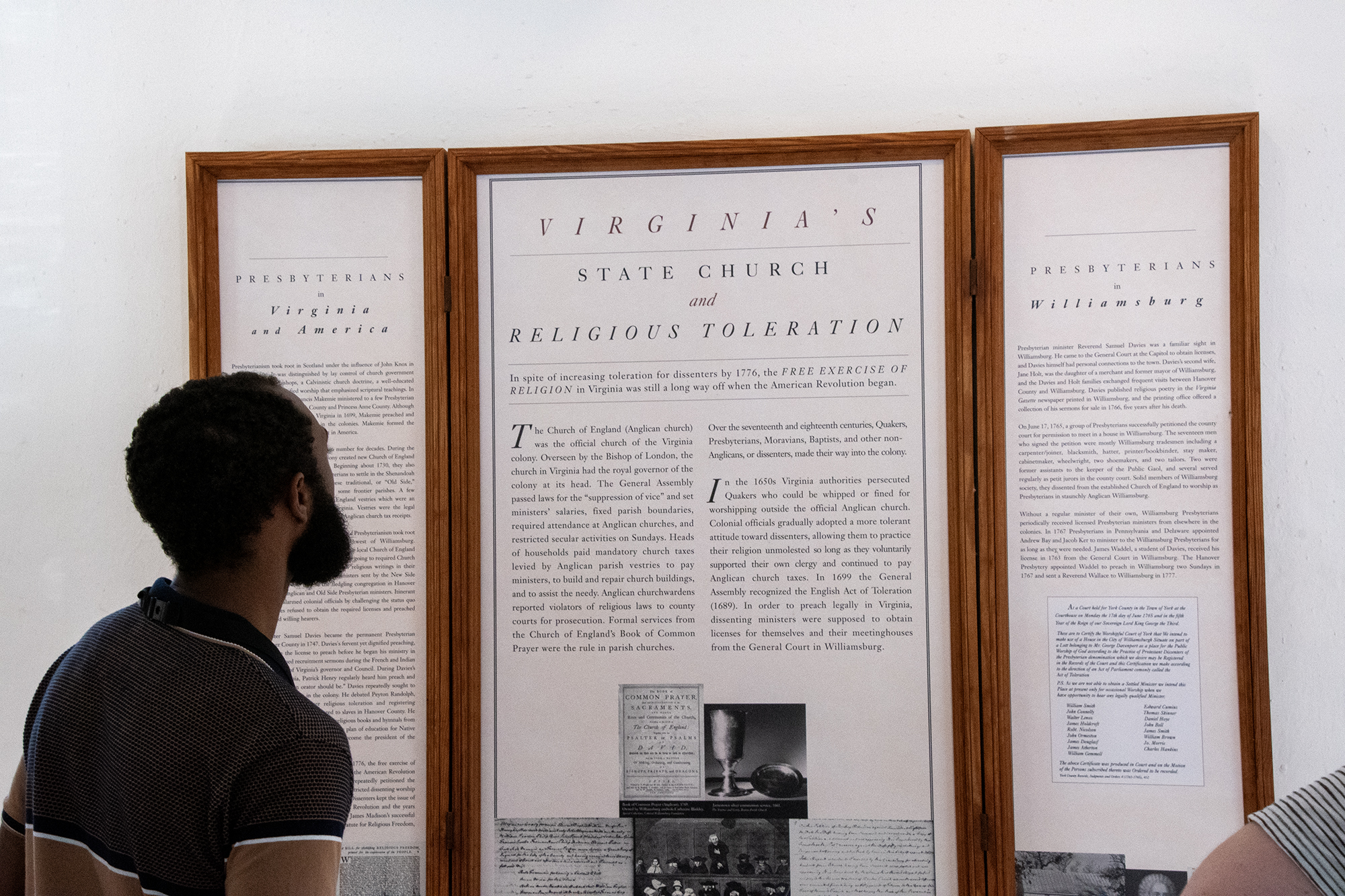

The Capitol Building and the Public Gaol not only represent law and order, they also represent the struggles for religious liberty and the limits of religious dissent. The Raleigh Tavern and the King’s Arms Tavern emerge as distinctive spaces of a new commons where public discussions of liberty, including religious liberty, were daily fare. The home of Robert Carter and Bruton Parish Church are key sites where the existence of freedom and slavery mark the limits of traditional narratives of religious freedom. Colonial Williamsburg crystallizes a complex and complicated past that exists as a living legacy in our contemporary moment. That is what makes this living history museum an exemplary classroom for exploring the multiple histories of religious freedom in America.

Colonial Williamsburg is a prescient reminder that there is no single “real” history of colonial America or “real” story of religious freedom. The BJC Fellows come to critically recognize this important point as they walk the streets of this living museum. They learn that interpretations of the past are influenced by our constructions of the past and by the contingencies of the present. And they become cartographers of new geographies of religious freedom that is not “out there” waiting to be discovered in some pristine state. Rather, it is always in a process of becoming as we continue this grand experiment of democracy in America.

Rev. Dr. Corey D. B. Walker is Dean of Wake Forest University School of Divinity and Wake Forest Professor of the Humanities at Wake Forest University. He also serves as a member of the advisory council of the BJC Center for Faith, Justice and Reconciliation.

Interested in being a BJC Fellow?

There is no religious requirement for the program, and applications open each winter.