S5, Ep. 02: Southern Baptist Convention president, ‘White Evangelical Racism’ author, and Respecting Religion co-host discuss Christian nationalism

The Rev. Dr. Bart Barber, Dr. Anthea Butler, and Amanda Tyler share perspectives on the dangers of Christian nationalism.

What happens when you talk about Christian nationalism with the president of the Southern Baptist Convention, a historian who wrote a book on white evangelical racism, and the lead organizer of Christians Against Christian Nationalism? Find out as we bring you portions of a panel conversation recorded in September during the Texas Tribune Festival. The Rev. Dr. Bart Barber, Dr. Anthea Butler, and Amanda Tyler talk about Christian nationalism’s connection to the January 6 attack, Baptist history, American history, Christian citizenship, and much more. You might hear surprising areas of agreement in this honest, in-depth, and animated conversation.

SHOW NOTES:

Segment 1 (starting at 02:35): Introduction to today’s show

We are playing excerpts from a conversation from the Texas Tribune Festival, recorded on September 22, 2023.

The participants are:

- Amanda Tyler, executive director of BJC, lead organizer of Christians Against Christian Nationalism, and co-host of Respecting Religion

- Rev. Dr. Bart Barber, president of the Southern Baptist Convention and pastor of First Baptist Church of Farmersville, Texas

- Dr. Anthea Butler, the Geraldine R. Segal Professor in American Social Thought and chair of the Religious Studies Department at the University of Pennsylvania. She is the author of White Evangelical Racism: The Politics of Morality in America

- Moderator Robert Downen, Texas Tribune reporter covering democracy and threats to it; previously, he covered religion at the Houston Chronicle

Amanda shared a video clip of the conversation on her X account, which you can view here.

The Bloudy Tenet of Persecution was written by Roger Williams in 1644.

Segment 2 (starting at 11:59): The overlaps of Christian nationalism

Read more about the push in Texas to install public school “chaplains” at this link: BJConline.org/publicschoolchaplains

Segment 3 (starting at 19:24): The draw of Christian nationalism and Christian involvement in politics

Dr. Butler’s book is White Evangelical Racism: The Politics of Morality in America.

You can read the Southern Baptist Convention’s statement of faith at this link. Article XVII is about religious liberty.

Segment 4 (starting at 31:23): Christian nationalism in churches and in politics

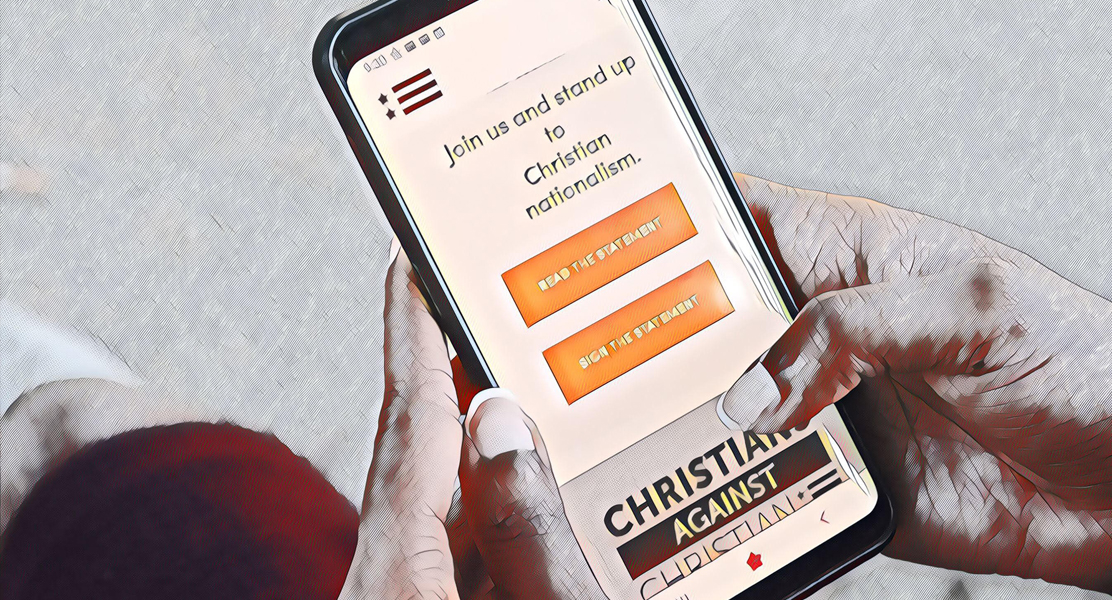

Read the Christians Against Christian Nationalism statement and learn more about the campaign at this link.

Segment 5 (starting at 37:21): Christian nationalism and the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol

Read the report on Christian Nationalism and the January 6, 2021, Insurrection at this link. It was produced by BJC and the Freedom From Religion Foundation, and features contributions from Amanda Tyler and Dr. Anthea Butler, along with many others.

Read the letter submitted to the January 6 Select Committee from Christian leaders at this link.

Watch Rep. Jared Huffman’s floor speech about Christian nationalism here.

Watch Amanda Tyler’s testimony to Congress on Christian nationalism here. She discusses it in episode 9 of season 4 of Respecting Religion.

Segment 6 (starting at 43:51): Differences in Christian nationalism and faith-based advocacy

Read the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” at this link.

Respecting Religion is made possible by BJC’s generous donors. You can support these conversations with a gift to BJC.

Transcript: Season 5, Episode 02: Southern Baptist Convention president, ‘White Evangelical Racism’ author, and Respecting Religion co-host discuss Christian nationalism (some parts of this transcript have been edited for clarity)

Segment 1: Introduction to today’s show

HOLLY: Welcome to Respecting Religion, a BJC Podcast series where we look at religion, the law, and what’s at stake for faith freedom today. I’m Holly Hollman, general counsel at BJC.

Today, we’re bringing you a special episode focused on the threat of Chrisitan nationalism.

We’ll be playing excerpts from a panel at the Texas Tribune Festival in Austin last month featuring Bart Barber, the president of the Southern Baptist Convention, in conversation with Anthea Butler, chair of the Religious Studies Department at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of White Evangelical Racism, alongside my Respecting Religion co-host Amanda Tyler.

The festival is an annual event that brings together thought leaders from across the country to discuss a wide variety of topics.

The two panelists who will be speaking alongside Amanda are no strangers to BJC’s work. The Southern Baptist Convention was one of the organizations that helped create BJC in 1936. BJC and the Southern Baptist Convention as organizations parted ways in the early 1990s, and we have significant differences in how we view religious freedom today. But we work together on occasion – particularly where we agree and where our shared voices can make an impact. We both continue to espouse our Baptist heritage and what we sometimes call “Baptist distinctives” – particularly support for the institutional separation of church and state.

Meanwhile, Dr. Anthea Butler was one of the contributors to the report on Christian nationalism and the January 6 insurrection that BJC published with the Freedom From Religion Foundation – we’ll put a link to that in our show notes.

We are bringing you this conversation with three people all of them concerned about Christian nationalism, but each approaching it from a specific and different point of view. The moderator of the conversation is Robert Downen, a reporter who covers democracy for the Texas Tribune.

It was standing-room-only for this panel at the festival, and we want to thank Texas Tribune for allowing us to play parts of the conversation in today’s Respecting Religion episode.

Now, here’s Robert Downen to kick off the conversation:

(Applause.)

MR. ROBERT DOWNEN: So I want to start with Amanda. Tell us a little bit about what BJC does, and, you know, we have two representatives from two Baptist organizations here, and I would love to hear a little bit more about the traditional Baptist stance on church-state separation and, you know, why that is ‑‑ you know, how it is different from what we are seeing with respect to Christian nationalism today.

MS. AMANDA TYLER: Yeah. So we could spend all day talking about what is a Baptist. But Baptist is ‑‑ one thing to know, there’s no such thing as the “Baptist church.” There’s a Baptist movement, and there are so many different expressions of what it means to be Baptist. But through the centuries ‑‑ and Baptists date their beginnings to the beginning of the 17th century – through the centuries, one thing that has united Baptists in all these different expressions is a commitment to religious freedom for everyone, not just for Baptists, and an advocacy that goes straight to advocacy for the government or the state to say the state has nothing to do with religion or religious practice.

In fact, one of the co-founders of the Baptist movement, a man named Thomas Helwys, gave his life to this advocacy for religious freedom and advocating to King James – of the “King James Bible” fame.

So BJC is a modern-day organization, 87 years old, headquartered on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., that are the modern-day heirs to this Baptist legacy of religious freedom advocacy. And we believe that the best way to protect religious freedom for everyone in the American context is to defend the constitutional principle of the separation of church and state, which simply means that the church doesn’t try to do the job of the state, and the state doesn’t try to do the job of the church.

And we have fought this for decades. And over recent years, we have come to see that the single biggest threat to religious freedom for everyone and to this principle of church-state separation is this ideology of Christian nationalism that tries to merge American and Christian identities in a way that would privilege Christianity over other faiths and would also have the state involved in religious matters in a way that harms religious freedom – not just for those who aren’t Christians but for Christians as well, because whenever the state gets involved in religious matters, it is religion that comes out on the short end of that stick.

MR. DOWNEN: Sure. And, Bart, give me the theological argument against Christian nationalism.

REV. DR. BART BARBER: Thank you. It’s great to be here today. I do think that that’s important for us to point out, that really three cases have been made for religious liberty down through the years. We’ve argued with other Christians to suggest to other Christians that Jesus would want us to extend religious liberty to everyone around us, a biblical case.

You have – Roger Williams would be a good example of someone who did that. People like Isaac Backus who made a narrative case to their neighbors, to persuade their neighbors for religious liberty, and then people like John Leland, James Madison, who made a political case to rulers for why it benefits the country to have religious liberty.

And in the case of Christian nationalism, we need to make that biblical case to try to persuade people who are fellow Christians that it’s important for us to give liberty to all those who are around us.

Two places that that shows up: One, people that move into Christian nationalism tend to treat the relationship between the Old Testament and the New Testament differently from the way that Baptists have tended to do so. You can either look at the Old Testament on sort of an Andy Stanley model and say, We’re just going to unhitch it and get rid of it and ignore it completely. You can come to the model that’s more prevalent among, say, Presbyterians, to find a great deal of unity between the Old Testament and the New Testament.

Baptists have tended to say, the Old Testament teaches us some important things; it tells us some things about who God is and about what right and wrong is, but the pattern for the church and for the way the church endures in society is found in the New Testament and not in the Old Testament. And so it’s important to make that case to show that Christianity is something different – that the rules for Old Testament Israel about enforcing faith upon those who are in the country is not something that applies to us.

And lastly I’d just say in the New Testament, you find a definite indication that there’s something different. The apostles, after Jesus had resurrected and before he went to heaven, one of the last things they asked him is, So are you going to inaugurate the kingdom now? And Jesus’ response to that was, Why are we even talking about that? You’ll know when it’s time; let’s go on to something else.

So Christians are ‑‑ it’s eschatological. We’re waiting for that day in the book of Revelation where it says, “The kingdoms of the world have become the kingdoms of our Lord and of his Christ.” And in the time of that waiting, Jesus told a story, a parable, an analogy, the parable of the wheat and the tares that has been a classic text that’s been used to defend religious liberty in that Jesus said that in that story, he was saying that the world’s mixed, that there are people who are followers of the Christian faith, there are people who are not.

There’s an impulse sometimes among people who are followers of the Christian faith to say, We got to do something about all these people who are not followers of the Christian faith. And in that story, Jesus has God saying, No, not your job; you don’t know how to do it; you’re going to hurt people if you engage in that sort of thing. And so that’s one of so many places.

Roger Williams in The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution cited all but six books of the Bible, making a biblical case, a religious case, against the idea of combining church and state and punishing people because of their doctrine.

MR. DOWNEN: Sure. And, Anthea, we see a lot of ‑‑ I have ‑‑ if Christian nationalism, the ultimate cultural project, is to have a society in which Christians are dominant and society is generally Christian, one would think that Christian nationalism would be rushing to say, Open the southern border and bring in people who are overwhelmingly Christian. And yet that doesn’t happen. And I’m wondering if you can kind of talk about the racial undertones of Christian nationalism and Christian nationalism as a stand-in in many ways for ethnocentrism.

DR. ANTHEA BUTLER: Well, let’s go.

(Audience laughter.)

DR. BUTLER: Now, I want to start ‑‑ since Bart wanted to talk about Scripture, let’s talk about Jesus who looked at the Syrophoenician woman and didn’t want to give her anything. Even Jesus could be a little bit ethnonationalist, so let’s start there. That’s number one. If we want to put this on Scripture, let’s put it there. That’s number one. You all go read your Bible. All right?

So let’s go to this other thing about who gets to come in and who doesn’t get to come in. And part of this has to do with the racism of this country, the foundation of this country. Our Founders and Framers, some of them were slaveholders. And when we have to start to think about who comes in, we have to think about who got brought in first to come in and do the work. That were enslaved Africans. Okay?

And so we got to start at that point, because you can’t even talk about the immigration problem until we think about the first problem that started off this nation which was slavery. And when we don’t talk about that in conjunction with what we are doing at the border to put up ‑‑ excuse me ‑‑ razors in the water to cut people off, people. Jesus said, Welcome the strangers. So we don’t put this in Scripture, because I’m a church historian, too.

Let’s talk about how Christians are persecuting people who just want a better life, who want to come into the country through both illegal and legal means to do this. And so what I’ve been thinking about is what is the problem with the Christians that we have right now who are against immigration. If that would have been the case, when Mary and Joseph were trying to find a place so that they could lay their head, in America they wouldn’t have been able to get over this border, because they would have had to cross that water. She would have been birthing Jesus on the side in the desert somewhere.

So when we talk about all of these things, we have to remember that this country has always had a bad history about immigrants. I live in Philadelphia. We had German immigrants; we had Italian immigrants; we had immigrants from other countries. And every piece of those people who came in had to fight with other people who were already here.

The problem is for us right now is that we see whiteness and Christianity as synonymous, and when that happens, then you lose what the Christian message is all about. And I want to say one more thing, Bart, because I think this is really important. When I hear people talk about this stuff ‑‑ you talked about Old and New Testament, but did you talk about what Jesus said? Welcome the stranger.

And this is the issue. We are not welcoming to the stranger. We have policies that are put in place by people who yell every day how much they love God and how much they want Christianity and how they want to bring the kingdom of God into earth, and all they’re doing is bringing hell.

(Applause.)

Segment 2 (starting at 11:59): The overlaps of Christian nationalism

HOLLY: You’ve been listening to excerpts of the Texas Tribune Festival’s panel on Christian nationalism, featuring my co-host Amanda Tyler in conversation with Southern Baptist Convention President Bart Barber and Dr. Anthea Butler, author of the book White Evangelical Racism.

In this next excerpt, Amanda begins by discussing the overlap between white supremacy and Christian nationalism. Let’s listen back in.

MS. TYLER: I think we have to talk about Christian nationalism and white Christian nationalism in the sense that Christian nationalism does provide cover for white supremacy and racial subjugation. It uses the Gospel as respectability for the racism, for the exclusion, and that’s because that Christian nationalism tells a narrative about who really belongs here, and it relies on this “Christian nation” mythology to say that true belonging belongs only to the people who had power at the beginning of the country.

And that’s because it has this role of God’s providential hand guiding America through history. It says, not as John’s Gospel says, that God so loved the world. It says that God so loved the United States, that God has a special role for the United States. It’s all part of this “Christian nation” narrative. But you can’t pick and choose from history, as Dr. Butler said.

You have to remember that, of course, we have this history of slavery that has undergirded the entire American experiment, the entire American story, and so you can’t say that God’s hand is only at work in part of the American story and not the rest. And so that’s how it provides cover.

And I’ll give you an example. There’s something again more respectable about some of the language and symbols of Christian nationalism where we don’t have the same kind of acceptability for explicitly racist symbols anymore. State flag of Mississippi is an example of this. Until 2020, there was Confederate battle flag as part of the state flag of Mississippi.

In that year, the legislature of Mississippi said, yes, finally, voters, you can vote on whether or not you want to remove the Confederate flag from our state flag, but only if you replace it with a flag that includes the words “In God we trust.” We take this coded symbol of Christian nationalism and replace more explicit racist language.

And part of the reason for that is because the “Christian” in Christian nationalism is much more about this ethno-national identity than it is about theology or religion. That is not to say that Christianity itself has not been impacted by Christian nationalism over the centuries.

Christian nationalism did not come onto the scene in the last decade or even in the last 200 years. It’s been around for a much longer time, and so that’s a more complicated, I think, theological question about how much Christian nationalism has impacted Christianity, but racism and white supremacy is so tied up into this entire conversation, we can’t have a conversation without talking about it.

MR. DOWNEN: Sure. And just to follow up, you mentioned, you know, religious symbols in public. We are in Texas where just this year, there was a bill passed that allowed unlicensed chaplains to supplant the roles of mental health counselors in public schools. There was another bill that did not make it out of the legislature this year that would have required the Ten Commandments to be posted in every single classroom, and we are also, you know, in many ways, I think ‑‑ well, I’ll take the people driving the movement. They see in Texas a model for what they say is an infusion of religion into public life.

And I’m wondering if you can kind of walk through some of the legal developments that have created this environment where those types of things are not only possible but increasing in ‑‑ we’re seeing more of them in statehouses across the country and this kind of, you know, what we could almost call soft Christian nationalism that may not be on its face Christian nationalist, but does allow for the erosion of a strong church-state separation.

MS. TYLER: Yeah. I think it’s really vital that we talk about not just the most explicit forms of Christian nationalism we see but also the more everyday forms and how public schools are being targeted for a lot of this Christian nationalist legislation. And it didn’t just start this year, but it has certainly accelerated.

So for several years now, we’ve seen these bills that have been put forward by a group called the Congressional Prayer Caucus Foundation. Those are the bills that, for instance, require the posting of In God We Trust in public schools.

And we see another round this year where we see Texas legislature, for example, taking advantage of confusion sown by the United States Supreme Court in some of their recent decisions that have eroded the longtime protections for church-state separation, particularly in the public school context. And so there’s confusion about exactly where the line is now.

And so legislatures like Texas are going to say, well, we’re going to make the argument that there’s no line anymore, so we’re going to go back, long-standing precedent, for instance, that said that we would not post the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms, and we’re going to test the Supreme Court now and see where that is. We’re going to try to pass that law.

The school “chaplain” law, again, first of its kind, passed the Texas legislature, went into effect September 1, just a few weeks, and it requires every school board in the state of Texas to have a vote within the next six months about whether the schools will have school “chaplains” in their schools.

Where did this come from? I mean, this is a problem in search of a problem. Of all of the pressing issues facing Texas public schools, to say this is the piece of legislation we’re going to pass, and so now we have school boards starting to vote on it. Well, I’ll tell you where it came from. It came from a group called the National School Chaplains Association. That is a group that is a subsidiary of a group called Mission Generation.

If you go to Mission Generation’s website right now, it just will redirect you to the National School Chaplains Association, but if you look at the Form 990 for Mission Generation, they tell you what their aim is. Their aim is to disciple a hundred million children into the faith through the use of school chaplains. And so they are going to statehouses and asking school boards to allow school chaplains into their buildings so that they can proselytize and convert young people.

If this is not an incursion on religious freedom and parental rights, I do not know what is. And yet we have the state of Texas passing this first-of-a-kind bill, and now we’re seeing people in Texas saying, This is not what we want. We have chaplains, professional chaplains, saying, This is not what chaplaincy is about; this is not what the public school context should be – sponsoring chaplains. And so we’re seeing resistance at the school board level for this policy being put in place, but we’re also seeing copycat legislation in other states.

So I think we need to be really attuned for the ways that church-state separation is being eroded, and that is a problem for everyone’s religious freedom rights.

Segment 3 (starting at 19:24): The draw of Christian nationalism and Christian involvement in politics

HOLLY: We’ll have much more on the effort to replace school counselors with unlicensed chaplains on an upcoming episode of Respecting Religion.

Now, let’s pick back up after moderator Robert Downen of the Texas Tribune asked Bart Barber of the Southern Baptist Convention about what he thinks makes Christian nationalism attractive to evangelicals.

REV. DR. BARBER: So there’s recent research that shows how many of the people who are engaged in Christian nationalism don’t attend church anywhere, and it’s really a striking number of people who do that. I think when you get to people who actually are faithfully reading the Bible, they’re living as disciples, they’re trying to grow in their faith – there are moderating influences there that are important.

The Southern Baptist Convention ‑‑ it may surprise you to know this, but – the Southern Baptist Convention, at a meeting ‑‑ I drove from Nashville to here yesterday to be at this – and in the meeting at Nashville, the Southern Baptist Convention declared not to be a friendly cooperating church in our convention, a church where a pastor appeared in blackface and also dressed up as a Native American woman and was very unrepentant about that – went on the news, talking about how everybody needed to get a sense of humor.

So, there are a lot of things ‑‑ one reason why evangelicalism is attractive here is because you can become an evangelical just by answering a pollster and trying to pick what you are. You don’t actually have to be someone who attends church in any way.

And the more you attend church, the more you’re likely to go on a mission trip and experience the rest of the world.

The more you attend church, the more committed you are to it, the more likely you are to be engaged in something like the Southern Baptist Convention that’s actually one of the most racially diverse fellowships of churches in the entire country. It’s made up of hundreds of different ethnicities and nationalities, and so you encounter people like that who are a lot different from you.

And to be a part of something like the Southern Baptist Convention, we have the second largest disaster relief response group in the country, and so my wife, who’s very involved in disaster relief child care, she’s been overseas, taking care of children in the aftermath of natural disasters.

All of those things make it very hard for you to stick with something that is kinist or that is white supremacist or anything like that when you go beyond just choosing a label and saying, Well, I know I’m not Catholic, and I don’t want to be an atheist; I don’t really go to church; maybe I’m an evangelical. And I think there’s a strong sense of support among people like that for this kind of Christian nationalism.

MR. DOWNEN: Sure. And I’m wondering, you know ‑‑ Dr. Butler ‑‑ I’m sorry; I’ve been calling everyone by their first names. You know, evangelicalism has for decades, if not, you know, longer, framed itself very much as at war with the culture, the secular culture. And I think in so many ways, you know, with respect to your response, I think that it does ‑‑ you know, your response is framing it within the context of the Southern Baptist Convention and the religious aspects of it, whereas I think that equally if not more important to the insidiousness of Christian nationalism in those spaces is the rhetoric that is on its ‑‑ you know, that type of culture war rhetoric.

And I’m wondering, Dr. Butler, if you would like to respond to kind of, you know, the way that evangelical movements in particular have framed themselves over the last few decades and how that ties into broader ‑‑ you know, the underlying white supremacy and the spread of Christian nationalism in those spaces.

DR. BUTLER: Let’s go back and do a little history lesson. Okay. I’m going to try to do this in like about three minutes. I hope I’m going to get there. Okay?

So when we have the association of national evangelicals that was birthed in the 1940s, the first biggest thing that evangelicals had to fight against was communism. Okay?

And when communism came out, everybody was like, you know, if you are someone who is looking at civil rights or fighting for civil rights, you got labeled as a communist. Okay? And so this is the first great battle that is happening.

And the great battle for evangelicals back then was the fight against, one, communism, the UN, all of that stuff, and then we got to civil rights. Right? And so it used to be that everybody would just say ‑‑ I want to pick up on one thing that Bart said, talking about what evangelicals are naming themselves. It used to be that somebody said, anyone who is an evangelical liked Billy Graham. Okay? And that made sense back then. That made sense. It doesn’t make sense now.

But when you get to the ’60s, it started to be school prayer. Right? And you get to school prayer and all of those issues in the ’60s, alongside of civil rights. In the ’70s, you have a couple of things, and this is a bigger thing you can read in my book, but I talk about how they have to pivot from civil rights because they realize integration is going to happen, so we start to soften that a little bit. And what’s the next thing you move to – courtesy of Paul Weyrich – you move to abortion. And then you move from that into, you know, homosexuality, feminism, all this stuff. This is a long, long, long history. Okay? So you can’t just say this. And then in the ’90s, it’s like, you know, basically we’re going to be mobilizing ourselves.

But alongside of this, what was interesting that happened? You think about all of these people. Lots of people who were, you know, Baptist and others back then might have been Democrats, but then they moved into the Republican Party. And then we get to Bush in 2000 who said his favorite philosopher was Jesus. That got everybody in. Okay? So Shrub ‑‑ I’m going to say that in relation to one of my favorite people ‑‑ and if you know who that is, you know who it is. And then you get to 2008, and you get a Black president.

Now, I’m going to talk about one thing that happened during that that really struck me. One of the people that wrote this like crazy letter – which is no longer published but I have a copy of it – was James Dobson, and he talked about the dystopian world that was going to happen because there was going to be a Black president. Do you know how high gun sales went after that election happened? They zoomed through the roof. Okay? And then we got birtherism, and we got all of this stuff.

So these culture wars that started off as morality turned into political action, and that’s what my book is all about. It’s about how these people have used morality as a shield for political and social power and being able to support what they don’t want in the culture. And so you can talk about culture wars as being biblical, but if you do that, you miss the political action that is happening.

So while I totally believe that there are people within the Southern Baptist Convention and churches that are, you know, living right and doing missions work and everything else ‑‑ I mean, I know these folks. Some of them are really great.

But the fact of the matter is when your people go en masse to go vote in ways that counter the gospel because they want to live their lives the way they want to and they don’t want those people living by them or they don’t care who has to work at Taco Bell or something else because these jobs should be for other people and not for those people, then I have to question, What is the use of saying culture war when actually what the war is about is a war for power.

And we have to see that culture is being used as a way to say, oh, we don’t want this, but actually these moral issues have been used as wedge issues to pull the nation apart and to break civic engagement.

(Applause.)

MR. DOWNEN: Would you like to respond at all?

REV. DR. BARBER: Sure. I’d be happy to. So our statement of faith in the Southern Baptist Convention has Article XV that talks about the Christian in the social order and Article XVII that talks about religious liberty. When you put those two things together, I think they make a pretty powerful rationale for engagement in culture.

It is true that the same Baptists who have tried to protect religious liberty have also advocated for our point of view at the ballot box, have advocated for our point of view in Congress. The Baptist Joint Committee is an example of a Baptist group created to advocate for public policy, including advocating for religious liberty.

The fact is our country was started with religious liberty at the federal level, but many of the colonies, many of the early states had a Christian establishment that persecuted people who believed what I believe. Massachusetts didn’t disestablish until 1835. And the reason we have disestablishment is because people who supported religious liberty also advocated for public policy.

And there are a lot of people who have done that. I think that the abolition movement was a movement of Christians in many ways ‑‑ William Lloyd Garrison, Lyman Beecher, Harriet Beecher Stowe: these were all people who, on the basis of their theological perspective, worked to change American law. Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail” – very much something that tried to persuade Christians who needed to be persuaded on the basis of their theology – sought to use Christian theology to persuade Christians to support civil rights.

When people go into the voting booth, they’re either going to vote based on personal gain, what will bring more money into my pocketbook over the course of this year, or out of some sort of party jersey that they’re wearing to say, What will advantage my side and penalize the other side, or they’re going to vote based on the idea of what’s best for my neighbors. And when Christians go into the voting booth and vote, I want them to vote on what’s best for their neighbors, just that they can’t turn off their Christian beliefs as a part of what shapes their understanding of what’s best for their neighbors.

And our Article XV says that we should do that. We should be engaged in culture and in politics to try to advocate for what’s best for everyone as we’re informed by Christianity to think that. But then Article XVII says, but we don’t do that by penalizing people for their religious belief, but we should instead support the idea of a free church and a free state that does not try to use the means of government for the advance of the Gospel.

I think those two ideas are highly compatible. We’ve lived in accordance with those for 400 years as Baptists. And so I think that the kind of narrative that suggests that everything is suspect when evangelicals start going into their political lives as citizenship with an idea of their faith ‑‑ I think the idea that that’s suspect is naive and actually would rob American history of some of the best things that have happened in American history.

Christian citizenship is not Christian nationalism.

Segment 4 (starting at 31:23): Christian nationalism in churches and in politics

HOLLY: You’ve been listening to a back-and-forth between Bart Barber, president of the Southern Baptist Convention, and Anthea Butler, author of White Evangelical Racism. My Respecting Religion co-host Amanda Tyler gets into this conversation now about Christian involvement in politics.

MS. TYLER: I agree with that last statement, but I think more and more we’re seeing Christian citizens show up as Christian nationalism, and I think it’s because ‑‑ you know, it’s important to point out that to be against Christian nationalism is not to be against faith-based advocacy. To be against Christian nationalism is to be against a kind of advocacy that insists on your own theological view being reflected in law and policy and as being something that should be imposed on everyone else.

But the problem that I think we’re seeing ‑‑ and not just in white evangelical spaces but in a lot of other Christian spaces as well ‑‑ is that we’re finding houses of worship that are not teaching Christianity, but they’re teaching Christian nationalism. They have gotten so far away from the gospel of love and instead are worshipping a false idol of power. It’s not every house of worship, but it is present in, I would say, most houses of worship to some degree.

And that’s the work that we’re doing at Christians Against Christian Nationalism – is asking Christians to first look inside their own faith communities and themselves, and say, Where has Christian nationalism impacted my theology, my worship practice? You know, what exactly are we worshipping here?

And so when I think about ‑‑ I agree that, and I actually think the polling on this is somewhat mixed. You find in some polls that the more people are in church, the less likely they’re being indoctrinated in Christian nationalism, but other polls show that the more likely you’re in church, the more likely you’re being indoctrinated into Christian nationalism. And so I think that we have to look at what’s happening.

And we can look right here in the state of Texas at the God and country worship services that happen at First Baptist Dallas as an example of Christian nationalist worship, that’s happening in a place of worship. And so there are certainly examples of that, and I think that’s what impacts the ballot box, because your values that you’re voting are not necessarily Christian values. They’re Christian nationalist values.

MR. DOWNEN: Dr. Butler, I believe it was in 2016 Donald Trump really, I think ‑‑ a key part of his ascendancy to ‑‑ I shouldn’t say ascendancy ‑‑ his win to the Oval Office ‑‑ sorry ‑‑

(Audience laughter)

MR. DOWNEN: — was his vow that Christianity will have power underneath him. I mean, to what degree do you think that he made good on that promise, and to what degree do you think that is ‑‑ you know, that is going to be a factor going into 2024?

DR. BUTLER: There are some people who are not going to like my answer about this, but Donald Trump gave them everything they asked for. Now, I’m just going to just put this down and make it plain. Okay? Whatever you say about Donald Trump, Donald Trump gave Christians and explicitly the evangelical sort of group ‑‑ and I’m using the word “evangelical” loosely. We’re going to get into that later, I hope, so I can say a little bit about what I think that word means now.

He gave them everything. He gave them three, you know, Supreme Court justices, and we have seen the result of what that means. You know, abortion’s basically gone. You know, when Wendy Davis stood in her tennis shoes ‑‑ thank you very much ‑‑ over here in the capitol, talking about abortion ‑‑ right? ‑‑ everybody back in 2012 was like, this is not going to go away. And the historian in me was going like, It’s just a matter of time.

So I wasn’t surprised when that thing leaked – back, you know, whenever it was last year or however. It was the end point of all of this. And that’s how Donald Trump still has the amount of power that he has. It is because he made the promises that he knew he needed to make. Whether or not he believed them is a whole other thing altogether.

But when you have people calling him “King Cyrus” and saying that he’s God-ordained and drawing him with Jesus standing behind him at the Oval Office desk ‑‑ that’s the worst picture ever ‑‑ okay? ‑‑ just the worst. I don’t even know who drew it, but I just want to go like, Never draw again. Okay? Don’t take a pen in your hand.

(Audience laughter.)

DR. BUTLER: This is why you can think that Donald Trump is divinely ordained. It doesn’t matter what he says. It doesn’t matter what he does. He gave them what they wanted, which was this power and authority. And so now what you have are people parroting all the things that he does. And so when he was over here in Waco ‑‑ right? ‑‑ you know, embarrassing even the Branch Davidians with his ‑‑ now, that’s a lot, right? ‑‑ with this QAnon mess, this is where we just opened up this can of worms.

And so I think the question is about this – and this is where I want you all to think about this as you leave here today. The question is not whether it’s the Southern Baptists or the evangelicals or whatever. The question is: Do we want a theocracy in this country or do we not want a theocracy, because that’s where this is. It’s not in this sort of, you know, namby-pamby little thing right now. It’s about, do you want theocracy, or do you want democracy. That is the question for 2024.

And that is a shame to have to ask it like that, because, see, you know, I know the Southern Baptist history and everything. This is fine. People are going to believe what they believe. But now this is impinging upon our civic engagements and rights and what people can do and not do with their own bodies, how their kids are going to be in school. But they’re telling you that this has to happen so we can take care of your kids better than you are. And this is not right.

Segment 5 (starting at 37:21): Christian nationalism and the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol

HOLLY: In this segment, the conversation shifts a bit to focus on Chrisitan nationalism and the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, as well as the difficulties and misunderstandings that can arise when we discuss what it means to confront and combat Christian nationalism.

We’ll start with moderator Robert Downen again, as he poses a question to Amanda and Dr. Butler. This comes after he noted that any talk of Christian nationalism was absent from official reports about the January 6 insurrection.

MR. DOWNEN: Can you tell me a little bit about the role that Christian nationalism played in the insurrection and why you are so concerned about its omission in the broader story we are telling ourselves about that day?

MS. TYLER: I mean, I just don’t think we can ever understand what happened on January 6 if we don’t grapple with Christian nationalism. It’s not the only thing that drove it, but it is what helped intensify the attack and made it into the just absolute horror that we all witnessed live on television that day. And that’s because Christian nationalism and Christianity used religion as permission structure for what they were doing.

It made their political actions and wrapped it in not only God’s favor but God’s direction, that they were following God’s direction to save democracy. And so it united all these disparate actors who were there from all different kinds of groups and conspiracy theories and hate groups, and it gave them a common cause, a common vocabulary, symbols. And it didn’t just happen on January 6, as we know from watching all of the prosecutions. This was a well thought out plan, and the Christian nationalism was a part of it throughout.

And BJC co-produced a report on this topic with Freedom From Religion Foundation, and it is the single most comprehensive accounting to date of all of the ways that Christian nationalism played into January 6, including in all of those rallies and events leading up to it. And so we produced this report in February of 2022, sent it to Congress. That was when the Select Committee was meeting. The Select ‑‑ and Dr. Butler contributed to that report, as did some other scholars who are studying this phenomenon, this ideology.

And then Congress invited all of our testimony and said, We want to learn more about this, the Select Committee. So we submitted all of our testimony, and then we watched all of those hearings, just waiting for them to question about Christian nationalism. And the only time that Christian nationalism showed up in the hearings was when one of the witnesses said, you know, I believe the Constitution is divinely inspired.

And then Rep. Liz Cheney repeated from the dais, Thank you for reminding us that the Constitution is divinely inspired. So instead of attacking Christian nationalism, we heard Christian nationalism furthered in the hearing room.

And so I was really disappointed but not surprised when the report came out and they didn’t mention Christian nationalism, and that’s because I think it remains this political taboo to talk about Christian nationalism, because members are afraid that you’re attacking Christianity when you do it.

And that is why ‑‑ that is what motivates the advocacy of Christians Against Christian Nationalism, is for people who are Christian to say, No, no, I want you to talk about Christian nationalism because it’s a gross distortion of my faith. But it remains pretty much an off-limits topic in Congress, with a couple of exceptions.

I want to say Rep. Jared Huffman made a floor speech about Christian nationalism, and then Rep. Jamie Raskin actually invited me to provide testimony to his subcommittee on Christian nationalism and white supremacist violence. But those two instances remain two of the only instances of Christian nationalism even being uttered in the Congressional record.

DR. BUTLER: Let me just take this a little step further. Let’s go back to December ’20. December ’20 there was a Jericho March throughout Washington, D.C. That is where most of this planning happened. That was also the day a Black Lives Matter sign was pulled down in front of one of the historic Black churches in Washington, D.C.

Who were part of these Jericho Marches? It wasn’t just like ‑‑ you know, we can’t blame this on evangelicals. There were all kinds of Christian people that were there who had been called in. Who was part of that? Paula White. Who opened up the day on January 6? Paula White praying. Okay? So, you know, I’m ready for Paula White to get hauled in in front of something ‑‑ all right? ‑‑ because this has been somebody who’s very close to Donald Trump, his preacher.

But I bring that up because part of what you need to hear right now is that it’s not just about a culture war. It is a battle. The way that this kind of Christian nationalism is being put forth now is in the area of violence, taking America back by force, talking about people being demons. Okay? And so when you start to hear this rhetoric out here from different political leaders or different religious leaders, it’s ‑‑ again, it is not a question of whether this person is a Baptist or not. It’s a question of what kind of Christianity are they promoting. And more likely than not, they are promoting Christian nationalism.

And so if you look at some of the images from that day of 1/6 – which was a horrible day for this nation – a lot of the imagery was Christian imagery. There is a guillotine that I wrote about that had Christian images pushed on the side of it. This is a great thing. If you follow me on Twitter, you can DM me or throw a thing at me, and I will answer you and show you where this is, because there was so much Christian imagery that day about how to take this place back for God.

And in the prayer that happened in the Senate chamber, that guy’s already in jail. He’s kind of a, you know, New Age person, this shaman, so to speak. But that was prayer in the Senate that was just an abomination. I’m sorry. And so when we talk about these things and I think about how many people have died for this country and everything else – to put this in the guise of we’re doing this for God is ridiculous.

(Audience Applause.)

Segment 6 (starting at 43:51): Differences in Christian nationalism and faith-based advocacy

HOLLY: In this final excerpt from the conversation, moderator Robert Downen begins by posing a question to Rev. Dr. Bart Barber, following up on something from earlier in their discussion.

MR. DOWNEN: You mentioned, you know, “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” and in it, you know, MLK ‑‑ it is a letter written to white pastors, criticizing them for the anesthetizing security of stained glass windows.

And it does seem that far often than not, Christians have been very slow to critique each other on Christian nationalism and very fast to critique each other when it comes to what we think of these more culture war issues or other things. And I’m wondering, you know, I’m thinking even back to my first meeting at the Southern Baptist Convention that I attended in 2018. There was a robust conversation about whether or not to let Mike Pence speak that day. And that does kind of feel like a bygone era almost in some ways. And I’m wondering why you think it is ‑‑

REV. DR. BARBER: Which feels like a bygone era?

MR. DOWNEN: I guess I shouldn’t say that. That was an unfair characterization. But ‑‑

REV. DR. BARBER: Well, I just didn’t understand what you’re saying.

MR. DOWNEN: It doesn’t seem like a lot of ‑‑ you know, the conversation that happened over Pence in 2018, I think, would be something that would be much more difficult to have in a lot of evangelical spaces these days. And I’m wondering, all three of you ‑‑ I would love all of your answers on this ‑‑ why you think it is that so many Christians have been so slow to confront each other when it comes to Christian nationalism or things that leaders all understand to be a perversion of the gospel and much more willing and able to confront each other when it comes to these, quote/unquote, culture war or political issues.

REV. DR. BARBER: I’ll say I really disagree with the premise.

MR. DOWNEN: Okay.

REV. DR. BARBER: We haven’t had a single politician come speak at the Southern Baptist Convention annual meeting since Mike Pence came, and ‑‑

MR. DOWNEN: Let me rephrase that ‑‑

REV. DR. BARBER: — and we’ve had major conflict and division in the Southern Baptist Convention because of the large number of people in the Southern Baptist Convention who have expressed alarm about this very sort of thing.

The fact is you have three people on this panel, all of whom affirm separation of church and state, all of whom affirm religious liberty, all of whom are worried about Christian nationalism, all of whom are writing and speaking to encourage people away from that. But respectfully, Anthea, if you’re going to make it about being a Republican or about defending unborn life or about things like that, suddenly the opportunity to have three people who are united, who could all speak against this, that is broken because ‑‑

DR. BUTLER: Who broke it? Who broke it? This is the question, because, you know, respectfully, I am going to say to you, as a Catholic woman sitting up here, that there is disagreement within my denomination about this stuff, too. We are going to disagree. We can’t agree on everything. It’s not going to happen, not where we are right now. But the ground that I come to at this particular thing is: Do you want theocracy, or do you want democracy?

REV. DR. BARBER: Well, if Christian nationalism is just about opposing theocracy, we’re on the same side. If it’s about you have to affirm Roe v. Wade, suddenly we’re not on the same side anymore. If Christian nationalism ‑‑

DR. BUTLER: I never said you have to affirm it. ever.

REV. DR. BARBER: If Christian nationalism is support for defending vulnerable people like that in the country, then ‑‑ if you’re going to define Christian nationalism that way, suddenly I, who was opposed to Christian nationalism, am one. And so ‑‑

DR. BUTLER: You’re misunderstanding what I’m saying.

REV. DR. BARBER: Okay.

DR. BUTLER: You’re misunderstanding what I’m saying.

REV. DR. BARBER: Well, I misunderstand folks all the time. That’s probably right.

DR. BUTLER: Yeah. But I’m just saying to you, you can be as pro-life as you want to be, but what I am saying is that these kinds of beliefs are seeping into Christian nationalism, and it’s hard to untangle all of this. And if we got a room full of people here, as an educator, what I’m here to do is tell you that you need to be a lot more careful about what you’re hearing and what you’re seeing and how to describe that.

I would never tell you not to believe what you believe, because I know what your theology is. Okay? Unfortunately, your people who are sitting in your churches don’t know your theology. That’s the bigger problem right now.

REV. DR. BARBER: That’s probably true of every church ‑‑

DR. BUTLER: Yeah. That’s really true right now ‑‑

REV. DR. BARBER: — that the people don’t really ‑‑

DR. BUTLER: — because they don’t know what they believe. But the question is here, is I bring all of those things up to say, if we’re going to talk about moral issues, which is what Robert was asking about, the culture war issues and everything else, this was part of the culture war. You have to bring that up. But now that that’s over, where have we moved next to? Trans kids. We’ve moved next to getting people out of their homes and their kids apart from each other. How far does this go? Is this ‑‑

REV. DR. BARBER: Well, that’s what people on the other side are asking, too. How far does this go?

DR. BUTLER: How far does this go, and is this going to be part of what we consider to be a nationalistic idea or a religious idea or what? And that’s the thing. I don’t know that people understand those distinctions.

REV. DR. BARBER: I think a good place for us to be is outlined in our statement of faith, just to say that whatever your faith is or even if you’re someone who doesn’t have any faith, you should have the same access to government and voting and representation as somebody like me or anyone else. That’s the ideal that we’ve advocated for for 400 years. But we’ve also along the way said that includes access for people who believe like us as well as people who don’t believe like us.

I’m committed to that. I tell you, I put my job on the line. I lost a lot people from my church in 2015, defending the rights of Muslims to build a cemetery in our small town in Texas. So I’m a true believer when it comes to religious liberty for everyone, and I’m stubborn about it.

But I also believe that even if you’re a conservative, pro-life Republican, that just because your faith shapes some of the way you feel about that doesn’t mean that you can’t advocate for it, that you can’t vote for it, that you can’t try to persuade other people around ‑‑ the difference between Christian nationalism and Christian citizenship is I want to persuade you. I don’t want to change the Constitution in order ‑‑

DR. BUTLER: But how do they persuade?

REV. DR. BARBER: — to push you out of being able to vote.

MS. TYLER: And I think that’s the problem that we’re seeing is how we see our modern day pluralism running up against Christian nationalism which is trying to preserve authority for those who are white and Christian. And so that’s why I said the difference between faith-based advocacy and Christian nationalism earlier.

The difference is Christian nationalism insists on one particular theological view, and so when we see, for instance, in some of the abortion bans, Scripture being used as justification for the new law, that’s an example of Christian nationalism.

DR. BUTLER: Exactly.

-music-

HOLLY: Thanks again to the Texas Tribune for allowing us to play excerpts from that conversation during this podcast today.

We want to thank Robert Downen, Rev. Dr. Bart Barber, and Dr. Anthea Butler for engaging in such an important discussion, bringing their full selves and perspectives to this event.

For more information on this program and topics discussed, visit our website at Respecting Religion dot org for show notes and a transcript of this program.

Respecting Religion is produced and edited by Cherilyn Guy, with editorial assistance from Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons and Jennifer Hawks.

Learn more about our work at BJC defending faith freedom for all by visiting our website at BJConline.org.

We’re also on social media at BJContheHill, and you can follow Amanda on X – which used to be called Twitter – at @AmandaTyler BJC. She even posted a video clip of this conversation, which is in our show notes.

We also want to thank you for listening and supporting this podcast. You can donate to these conversations by visiting the link in our show notes.

Join us on Thursdays for new conversations Respecting Religion.