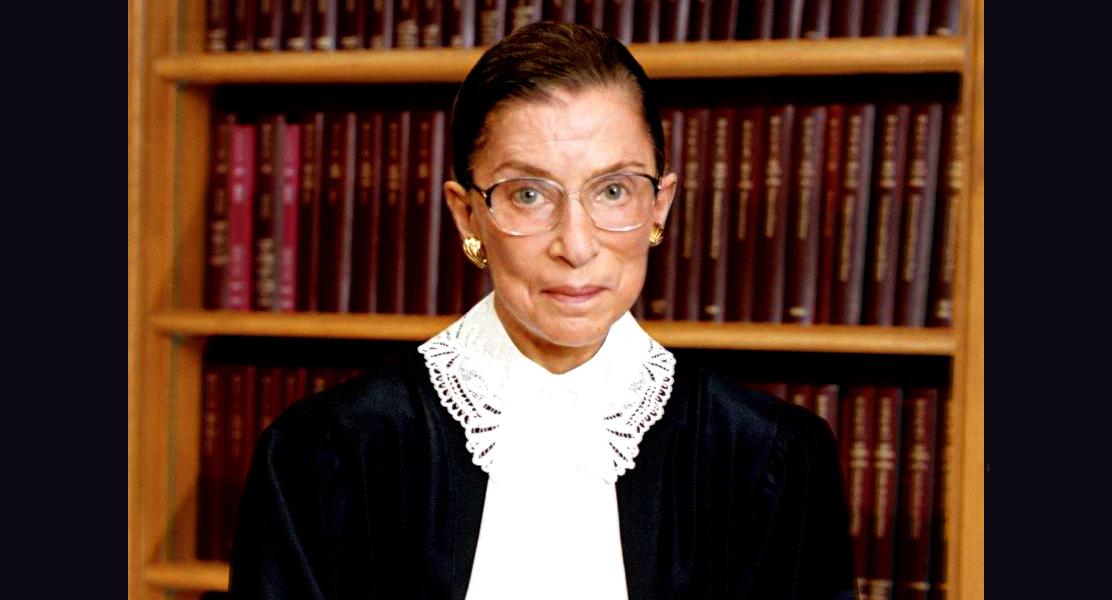

BJC on the legacy of Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Before we all get caught up in the rush to confirm a new Supreme Court justice, it is worth a breath and a moment of pause for some thoughtful reflection on the religious liberty legacy of the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. BJC Executive Director Amanda Tyler and General Counsel Holly Hollman have done just that in two brief essays I highly recommend.

Writing for Baptist News Global, Hollman mixes legal insights with personal reflections, including her memory of observing an oral argument in which Justice Ginsburg referenced a BJC amicus brief:

I was seated in the lawyer’s section of the Supreme Court … during oral arguments in the two cases that challenged government-sponsored displays of the Ten Commandments. BJC had long been a leader in opposing such displays, which tend to show government preference for religious majorities and ultimately harm religion. I felt the eyes of my colleagues turn to see my face when Justice Ginsburg pointed to an approach offered in “the Baptist brief” as she questioned the oral advocates. Our approach suggested that the court adopt a presumption that a government that sponsored a religious display endorsed the message of that display. The approach recognized that government-sponsored religious displays tend to violate the neutrality toward religion that the Constitution demands.

While the court did not adopt our proposed rule in those cases, I remain proud that Justice Ginsburg recognized our advocacy to protect religious liberty by avoiding government-sponsored religion.

Hollman and Tyler collaborated on another essay for The Christian Citizen, evaluating Justice Ginsburg’s religious liberty record. Her support of both the Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clauses, they write, left a voting record that “historic Baptists applaud.” The piece also details one of Justice Ginsburg’s signature religious liberty contributions, her majority opinion in Cutter v. Wilkinson (2005) upholding the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA).

Justice Ginsburg wrote that, most importantly, the accommodation in RLUIPA was designed to relieve exceptional burdens imposed by the government. The law covers “state-run institutions—mental hospitals, prisons, and the like—in which the government exerts a degree of control unparalleled in civilian society and severely disabling to private religious exercise.”

The opinion specifically noted that, when applied properly, RLUIPA should take account of the burdens a requested religious accommodation may impose on other individuals and other essential governmental interests, such as an institution’s need to maintain order and safety. As Ginsburg’s opinion stated: “Our decisions indicate that an accommodation must be measured so that it does not override other significant interests.”

The debate over how courts should “take account” of the impact an accommodation would have on other individuals and government interests continues to be challenge litigants and judges, from COVID cases to the contraceptive mandate to foster parent placement, an issue the U.S. Supreme Court is scheduled to hear in November (Fulton v. City of Philadelphia). Justice Ginsburg’s measured approach to addressing the demands of that critical balance – as much as her fiery dissents – will be missed.