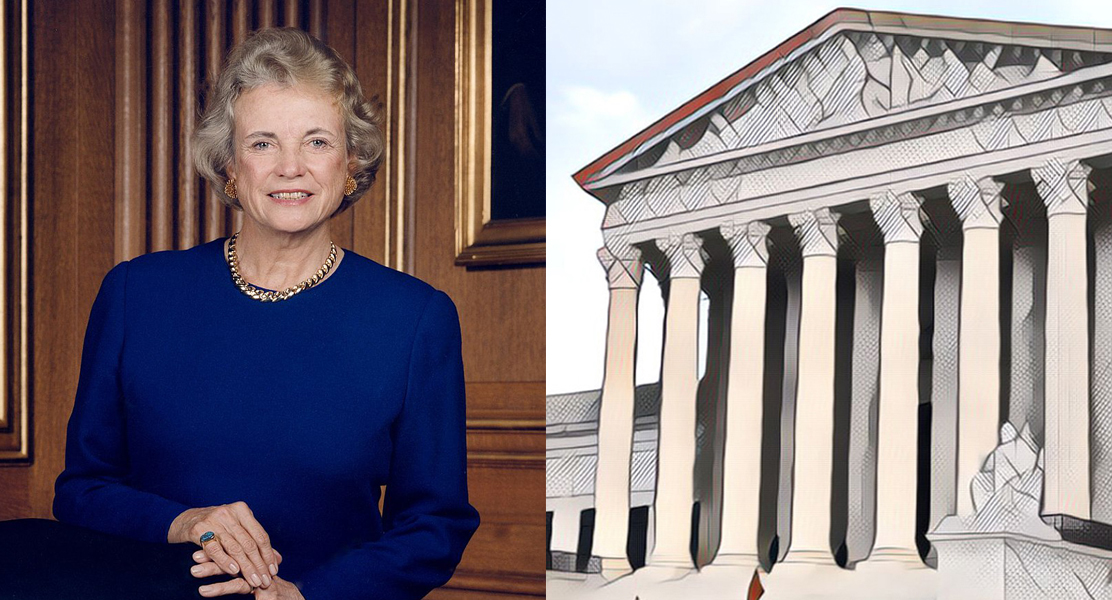

Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor leaves legacy of civic-minded church-state jurisprudence

“[T]here is a crucial difference between government speech endorsing religion, which the Establishment Clause forbids, and private speech endorsing religion, which the Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses protect.”

That’s Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in a 1990 Supreme Court opinion (Board of Education of Westside Community Schools v. Mergens), explaining in plain terms the importance of both the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause in protecting religious liberty for all. Justice O’Connor, who passed away on December 1, 2023, at the age of 93, left a remarkable legacy in church-state jurisprudence when she retired from the Court in 2006 after more than two decades as a Supreme Court Justice.

Although she did not author many majority opinions in the area of religious liberty, Justice O’Connor’s concurring opinions were unusually influential. She brought to the conversation practical, commonsense perspectives that reflected her keen awareness of the dangers to religious liberty that arise when the government appears to privilege religion.

In a 1984 concurring opinion (Lynch v. Donnelly), a dispute over a holiday display on government property, she expressed this concern by proposing an “endorsement” test as one way of determining whether a government display or action violates the Establishment Clause. The government doesn’t have to directly sponsor or impede religious activity to violate the Constitution, she explained. If the purpose of a government action or display is to endorse or disapprove of religion, or its effect is to convey a message of religious endorsement or disapproval, the government’s action infringes on the First Amendment. She writes:

Endorsement sends a message to nonadherents that they are outsiders, not full members of the political community, and an accompanying message to adherents that they are insiders, favored members of the political community. Disapproval sends the opposite message.

Justice O’Connor’s endorsement test was controversial from its beginning and never garnered a majority on the Court, but it was widely adopted by courts as one method of analysis in church-state cases, particularly those dealing with religious displays on government property. The emphasis of the endorsement test is significant. The test centers Establishment Clause protections in what she calls “the political community,” highlighting the harm that can be done to civic life when members of the public reasonably perceive a government action as privileging one religious perspective over another.

In one of the Ten Commandments monument cases decided in 2005 (McCreary County v. ACLU), Justice O’Connor elaborated on her belief that political belonging is central to the purpose of the First Amendment, insisting that the appearance that government is endorsing a religious perspective can threaten both our civic unity and our individual religious liberties. In her concurrence, she wrote:

Voluntary religious belief and expression may be as threatened when government takes the mantle of religion upon itself as when government directly interferes with private religious practices. When the government associates one set of religious beliefs with the state and identifies nonadherents as outsiders, it encroaches upon the individual’s decision about whether and how to worship.

Justice O’Connor’s vote was a deciding one in the Supreme Court’s 5-4 ruling that the Ten Commandments monument at issue in McCreary was unconstitutional. She also cast the decisive vote in Lee v. Weisman (1992), a case that struck down school-sponsored religious exercises at public school graduation as unconstitutional and affirmed the principle of government neutrality toward religion in public schools.

On the issue of government funding of religion, Justice O’Connor notably sounded a clarion call about the prospect of taxpayer money being sent directly to religious institutions, which she regarded as clearly unconstitutional. In a concurring opinion in a 2000 case (Mitchell v. Helms), she warned that the logic of the plurality opinion “foreshadows the approval of direct monetary subsidies to religious organizations, even when they use the money to advance their religious objectives.” She based much of her reasoning on her no-endorsement principle:

[I]f the religious school uses the aid to inculcate religion in its students, it is reasonable to say that the government has communicated a message of endorsement. Because the religious indoctrination is supported by government assistance, the reasonable observer would naturally perceive the aid program as government support for the advancement of religion.

Unfortunately, Justice O’Connor’s prediction about the direction of the Court on government funding of religion has largely come true, and then some. In 2022, the Court ruled that not only can the state of Maine fund religious education through its tuition program, but it must, despite state law prohibiting such funding out of Establishment Clause concerns. In response, BJC lamented the ruling:

A majority of justices on the Supreme Court keep ignoring the distinctive role of religion in law and society, which is best served by separating the institutions of religion and government. That separation, which Maine sought to protect, is an important part of America’s religious liberty legacy, and it’s a key principle for historic Baptists and others who have long championed religious liberty for all and public education.

Today’s opinion in Carson v. Makin follows a recent trend away from treating religious institutions in distinct ways to avoid government involvement in religious matters.

Justice O’Connor’s influential endorsement test has likewise been undermined, if not wholly discarded, by the current Court. In 2022’s Kennedy v. Bremerton, the Court overturned the long-standing Lemon test, which the endorsement test was meant to facilitate.

Her legacy, however, is lasting. She understood that government does no favors to religion by engaging in religious speech or by privileging one religious perspective over another, or religion over nonreligion. For all Americans to be a full member of the political community – religious adherent or not, she maintained – requires the government to steer clear of sending a message that it endorses religion. That voice is much-needed today.