S6, Ep. 03: On the road with ‘How to End Christian Nationalism’

Hear a conversation about Christian nationalism, recorded live in North Carolina

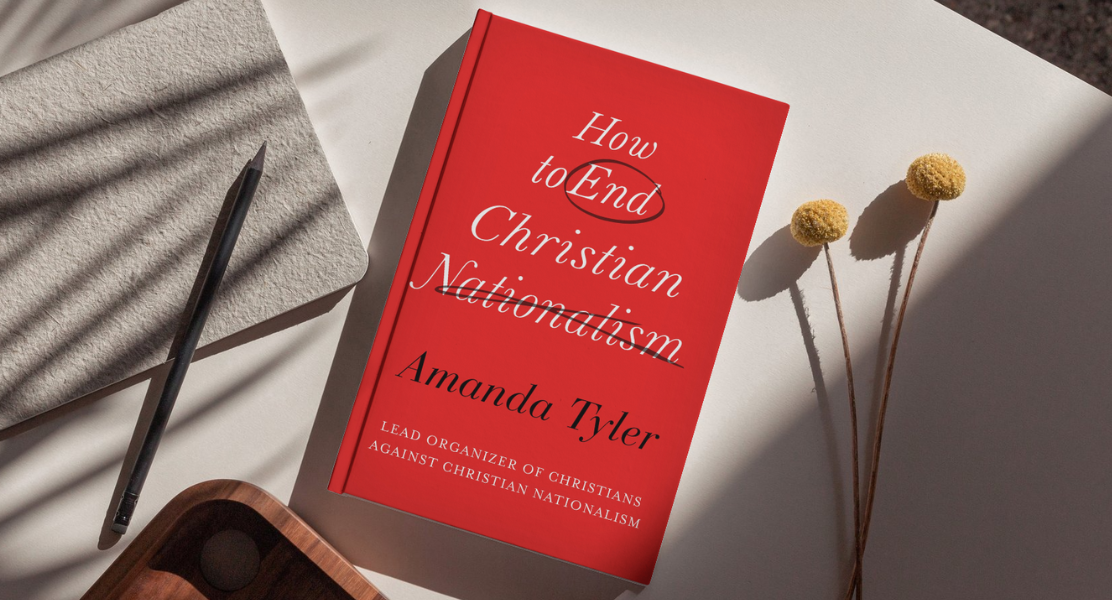

Today’s episode takes you on the road with Amanda Tyler as she travels the country with her book, titled “How to End Christian Nationalism.” You’ll hear a conversation with Amanda and the Rev. Dr. Bill Leonard about the problems of Christian nationalism, held October 29 at Knollwood Baptist Church in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. “How to End Christian Nationalism” is a vital companion for countering the dangerous ideology, and you can order a copy wherever you get your books.

Our next podcast episode will be released November 21, and it will include Amanda’s and Holly’s reactions to the 2024 elections.

SHOW NOTES

Segment 1 (starting at 00:37): Today’s show

You can order Amanda’s book wherever you get your books. Visit EndChristianNationalism.com for more information and a list of upcoming tour dates.

The Rev. Dr. Bill Leonard is the founding dean at the Wake Forest University School of Divinity, who now holds the title of “professor of divinity emeritus.” He has written some 25 books, and his research focuses on Church History with particular attention to American religion, Baptist studies, and the Appalachian religion. Learn more about him at this link.

Dr. Leonard was a guest on our 2019 podcast series about the dangers of Christian nationalism, featured on the episode addressing the misguided idea that America was founded as a “Christian nation.” Listen to that episode at this link.

Segment 2 (starting at 02:36): The conversation

You can watch a video recording of this conversation on the YouTube page of Knollwood Baptist Church.

This event was a partnership between Knollwood Baptist Church, First Baptist on Fifth, and Ardmore Baptist Church, all churches located in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Segment 3 (starting at 47:45): We’ll see you in two weeks for our election episode!

Respecting Religion is made possible by BJC’s generous donors. You can support these conversations with a gift to BJC.

Transcript: Season 6, Episode 03: On the road with How to End Christian Nationalism (some parts of this transcript have been edited for clarity)

AMANDA: I really call them the “Charlton Heston Ten Commandments,” because that particular version is the version that’s on some of those big monuments that are around the country that were put there to publicize the movie “The Ten Commandments.”

Segment 1: Today’s show (starting at 00:37)

AMANDA: Welcome to Respecting Religion, a BJC podcast series where we look at religion, the law, and what’s at stake for faith freedom today. I’m Amanda Tyler, executive director of BJC.

HOLLY: And I’m general counsel Holly Hollman. Today’s show is being released on Thursday, November 7, just two days after Election Day in our country. We recorded today’s program before the election, and our next episode, which will be coming out November 21, will include our reactions to the elections.

AMANDA: But before then, I know we have talked a bit about my new book, How to End Christian Nationalism, and today’s show will be taking you with me on the road. We will be playing audio from a recent book tour event in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, which was recorded on October 29 at Knollwood Baptist Church.

HOLLY: Yes. You were in conversation with our dear friend Rev. Dr. Bill Leonard for this event in a place that I am very fond of. Dr. Leonard is a longtime friend and partner of BJC, and he’s the founding dean at the Wake Forest University School of Divinity, who now holds the title of Professor of Divinity Emeritus.

He has written some 25 books, and his research focuses on church history, with particular attention to American religion, Baptist studies, and Appalachian religion. He has inspired generations of young seminarians and others to think about religion and religious liberty, and we call on him often.

AMANDA: We do. And, in fact, we at BJC have worked with Dr. Leonard a great deal over the years, and I had the opportunity to interview him for our podcast series about the dangers of Christian nationalism back in 2019. He was featured on our episode that drilled down on the misguided idea that America was founded as a, quote/unquote, Christian nation. We’ll put a link to that episode in the show notes.

HOLLY: I’m excited to hear this conversation you had with Dr. Leonard, so let’s play it now.

Segment 2: The conversation (Starting at 02:36)

REV. DR. LEONARD: Amanda, at the beginning of the book, you define Christian nationalism and the myth of America as a Christian nation. Please talk with us about what that involves and where that is taking us now.

AMANDA: Yeah. Well, thank you so much, and thanks to all of you for being here tonight. I always think it’s important to start with definitions —

REV. DR. LEONARD: Uh-huh.

AMANDA: — because especially on a topic as charged, complicated and misunderstood as Christian nationalism.

So Christian nationalism is a political ideology and a cultural framework that tries to merge American and Christian identities, and it’s a subset of a larger phenomenon of religious nationalism, which has been a recurrent problem throughout history and around the world today.

And, you know, American exceptionalism — this other idea that there’s something special, unique and different about the United States’ story — that’s part of Christian nationalism. But when it comes to Christian nationalism, America’s not — and religious nationalism in particular — America’s not unique. America’s not exceptional. Right?

But the particular brand of Christian nationalism in the United States’ context, I think, does have some particular aspects to it. And so while I want us to think about a global religious nationalism, I think just to kind of put it into context, much of what we discuss tonight, I think, is going to be about American Christian nationalism.

So American Christian nationalism also suggests that to be a real American, a true American, one has to be a Christian, and not just any kind of Christian but a Christian who holds fundamentalist religious beliefs that are in line with certain conservative political priorities.

And so I think it’s important to note, Christian nationalism is not just an ideology and a framework, but also a highly organized political movement that is gaining force at this particular time.

Christian nationalism is also a very old problem. You know, in the world context, I think we can date Christian nationalism all the way back to Constantine —

REV. DR. LEONARD: Yeah.

AMANDA: — the first time that an empire took the religion of Christianity on as its own and then used all the force of that empire to impose the religion on everyone else, often through violent means and through creating systems of “us versus them,” which is also a key part of what breeds Christian nationalism.

But as the name suggests, Christian nationalism also relies heavily on this mythological founding of the United States as a quote/unquote “Christian nation,” not in a demographic sense but rather in a sense that it was founded by Christians in order to privilege Christianity in law and policy.

It also has a heavy emphasis on the idea that God’s providential hand is guiding America through history, that God has a special role for the United States in God’s plan for the world, that God loves America best. God bless America. Right?

So there are aspects of civil religion that also overlap with Christian nationalism, and it’s problematic for a number of reasons, some of them theological. You know, the Gospel of John says in its most quoted and memorized verse, “For God so loved the world.” It doesn’t say, “For God so loved the United States.” But that’s the story that Christian nationalism tells.

And then, of course, it’s also problematic because it doesn’t align with a more honest and fulsome reading of American history, particularly constitutional history, because the framers of the U.S. Constitution made a very deliberate choice to disestablish religion from government, learning from the colonial past and the problems with established religion, problems for democracy, yes, but also problems for religion itself.

And so they made a choice in the founding document, the U.S. Constitution — which is a secular document — to separate the institutions of religion and government, to, in fact, make sure we did not have a Christian nation in the sense that that’s often talked about, but rather a religious freedom nation, a nation where one’s belonging would not depend on one’s religious identity or how one worships, the problem, of course, being that that promise, that constitutional promise of religious freedom for all has not been fully realized, in part because of the recurrence and the staying power of this ideology of Christian nationalism.

REV. DR. LEONARD: Those who came to this country often spoke, many of the Puritans particularly who came to New England — there was an established church among Anglicans in Virginia and in the South and among the Puritans, particularly in Massachusetts and New England, and they often spoke of the land to which they had come with such terms as “redeemer nation,” “God’s new Israel,” “chosen nation.” And that got passed on extensively through a variety of particularly Protestant denominations. So many of the early colonies were, in themselves, little religious establishments that were essentially — or tried to be — theocracies.

That leads us to another question. Christian nationalism is often referred to as “white Christian nationalism.” And so race is in many ways inseparable from the Christian nationalist mentality, particularly in the early days of America with slavery and the way in which many — particularly Southerners — used the Bible to defend that practice. But now in many ways, it’s focused on immigrants. Talk about that as you pursue it in the book.

AMANDA: Yeah. So I think it’s absolutely critical that we talk about how Christian nationalism overlaps with white supremacy. And I really — you know, and writing the book comes out of more than five years of leadership of the Christians Against Christian Nationalism campaign, talking about Christian nationalism in all kinds of groups.

And when we started the campaign, we started it with a statement in the kind of central piece of Christians Against Christian Nationalism that says, “Christian nationalism often overlaps with and provides cover for white supremacy and racial subjugation.”

And when I first started writing the book, I had a separate chapter that was just about white supremacy and racism. And you won’t find that chapter in here anymore, because as I wrote it, I thought, this is running through the entire understanding of what Christian nationalism is. It’s not a discrete piece of it. It’s completely part of what American Christian nationalism is.

In the book I also talk with and interview a number of different people who are working on the issue, and one of them is a scholar of religion and religious history, Dr. Anthea Butler, who’s at the University of Pennsylvania. And I asked her the question in the book, you know: How do you see that Christian nationalism overlaps with white supremacy or provides cover for white supremacy?

And she paused, and I write about this piece, and I started to get nervous. And I said, Well, do you see that? And she said, Not really. She said, I think for those of us who are Black, we see it as a signpost at the door. We don’t see that it provides cover. We just see it as white supremacy in American Christianity.

I included kind of my own awakening in that moment in the book, because I think it shows that particularly as white Christians, we are continuing to wake up to our own privilege in this area, how we have been privileged by white Christian nationalism in this country in ways that are sometimes hard for us even to understand, even those of us who are actively working to dismantle it.

And so how I understand it is — and it goes back to this history — is that that mythology of America as a Christian nation, it also says that the only people who are really worthy of full citizenship rights in this country are the same people who held power at the beginning of the country, the same people who were granted those full citizenship rights in the original Constitution, which were really white, Protestant, Christian men who owned property.

Those were the only people who were full Americans at the beginning, and everyone else had some lesser citizenship status accordingly. Some people had no rights, of course, and were held as property as enslaved people.

And so we have to understand that that has an effect on a people. Those roots of our history have really meant that we are still dealing, if we are brave enough, we are still dealing with the repercussions of that today. And so to really face white Christian nationalism, we also have to face the racism that’s inherent.

And that gets — I mean, talk about a current issue. Two nights ago, we watched a rally at Madison Square Garden which talked about Americans as “garbage,” which talked about having migrants kicked out of the country. We’re talking about people in ways that are dehumanizing and are all loaded with all kinds of coded racist language, xenophobic language, and that is being propagated, in part, by reliance on Christian language, Christian symbols, with Christianity itself.

And this isn’t a new problem. You know, just as you talked about the Puritans, our ancestors in the faith allowed their theology to be misused, abused, distorted out of recognition in service of power in the past.

A doctrine of discovery, which is this deadly heresy and was this deadly heresy that it was God’s will for European conquerors to steal this land from Native peoples, that was when we first started seeing this seeping Christian nationalism infect our American Christianity in ways that have pulled us away from the teachings of Jesus, and we have to reckon with that as we face the modern implications, including the abject racism and othering that we’re seeing in our modern discourse.

REV. DR. LEONARD: Thomas Dixon, a graduate of Wake Forest College, Baptist minister, writes two books in the early 20th century, one called The Leopard’s Spots and the other called The Clansman, which became a text for the infamous movie, “The Birth of a Nation,” and he ties white supremacy to the KKK —

AMANDA: Right.

REV. DR. LEONARD: — and the need under God to resist what he calls “mulatto Christianity,” meaning interracial Christianity, as opposed to thoroughly white biology.

So it’s a long history in the country.

Amanda, you had a quote that just jumped out at me around chapter 7 or so, and I’ll read it tonight.

“By merging the almighty power of God with the earthly power of the state, we reduce the sacred to the secular. When an empire claims for itself the mantle of sacred legitimacy, Christians must confront it by speaking the truth to power.”

Elaborate on that amazing and very important quote.

AMANDA: Well, I think this was the chapter where I’m really encouraging people to take an active place in the public square and giving examples of how some of our political leaders have confused their callings in the public square to serve all people in our democracy who have elected them with some kind of religious ordination. Right?

And the example that I give is the current speaker of the House, Mike Johnson. I just happened, pure coincidence, to be testifying on Capitol Hill the day that he was sworn in and took over leadership as Speaker of the House. And so I was watching very intently that day when he gave his speech.

And in his speech, accepting — really assuming that leadership role to be second in line to the presidency, to lead the most democratic institution that we have in this country in the U.S. House of Representatives, he said that it was his belief that every person in that chamber had been ordained to their position by God.

And in that moment, he tried to take what was a secular, democratic institution and turn it into a religious one, and he violated, I believe, the free and fair votes of every American who were voting for their rights to be represented there and not to be part of a religious body.

He also violated the religious freedom rights of the elected officials sitting in that place, not all of whom share his belief that they were ordained by God to serve in some religious role in that place.

And so I think it is so incumbent on all Americans to be actively involved in the democratic process that we have here, and that for those of us who are people of faith, whatever faith tradition that is, that we bring our faith to bear in our public advocacy in ways that Dr. [James] Dunn would have told us to do as well, but that we do it in ways that don’t insist that our positions be reflected in law and policy.

We aren’t about setting up a theocracy that just happens to be how we would run things. We are about advocating for a pluralistic democracy that represents everyone’s interests, regardless of religion, and we can exercise the full limits of our religious freedom rights by making sure that our religion is animating the work that we do in the public square.

But we have to be careful about the ways that we talk about the work that we’re doing. I get uncomfortable, I will say, when I hear about our rights as Americans being called “sacred” rights. I think we’re sometimes a little fast and loose with the language — our religious language when we’re talking about our democratic rights as Americans, in ways that can be confusing. Right?

And so I want to point out an example like Speaker Johnson saying, you know, we’re all ordained to these positions. But I also think we need to be careful when we’re talking about our voting rights, which are absolutely fundamental to the democracy, but not call them “sacred” rights in ways that might be confusing about what we’re actually about when we’re doing the people’s business in a pluralistic democracy.

REV. DR. LEONARD: I would simply add to that that from my perspective, one of the major reasons that has fueled Christian nationalism is the decline of particularly Protestant privilege in the country and where the changing sociology of Sunday has created a great deal of concern among certain groups of Christians because fewer and fewer people are attending church in general or attending, even for people regularly participating in church, attending intermittently. And COVID didn’t help with that.

AMANDA: Yeah.

REV. DR. LEONARD: And so reaching out to the state to protect what the culture used to protect in certain ways and feeling that loss contributes, I think, to many of the things that you’ve been talking about.

AMANDA: Oh, absolutely. And I would say that that impulse, that kind of self-preservation impulse and an impulse that comes out of a sense of scarcity, certainly not an abundance — it’s not an abundant impulse there — it actually is completely counterproductive.

And I talk with some actual data in the book about when you look around the world today — I mean, we can talk about history and about the fact that religious observance at the time of the founding was actually quite low, because we were coming out of a period of established religion. Guess what. When people are forced to go to church, they don’t really want to go very much when they’re given the choice.

And so we can learn from history, but we can also look around the world today and see examples where places do have established religion and their actual rates of religious observance and religious belief, as far as they can measure it, are lower than in places that don’t have established religion. So their own efforts at self-preservation will be self-defeating in the end if they get their way.

REV. DR. LEONARD: And your last point is extremely important in terms of thinking that that will increase church participation, when actually it declines from that, which brings us to church-state separation, long a theme and focus of the Baptist Joint Committee. And I think it’s important for you to lay out, as you do in the book, the meaning of church-state separation within the context of religious liberty and the First Amendment.

AMANDA: So I do have a whole chapter on defending the separation of church and state, and understanding what it is and how it protects religious freedom because it is so misunderstood.

I’m really not trying to pick on Speaker Johnson, but I will say that he has been a very loud proponent — and as he claims the mantle of being a constitutional lawyer, he says basically that church-state separation doesn’t exist. Some of his colleagues have said the same thing.

And, in fact, it does exist, and it is an incredibly important way to protect everyone’s religious freedom. So in our constitutional system, we started with just the U.S. Constitution itself, and the U.S. Constitution makes no mention of God, makes no mention of “Christian” or Jesus, and its only mention of religion is in Article VI which prohibits religious tests for public office.

So my favorite rebuttal to people who claim that America is a Christian nation is to say, you know, the Framers of the Constitution were really brilliant men, and if they wanted to create a Christian nation, this is about the most ineffective way I could possibly think of them creating a Christian nation, since they —

REV. DR. LEONARD: (Laughing.)

AMANDA: — from the very beginning, there will be no religious test for public office, because, of course, that’s not what they were creating.

They were creating a secular government in which religion would be left for the people to determine and for the people to support the religious houses of worship and other religious institutions.

And then, of course, four years after the U.S. Constitution, we have the Bill of Rights, and there was concern that religious freedom was not sufficiently protected under the new U.S. Constitution. And so the first 16 words of the First Amendment are “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Of course, freedom of religion is the first of five freedoms that are protected in the First Amendment, but religious freedom is protected by two clauses, the No Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause. And this arrangement is what goes by the shorthand “separation of church and state.”

Now, naysayers will say, separation of church and state’s not in the U.S. Constitution. Well, neither is separation of powers. Right? Those words, “separation of powers,” are not in the U.S. Constitution, but that’s what the whole framework does. In the same way, the First Amendment sets up a framework of the separation of church and state that is protected by these two clauses.

And so in the book I give examples from the founding period that that is, indeed, how the Framers and the people at the time and even Alexis de Tocqueville, who came and, of course, wrote his famous book Democracy in America, that everyone at the time knew it as separation of church and state. This is not some liberal creation of the last 50 years.

But we know that this separation of church and state has never been absolute. We have always had the involvement of religious people in our democracy, and I argue that that’s a very good thing. You know, we don’t have like a French system which decides to separate religion and government to such an extent that religious language and religious participation is really shunned from the public square.

Rather, we have a robust religious sector that engages, you know, continually in the public square. But that does make it incumbent on all of us to be sure that the Christian majority, the Christian privilege, the Christian supremacy, frankly, that we have in our culture does not overtake the rest of the religious life in this country to such an extent that we undercut that founding promise that belonging in the United States would never depend on one’s religious identity.

I think that that is the ideal that is included in the U.S. Constitution, but it’s an ideal that we have fully yet to realize, and so we have to, as we think about the ways that religion and government relate to one another, we have to be mindful, I think, of that being our goal.

And another piece of this that I do write about is that the question cannot be simply, Is it constitutional? I think that that — we’ve gotten to a point in this country that we think anything that’s constitutional is a good idea, and that’s simply not the case.

As a lawyer, I can tell you, the law is often the lowest common denominator. Right? If we only go about doing what’s legal and not asking ourselves, Is this the right thing to do, then we’re not going to want to live in this society much longer, particularly when the U.S. Supreme Court continues to, I believe, misinterpret the First Amendment in ways that have expanded the Free Exercise Clause, diminish the No Establishment Clause in ways that are really undercutting religious freedom for all people.

REV. DR. LEONARD: That’s wonderfully stated. You and I both admire very, very greatly the colonial preacher Roger Williams who came to this country in 1630 as a Puritan preacher but was very quickly thrown out of Christian nationalist Massachusetts because he said several things.

One, he said, the Native Americans are the sole owners of the American land and should be justly compensated for it. Could I get an “Amen” for that?

AMANDA: Amen!

AUDIENCE: Amen! (Applause.)

REV. DR. LEONARD: Secondly, he said, there are no Christian nations, only Christian people, bound to Christ, not by citizenship but by faith.

The Baptists can say “Amen” to that here tonight, at least.

AMANDA: Yeah.

REV. DR. LEONARD: And, third, he said, contrary to popular opinion, Jews and what he called “Turks,” meaning Muslims, make fine neighbors, like everybody else does, and should not be punished for their religious belief.

And he particularly wanted to be clear that God alone is judge of conscience, and neither the state or an official established church can judge the conscience of the heretic, the people who believe the wrong stuff, or the atheist, the people who believe not at all in a particular religion.

This is — and he lived for a time — he invented Providence, Rhode Island, after the Puritans threw him out, and for a time, he lived with the Native Americans and bought land from the Narragansetts and wrote the first treatise on the Native American language called, A Key into the Language of America, in 1640, and he writes much of it in verse.

And I couldn’t go without sharing this, my favorite part of the verse. “When Indians see the lying ways of cruel English men, their taunting notes their murders great. Then say these Indians then, We wear no clothes, have many gods, and yet our sins are less. You are barbarians, pagans wild. Your land’s the wilderness.”

AMANDA: Uh-huh.

REV. DR. LEONARD: How did Roger Williams in 1640 see what some of our relatives and friends and politicians in America can’t see 400 years later?

AMANDA: Uh-huh.

REV. DR. LEONARD: Christian nationalism and the public schools.

AUDIENCE: (Murmuring.)

REV. DR. LEONARD: Yeah. Ten Commandments on the walls of schools, every school in Louisiana, but now they’re having to put asterisks by, “Thou shalt not give false witness.”

(General laughter.)

REV. DR. LEONARD: And every public school teacher in Oklahoma, required to be able to teach a class in Bible.

Talk about Christian nationalism in public schools, Amanda.

AMANDA: So those two examples were too late for me to include in my book, but I do have an entire chapter — you know, we can talk about how Christian nationalism is infecting and impacting a lot of different public policy issues, but I chose public schools to focus on, one, because they impact everyone.

Now, whether or not you have kids or grandkids in public schools now, 90 percent of America’s children are educated in public schools. This is our future of our country, and of course, our tax dollars support them as well. So we all have a stake in what’s happening in America’s public schools.

Two, there is a concerted effort by the movement of Christian nationalism to target public schools with these policies, and that’s because the public polling shows people aren’t born with the ideas of Christian nationalism. They have to be indoctrinated into them. And so there is a particular effort to push this in public schools, in part for the very reason you said earlier, the idea being, well, if they’re not going to go to church on Sunday, we’ll just make sure they get Bible Monday through Friday in the public schools.

And so we have efforts that started several years ago, first with just the posting of, “In God We Trust” in public schools. In God We Trust is the national motto, but it’s only been the national motto since the 1950s, which was a prior high tide of Christian nationalism during McCarthyism and all of those early days of the Cold War, the same period when “under God” was added to the Pledge of Allegiance, examples of civil religion, again, that just lead to this kind of constant hum of Christian nationalism, this daily reminder in our heads that to be an American means to be a Christian.

Often they have window dressing of inclusion by saying it’s all about Judeo-Christian values, but just hear how in trying to appear inclusive, they’re actually being quite antisemitic in the process, because there is no such thing as a Judeo-Christian religion. They’re reducing Judaism to just a modifier of Christianity. It is another form of Christian supremacy to even talk about Judeo-Christian values.

But this is the false rationale that they give for things like the posting of the Ten Commandments. You know, I have no problem with the Ten Commandments. I just don’t think they should be posted in public schools or taught in public schools the way that they’re being taught here, because the rationale, they say, is that the Ten Commandments is the basis of all American law.

Have you heard that before? The Ten — that is not true. Right? They just keep saying it over and over again to the point that it sounds true. Right? But that’s what we will hear as the reason, that one can’t be a good American citizen if one doesn’t know the Ten Commandments.

I agree that the Ten Commandments are a good set of rules to orient our lives by, but they are not contingent upon being a good American citizen, to know the Ten Commandments, particularly not the official government version of the Ten Commandments, which is, by the way, an edited version of the King James Bible that came out —

I really call them the Charlton Heston Ten Commandments, because that particular version is the version that’s on some of those big monuments that are around the country, that were put there by a fraternal order to publicize the movie “The Ten Commandments” in the 1950s.

REV. DR. LEONARD: Wow.

AMANDA: Right? So in 1960s. So Hollywood is involved in all of this, but a lot of people don’t know that. And that’s, again, the problem, the problem being not just this signal that’s being sent, sometimes in ways that are not at all subtle to America’s children, that they don’t fully belong if they don’t have a given religious identity, in ways that really interfere with these kids’ religious freedom rights and the religious freedom rights of their families, but also in the way that our religion is being — a particular version of religion is being assumed as the official religion by the U.S. government, an idea that was firmly rejected in the founding document of this country in ways that we would not establish religion. We are literally going backwards when we’re doing these projects.

But you talk also about what’s happening in Oklahoma. There the state superintendent of education, Ryan Walters, this summer issued an edict, and we talked about this on our podcast previously. It was days after Louisiana signed their law that they would have the Ten Commandments. They didn’t want to be one-upped by Louisiana, so the edict literally reads, We will teach the Bible, comma, which includes the Ten Commandments, in case anybody didn’t know.

We’re teaching Ten Commandments, too, in Oklahoma, but we’re going to teach it by requiring that every public school classroom have a Bible and that teachers teach out of the Bible in courses like history and civics, because, they say, you can’t understand the U.S. Constitution without understanding the Bible. Again, a secular document, no mention of the Bible, no mention of Christianity, and so again sending this signal of full belonging.

And then as we’ve come to find out, the Bibles that they are instructing be bought are not just any Bibles but a King James version of the Bible that includes the founding documents in the Bible themselves. So this is textbook, literally textbook Christian nationalism, this thorough merging of American and Christian identities.

And as it turns out, there was exactly one Bible that met those specifications, something called the God Bless the USA Bible, which was the only Bible endorsed by President Trump, which I said, you know, when we talked about this previously, I said, you know, I don’t think the Bible needs anyone’s endorsement.

(General laughter.)

AMANDA: But it’s not only endorsed by Trump, but he personally receives royalties on every Bible that’s sold. So we see this really cynical undercurrent of personal profit motive that’s also driving some of these policies.

REV. DR. LEONARD: October 31 is the 507th-year anniversary of the Protestant Reformation. What you’ve just explained is why the selling of indulgences ain’t over yet.

AMANDA: Yeah.

(General laughter.)

REV. DR. LEONARD: How’s our time? Five minutes. I was going to ask you to talk about Jesus, but that’s not enough time.

(General laughter.)

REV. DR. LEONARD: Really quickly – [looking offstage] Oh, with Jesus we can get ten minutes?

AMANDA: (Laughing.)

(Applause.)

REV. DR. LEONARD: Oh, that’s wonderful. I tell you, this is a Baptist church.

Because these three churches brought us all together, talk about, as you conclude the book, your advice for — and this is a quote — “what churches are allowed to do” in the public square, in the political square.

AMANDA: Yeah. I think there’s a lot of misunderstanding about the role that religious institutions can and should play. I think we see examples of some churches, many of which are fully bought into Christian nationalism, where the worship service looks much more like a partisan campaign rally, where you have pastors openly endorsing candidates from the pulpit, where politicians are coming to give campaign speeches.

One prominent Baptist church in my town of Dallas, Texas, has an annual patriotic Sunday around the 4th of July, where the pastor and the church have taken out billboards that say “America is a Christian nation” and that they’ll have American flags passed out to every congregant, and it’s full of patriotic songs.

So we have examples, I think, clearly of what not to do. I think sometimes churches that are interested in really pushing back against Christian nationalism might veer too far the other way, might say, I don’t want to divide my congregation; I don’t want to talk about politics at all in church; I don’t want to get involved in the life of the public square because I’m afraid my tax status might be under threat.

And so I explain in the book that there are all kinds of legal ways, ways that don’t jeopardize 501(c)(3) status, for religious institutions to be actively involved in the democracy, and I think it’s critical that all institutions and all individuals be actively engaged in the democracy.

I think that the country as a whole is on the verge of authoritarianism, and I think there are many places in this country that are already well down the road to authoritarianism, including the state of Texas where I live.

And so when I talk to crowds I say, We will only live in an authoritarian regime if we act like we live in an authoritarian regime, and as long as we have legal protections of a democracy, we have to use every piece of our democratic rights and our processes that we can.

We are sitting here, a week before a national election. Every person who is eligible needs to vote and help someone else to vote. But it’s not just happening around elections. How do we get more actively engaged in things that are going on in our local school boards, in our legislatures?

And I’m going to give you an example of what this looks like in practice in Texas. We had a law, first of its kind law, that passed from Texas last year that goes by the name the School Chaplain Law. It encouraged school districts to either hire or accept as volunteers school chaplains, and sometimes to replace mental health counselors.

You may ask, What’s a school chaplain? You know, there probably are chaplains in the audience here. I am a big supporter of chaplaincy in the right context: in the military, in hospitals, in prisons, in places where people’s access to their practice of their faith is somehow limited, that a chaplain who is properly licensed and trained to help that person follow their faith in that critical moment, that is a really critical piece of ministry.

That is not what’s happening with the School Chaplain Law. In the law in Texas, a school chaplain is defined as anyone who can pass a criminal background check, no licensing requirement, no special training, no ability to work with children, no limit on what the person can say, the school chaplain can say to kids. Proselytizing is okay. And in Texas they even rejected an amendment that would have required parental consent.

And so once that happened — the only good thing about this law is it didn’t immediately take effect. Instead, the decision-making went then to every school district in Texas, all 1,200 of them, which then had six months to decide whether or not they would start a school chaplain program.

And at that point, we at Baptist Joint Committee, working with a number of different groups, we first went to chaplains, and we told them about the law, and we organized a letter from more than 300 licensed professional chaplains who said that they did not approve of this law. They said they were offended, that they would cheapen their own professional credentials by mis-defining chaplaincy in this way, and also explained how the public school context was not the correct context for chaplains.

And so for most Texans, the first time they learned about this law was a headline in their local paper that said, School Chaplains Don’t Want Chaplain Law. And then we helped train people to go to their school boards, including a number of people who are religious leaders at different churches, to go and talk to their school board members about why they were concerned about having a School Chaplain Law that’s defined in this way in their school boards.

And out of all 1,200 districts in Texas, I know of one that voted to have a school chaplain program.

(Applause.)

AMANDA: So that is the active involvement of the faith community in pushing back against authoritarian measures that threaten religious freedom of our neighbors. And sadly, we are all going to have opportunities to do that kind of democratic advocacy — small “D” democratic advocacy — in our own contexts.

And I think it’s incumbent on us to work together and to figure out what is impacting the rights and freedoms of the people in our community and what can we do, particularly those of us who are part of a Christian majority, especially white Christians, who have, even sometimes without even reaching out and getting it, we have benefitted from white Christian nationalism in our culture.

How do we then take the responsibility of pushing back and helping create a more equitable place for all of our neighbors, regardless of religion, race, creed, ethnicity or any other line of difference?

REV. DR. LEONARD: That was an excellent way to end this conversation tonight, and I know everyone wants to thank you for the insights that you have brought to us this evening.

(Applause.)

Segment 3: We’ll see you in two weeks for our election episode! (starting at 47:45)

HOLLY: That brings us to the close of this episode of Respecting Religion. Thanks for joining us, and thanks to Dr. Bill Leonard and Knollwood Baptist Church for creating space for this conversation.

AMANDA: Visit our website at RespectingReligion.org for show notes and a transcript of this program.

HOLLY: Learn more about our work at BJC defending faith freedom for all by visiting our website at BJConline.org.

AMANDA: We would love to hear from you. You can send both of us an email by writing to [email protected]. We’re also on social media @BJContheHill, and you can follow me on X, which used to be called Twitter, @AmandaTylerBJC.

HOLLY: And if you enjoyed this show, share it with others. Take a moment to leave us a review or a five-star rating to help more people find it.

AMANDA: We also want to thank you for supporting this podcast. You can donate to these conversations by visiting the link in our show notes.

HOLLY: Join us in two weeks for a brand new post-election conversation on Respecting Religion.