S5, Ep. 18: A chief justice or chief theologian for Alabama?

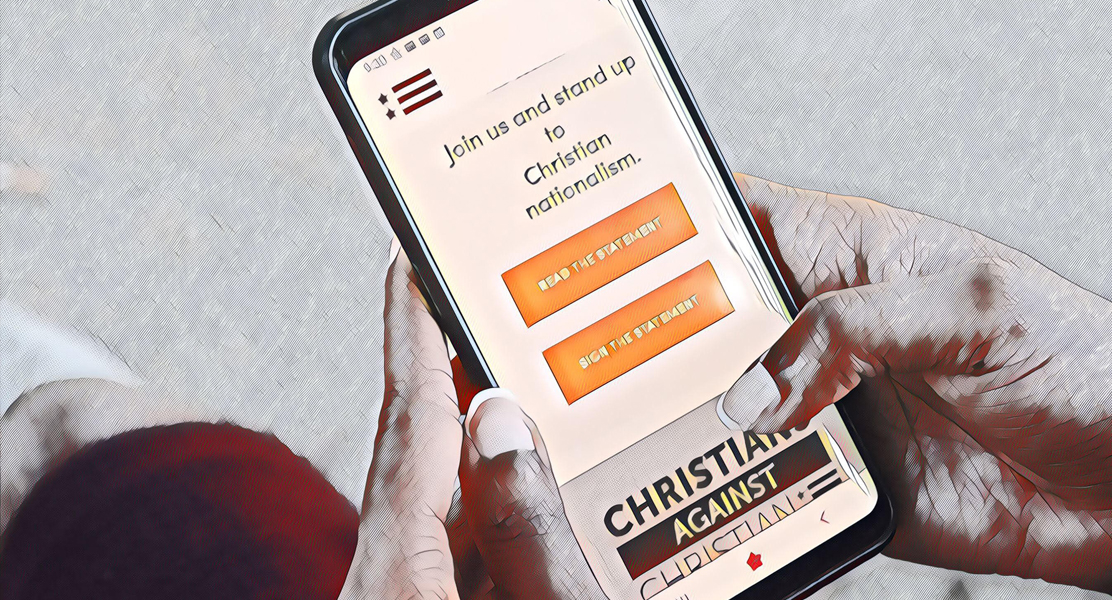

Amanda and Holly share why the government should not interpret laws based on one religious view.

An alarming ruling from the Alabama Supreme Court is leading to the shutdown of in vitro fertilization clinics, and the concurrence’s use of Scripture and Christian theology is causing additional concerns. Amanda Tyler and Holly Hollman look at this troubling ruling, the various religious views on life, and why it’s an issue for a justice to cite the Bible in an opinion.

SHOW NOTES:

Segment 1 (starting at 00:38): What is the Alabama case about?

The Alabama Supreme Court case is called LePage v. Center for Reproductive Medicine. You can read the decision and the concurrence here.

For additional information on the case, listen to the NPR interview with law professor Mary Ziegler in this story: How Alabama’s ruling that frozen embryos are ‘children’ could impact IVF

Amanda and Holly discussed the Dobbs decision in episode 4 of season 4.

Segment 2 (starting at 13:18): The decision and even more-troubling concurrence

Listen to the “On the Media” interview with Matthew D. Taylor: Christian Nationalism is Reshaping Fertility Rights, and Books Dominate at the Oscars

Amanda talked about her experience at the ReAwaken America tour in episode 22 of season 4 of Respecting Religion.

Segment 3 (starting at 31:15): Additional reactions to the opinion

Read the entire piece by Noah Feldman for Bloomberg at this link: Embryos Are Now Children in Alabama. Blame the Supreme Court.

Amanda and Holly discussed the Kennedy v. Bremerton decision in episode 21 of season 3.

Respecting Religion is made possible by BJC’s generous donors. You can support these conversations with a gift to BJC.

Transcript: Season 5, Episode 18: A chief justice or chief theologian for Alabama? (some parts of this transcript have been edited for clarity)

Segment 1: What is the Alabama case about? (starting at 00:24)

AMANDA: Welcome to Respecting Religion, a BJC podcast series where we look at religion, the law, and what’s at stake for faith freedom today. I’m Amanda Tyler, executive director of BJC.

HOLLY: And I’m general counsel Holly Hollman. Today, on this Leap Day episode of Respecting Religion, we respond to an alarming judicial ruling out of the Alabama Supreme Court. The Court held that frozen embryos are children and therefore could give rise to a lawsuit for wrongful death.

AMANDA: This decision from the Alabama Supreme Court is concerning, and as church-state law experts, we are particularly upset about a concurring opinion from the Court’s chief justice that was chock-full of Christian nationalism.

HOLLY: There is a lot to discuss here. What’s at stake in this case and why we oppose justices citing the Bible and Christian theologians is what we want to talk about today on Respecting Religion.

Okay, Amanda. Let’s first start with a brief description of the case. The case is LePage v. Center for Reproductive Medicine. And to get a short, concise summary of the facts, let’s start with an NPR interview with UC Davis professor of law Mary Ziegler. I’ll note that Professor Ziegler has written and speaks extensively on the topics of law, history, and the politics of reproduction and really is one of the world’s leading historians of the U.S. abortion debate. Here’s how she described the case.

PROFESSOR ZIEGLER: (audio clip) There were three couples that had pursued in vitro fertilization treatment at a clinic in Mobile, Alabama, and at a point in 2020, a hospital patient — the hospital was operated by the same clinic — entered the place where frozen embryos were stored, handled some of the embryos, burned his hand, dropped the embryos, and destroyed them, and this led to a lawsuit from the three couples.

They had a variety of theories in the suit, one of which was that the state’s Wrongful Death of a Minor law treated those frozen embryos as children or persons. And the Alabama Supreme Court agreed with them in that in this Friday decision.

AMANDA: Well, thanks to Professor Ziegler and to NPR. We thought that that provided a great summary of the facts and gets us more quickly today, Holly, to our reactions about this case and what’s at stake.

HOLLY: But, of course, we have to say one of our reactions is to the facts, because this case is so novel that I think it presents for the first time an opportunity for many people who have not considered this part of reproductive health, presents all these questions. How does it work? What does it mean? How do you do it? And what are the implications of that? And so we start off by knowing that there are embryos that are frozen and under the care of these private facilities.

Now, of course, you and I aren’t experts on reproductive health or IVF treatments, but we are both women, and we have children, and we know something about the complex nature of women’s reproductive health care, and so we’re not surprised that this decision has elicited all kinds of reaction. In my mind, it was mind-blowingly maddening, because there was just so much here that can be problematic.

Before we discuss more about the decision and the reactions to it, let’s hear more from Mary Ziegler on NPR about one of the most immediate practical implications of the case.

PROFESSOR ZIEGLER: (audio clip) Well, if Alabama IVF providers feel obligated to implant every embryo they create, that’s likely to both reduce the chances that any IVF cycle will be successful. It also might make it a lot more expensive. IVF is already very expensive, I think the average being between about 15,000 and $20,000 per IVF cycle.

“Many patients don’t succeed with IVF after one cycle. But if you were not allowed to create more than one embryo per cycle, that’s likely to make IVF even more financially out of reach for people who don’t have insurance coverage and who struggle to pay that hefty price tag.

AMANDA: So, Holly, we think that that entire interview with Professor Ziegler is worth listening to, and so we’re going to include in our show notes a link to that story for our listeners.

But what really strikes me about her description of the real-world impact of this case is how deeply personal these decisions are. In order — you know, because of scientific advancements, pregnancy is an option for many people for whom pregnancy had not been an option before IVF existed. And these are personal decisions for the people involved in choosing pregnancy in this way, with their health providers. It is often a big financial decision for people to make, and, Holly, frankly, it’s none of your or my business what people are doing when it comes to their in vitro fertilization. And yet, it has become worldwide news —

HOLLY: Right.

AMANDA: — in the wake of this decision from the Alabama Supreme Court that has us all now very involved in thinking through all of the implications for this very personal decision.

HOLLY: Right. You can kind of see the personal nature of this, just implicit in that short paragraph that we played, talking about cycles of IVF treatment. So this has to do with personal bodily processes that women go through and how to then retrieve the eggs from the body, and then the process to go through that to result in an embryo and to understand that that is so technical.

In addition to being so personal, Amanda, I think it’s so scientifically technical. And you can imagine how many questions are involved in this and running a business that’s involved in that. Amazing amount of detailed information that one would need to decide to go through this: the physical; the emotional; as you said, the financial; and the legal implications that, for some people the first time they’re thinking about it, they’re thinking that the Alabama Supreme Court is going to bluntly decide how this is going to go.

AMANDA: Yeah. And we have to understand — we are going to talk specifically about Alabama and Alabama law here. But we would not be having this conversation, I do not think, were it not for the Dobbs decision from the U.S. Supreme Court two terms ago. Of course, that decision overturned the precedent, a 50-year precedent, of Roe v. Wade, and really started on this whole conversation about government being more involved in decisions of pregnancy.

And there are so many different ramifications from that decision, and I think this is the first major case — right? — where we see how implications for the abortion rights conversation and debate can actually go into the area of in vitro fertilization and other issues arising out of pregnancy.

HOLLY: Yeah. And because this deals with the definition of child and person, it extends the conversation that we’re used to hearing in the abortion context about when life begins. And we know that that question raises significant issues to discuss about, you know, church-state law, what we know about when and how the government interacts with religion. It raises the issue of the importance of legal definitions, and it forces us to recognize the many theological perspectives on when life begins and, you know, how a decision like this affects all of us.

While this case only deals with Alabama law — it is interpreting an Alabama statute, and it’s considering in the backdrop the Alabama Constitution — it’s important for us to discuss it, because similar arguments are being made about the rights of a fetus or an embryo in other states and this idea that sometimes is referred to as a theory of “fetal personhood,” and it’s a theory that some would also pursue under the U.S. Constitution as well.

AMANDA: That’s right. And in the post-Dobbs era, this theory of fetal personhood has really taken off as the next step in the pro-life movement of banning all abortions. And so whether it is in the context of abortion or, as we have here, in vitro fertilization, or other medical issues that concern fetuses and embryos, how the state defines when life begins becomes much more important for these other legal questions.

HOLLY: And it’s all rather, as I said, maddening, because we’re having this legal conversation about words and their meaning and Alabama law. But this involves something that should be a matter for medical professionals, for patients under the care of health care providers, taking into account all the different things that are involved in women’s health.

And so I’m sorry. I just needed to say that before I proceed in a lawyerly manner here, that this is really a hard conversation, because we know it affects real people. We are zooming in on one particular aspect of a much larger conversation we should be having about protecting people in our country and making sure that we take care of women and children in the many ways that are appropriate for public policy.

AMANDA: Right. And as lawyers, we know the power of the legal system, and using that power here to get involved where it should not be involved, where we firmly believe that these are decisions for medical professionals, for patients to be making, and that the legal system should be involved as little as possible. And yet we have this really uncharted territory that we’re in now where the legal system is becoming more and more involved in these highly personal medical decisions.

HOLLY: We know, of course, these issues are important to religious communities, such as in our own Baptist churches, and we should start this discussion by recognizing a diversity of views that exist among and within religious traditions about not just abortion but IVF and the beginning of life.

AMANDA: Right. Not all religions agree on how we define when life begins. In fact, Jewish tradition does not give embryos the same legal status as a person, and most Jewish scholars believe that life begins when breath is first drawn, that is, upon birth.

HOLLY: And there’s a scriptural basis for that view. Of course, there are a lot of different ways to view this, and there are a lot of ethical, moral complications, different ways to think about it.

I co-teach the church-state law seminar at Georgetown University Law Center with a Catholic law professor, and in our discussions and in teaching, we know that it’s important to note that there are very different understandings of human sexuality and when life begins that implicate church-state law.

That has implications for what courts decide as a practical matter, not just for the policymakers but for people, for medical professionals that serve patients in incredibly complex medical situations.

AMANDA: Right. I mean, I think the bottom-line point, as we’re starting off here, is there is no one religious view, and yet the problem in Alabama, as revealed in this case, is that the interpretation of law is based on one narrow religious view, and the Alabama Supreme Court has just imposed that one view on everyone, with very serious consequences that are far from expected from courts or supported by most people.

Segment 2: The decision and even more-troubling concurrence (starting at 13:18)

HOLLY: Well, let’s look a little bit more closely at this decision. Again, the case is called LePage v. Center for Reproductive Medicine. It involves multiple plaintiffs. You can read the full decision — we can link to it in the show notes. It’s about 130 pages, but we’re going to hit the highlights here today.

AMANDA: Or lowlights.

HOLLY: Or lowlights. But this case is out of the Alabama Supreme Court. It was decided on February 16, and it relies on a statute, a state law from 1872, that allows parents to sue over the death of a minor child, and it applies, quote, “to all unborn children, regardless of their location.”

And just to set this up, I think I should read how this begins, because you can just feel — well, it tells us where the Court is going in very direct terms. The decision is written by Justice Jay Mitchell, and it begins this way.

“This Court has long held that unborn children are ‘children’ for purposes of Alabama’s Wrongful Death of a Minor Act. That statute allows parents of a deceased child to recover punitive damages for their child’s death. The central question presented in these consolidated appeals, which involve the death of embryos kept in a cryogenic nursery, is whether the Act contains an unwritten exception to that rule for extrauterine children — that is, unborn children who are located outside of a biological uterus at the time they are killed. Under existing black-letter law, the answer to that question is no: the Wrongful Death of a Minor Act applies to all unborn children, regardless of their location.”

AMANDA: Okay. When I was reading the decision at this point, Holly, I was like, am I reading a decision from a state supreme court or am I reading a science fiction novel? I mean — and I was also starting to doubt my own conception of reality here. I mean, “extrauterine children.” This is the first time I’ve ever heard that phrase, and if someone asked me, I would just imagine that that is a child once they have been born from a uterus.

I have never thought — and I still don’t think — that there is a way that a child can be born if they are not in a womb. Right?

HOLLY: Right.

AMANDA: Okay. Just wanted to be sure, because the Alabama Supreme Court —

HOLLY: You are not crazy.

AMANDA: — has started me to question reality and my understanding of physical processes of birth.

HOLLY: Well, I think that’s one of the immediate reactions people had is, what are you talking about, extrauterine children? And the idea that these embryos are children is, you know, startling. Even in the best circumstances here, what we’re talking about is being able to join an egg and a sperm and create an embryo in a situation where the person who wants this baby has not been able to do that, and that this is extremely difficult and tenuous.

And it also involves implanting that embryo in the womb in order to have the possibility of then turning into a pregnancy. Everything else has to go well along the way to then eventually achieve a healthy birth. And so there’s a lot more to the process, but absolutely there has to be the process of putting the embryo in the uterus in order for this to be even — even a possibility.

And your reaction, Amanda, is the same as mine. It’s like, you know, you’re not done. We don’t have children yet, because you’ve begun this process outside of the body.

AMANDA: Outside of a person’s body. I mean, we’re forgetting, I think, about — in this quest for fetal personhood, we are forgetting — or in this case, embryo personhood — we’re forgetting about the very real importance of the person who is carrying that child in their womb.

HOLLY: So, yes. Extrauterine children is not something that we typically think about or language that we would typically use.

AMANDA: It’s not a thing, but the Alabama Supreme Court has created it as such. So, Holly, as you mentioned, the entire case, when you include all of the different opinions, is pretty long. It’s 131 pages. But the analysis of this court’s opinion is actually quite short and, I would say, quite thin.

The Court starts by saying, “The parties to these cases have raised many difficult questions” — because this is a difficult case; that’s my aside — “including ones about the ethical status of extrauterine children, the application of the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution to such children, and the public-policy implications of treating extrauterine children as human beings. But” — conveniently — “this Court today need not address these questions because, as explained below, the relevant statutory text is clear: the Wrongful Death of a Minor Act applies on its face to all unborn children, without limitation.”

And, you know, I think — here ends the reading. But what makes this so disturbing to me is this wrongful death statute is from 1872, long before there ever was such a thing as in vitro fertilization. So for the Court to declare that this is a clear statute on its face as applied to these modern facts, these modern circumstances, is not at all clear. And meanwhile, they are just blowing past all kinds of ethical questions and public-policy implications.

And what we’ve seen in the short time since this decision has come out is how this has really thrown into question in the state of Alabama the availability of in vitro fertilization for all people there who have come to rely on this scientific advancement in order to try to get pregnant.

HOLLY: The Court seems satisfied just with its finding that unborn children are, quote, children under the act, without exception, based on developmental stage, physical location, or any other ancillary characteristics, is how they look at it.

So after noting some of these important and complex arguments that have been brought up, they pretty much put them aside pretty quickly and just decide this as a matter of statutory interpretation, looking at a couple of earlier Alabama cases, just to show that there’s some precedent that unborn children are children, and then from there, they take this big leap that the same status is given to these embryos.

Then that is what has the big implications for the Center for Reproductive Medicine and others who are involved in IVF and basically shut this down for a while, because you got to figure out now, okay, wait, this changes how we see embryos. This changes our responsibility and how we take care of them, the processes by which couples decide if they discard them or they do something else once they don’t need the embryos anymore.

And, you know, that change in the law is something that if you’re running this kind of business or if you’re a couple involved in this process, it really turns things upside down, so we got to put on the brakes and, you know, that has a lot of costs, not just financially but personally.

Well, we’ve summarized the majority opinion and stated, you know, how the Court made its decision based on the text and its assumptions and understanding, putting aside all these difficult arguments. What we should talk about now is this concurrence, and this concurrence by Chief Justice Parker is what’s getting all the news.

And we should note, first of all, you know, you don’t have to write a concurrence. A concurrence is something a judge or justice does to add something to the majority.

So not satisfied with the decision that takes a very, in our view, extreme view of the definition of “child” to include these embryos, he goes much further to say why that is the right decision and tells us a lot about his thinking.

AMANDA: He does, and I think that we can speak for many people, saying we really wish that he had not added this concurrence. But it does give us, I think, an important window into how religion is playing a huge role in the way at least Chief Justice Parker participated in this case.

And right off the bat, he says, “A good judge follows the Constitution instead of policy, except when the Constitution itself commands the judge to follow a certain policy.” This public policy that Chief Justice Parker cites here was voted on and adopted by the people of Alabama to amend the state constitution in November 2018.

And I’ll read that, as he says, declaration of public policy. “This State acknowledges, declares and affirms that it is the public policy of this State to recognize and support the sanctity of unborn life and the rights of unborn children, including the right to life.”

HOLLY: Clearly, Amanda, that provision, you know, can be read as saying, okay, this is an extreme anti-abortion kind of amendment that the state of Alabama has passed. But this decision in LePage goes beyond that. And so it’s not even clear — well, it’s clearly not assumed by the reaction in Alabama of how quickly people were saying, Oh, wait, this doesn’t mean that we’re going to shut down IVF clinics. It shows that this language was not supposed to go so far beyond, you know, making abortion more difficult and more unlikely in Alabama.

AMANDA: Well, it’s not at all clear that this was ever contemplated by the voters when they adopted this language — that they would think that this would apply to in vitro fertilization, but through this decision, these justices have done just that.

And so then Chief Justice Parker leads us on a kind of winding road that starts with defining what “sanctity” means, and then when he defines it as having some kind of sense of holiness, of life and character, Godliness, the quality or state of being holy or sacred, then he says, Aha, I guess then we need to turn to Scripture in order to understand what the people of Alabama meant here.

And this is where this decision, which is already, I think, kind of beyond the bounds of what we might have imagined, this is where it really goes off the rails, in my opinion —

HOLLY: Yeah.

AMANDA: — because he starts citing from Scripture, from theologians, from Thomas Aquinas, and incorporates that all into the legal reasoning, using theological text as legal reasoning in a decision that applies to the people of Alabama.

HOLLY: He basically asserts that by using that language in its state constitution, that the voters already decided that they are looking to the Bible to base their law on.

AMANDA: We want to read two key passages in this concurrence to really show the breadth of the use of religion to justify the chief justice’s concurring opinion in this case.

First, he writes, “In summary, the theologically based view of the sanctity of life adopted by the People of Alabama encompasses the following: (1) God made every person in His image; (2) each person therefore has a value that far exceeds the ability of human beings to calculate; and (3) human life cannot be wrongfully destroyed without incurring the wrath of a holy God, who views the destruction of His image as an affront to Himself.”

HOLLY: Holy moly. Yeah, that’s pretty extreme and not at all what we are used to seeing in judicial opinions. And he doubles down on that as he concludes this concurring opinion, because he’s basically making the case not only that in his view, this decision is correct and it is in line with his thinking about scripture, but that this basis, this religious basis for the law, is the public policy of Alabama. And I think that’s where we’re going to have some really interesting discussions in the future.

But he ends his opinion by saying, quote, “The People of Alabama have declared the public policy of this State to be that unborn human life is sacred. We believe that each human being, from the moment of conception, is made in the image of God, created by Him to reflect His likeness. It is as if the People of Alabama took what was spoken of the prophet Jeremiah and applied it to every unborn person in this state:” — and now quoting from Jeremiah — “‘Before I formed you in the womb, I knew you. Before you were born, I sanctified you.’ Jeremiah 1:5.”

He goes on to say, “All three branches of government are subject to a constitutional mandate to treat each unborn human life with reverence. Carving out an exception for the people in this case, small as they were, would be unacceptable to the People of this State, who have required us to treat every human being in accordance with the fear of a holy God who made them in His image. For these reasons, and the reasons stated in the main opinion, I concur.” Wow.

AMANDA: I mean, this is unlike any judicial opinion I have ever read, Holly, and it caused me immediately to ask this question: Who is this Chief Justice Parker? Where are these views coming from? I know this has been a topic of conversation on a lot of news outlets and a lot of other podcasts.

And I heard an excellent interview on the podcast “On the Media” with an expert, Matthew D. Taylor, who talked about how this Chief Justice Parker is part of this larger movement called the New Apostolic Reformation, which has gotten a lot of coverage recently in some other conversations around Christian nationalism. And so we’ll link to that podcast in our show notes. I really recommend that conversation for more context.

But suffice it to say that this New Apostolic Reformation is a very extreme form of Christianity and an extreme form of Christian nationalism. It has a lot of overlap with something called dominionism and something called the seven mountains mandate, which basically says that Christians should overtake every segment of society, including the government.

And this is a worldview that Chief Justice Parker has embraced, and we see him in his position of elected authority in the state of Alabama using that in order to enforce his religious views on the people of Alabama in his interpretation of this case.

HOLLY: Well, Amanda, I’ll remind you, you definitely met some of these people when you attended the ReAwaken America Tour in Miami. If anyone listening now hasn’t heard that podcast episode, they can go back and hear it. But I think it is more jarring to read that in a judicial opinion from the chief justice of a state supreme court.

In reading that last part of his conclusion, when he used that very beautiful Scripture from Jeremiah in this way, it struck me as manipulative and, you know, something that he would like to take for granted that he knows what that Scripture means, and he knows how to apply it today, and it’s pretty offensive.

It’s offensive to me as someone who cares about Scripture and who knows something, not everything, but knows something about the history of Christianity and use of the Bible and understands that Scripture can be used a lot of different ways for different ends. And that’s part of the reason we don’t want the government to interpret laws based on Scripture.

AMANDA: That’s right. He was elected by the people of Alabama to be chief justice of the supreme court, not to be chief theologian for the state of Alabama. They’re different roles, and he should stay in his lane and leave Scripture interpretation for religious authorities. It’s not the job of the government.

Segment 3: Additional reactions to the opinion (starting at 31:15)

HOLLY: Well, we, of course, were not alone in reacting very strongly to this opinion. Not only did it upset people in Alabama and around the country and around the world and make people ask a lot of questions, there was one important op-ed that we saw by Noah Feldman in a Bloomberg opinion column. He’s a professor of law at Harvard University and someone who has spent quite a bit of his scholarship on constitutional issues relating to church and state, and he said, quote, “In my 30 years studying the constitutional relationship between church and state, I can’t recall any legal opinion that more expressly relies on Christian theology to interpret American law.”

So here this is a scholar who has systemically kind of been doing this work, noting what we’re reacting to, Amanda. It certainly felt like that to us. And in his column, he goes on to kind of question why that might be. You know, we’ve been talking about it as just a problem of Alabama state law, and that is primarily where it is.

We should note, as other court-watchers have noted, that this case may end in Alabama. The ideas won’t end. We’ll see them other places. They’ll be debated. But this is not a case that necessarily would go up to the U.S. Supreme Court. But this article that Professor Feldman wrote talks about how this does relate to the current U.S. Supreme Court.

AMANDA: And we, Holly, have talked about how this Court and recent decisions from it have called into question what the Establishment Clause means and how to apply it in different cases. And Professor Feldman in his piece talks about the Kennedy v. Bremerton case, a case that we’ve covered at length on Respecting Religion, and he says Bremerton was as revolutionary for its own area of law as Dobbs was for reproductive rights.

I think — again, we won’t rehash the facts of the Bremerton case here, except to say that it has called into question what tests are still applicable for the Establishment Clause. And I think one thing that we’ve said — and we can debate that — but at the very least, at the very least, what remains of the Establishment Clause is a rule that there won’t be government coercion when it comes to religion.

And I think one of the ways that we’ve understood government coercion in other contexts is that there would be no religious laws, that no one religion would be used for law or policy or to justify law or policy.

And so this opinion, and specifically the concurrence from Chief Justice Parker, is really questioning that principle and really pushing the bounds of what remains of the Establishment Clause, and that is very alarming for the two of us, Holly, but also, I think, for so many other people who are court-watchers and who have, you know, come to rely on this promise in the Bill of Rights and the First Amendment about how we protect everyone’s religious freedom by being sure that the government isn’t enforcing one religious view on everyone else.

HOLLY: We’ll link to that article in the show notes as just one way to look at this and what is at stake for faith freedom for all, what’s at stake for religion, law and public policy, particularly in this moment where the Court has abandoned earlier tests that were used to uphold Establishment Clause principles, and instead, you know, really left things to lower courts to look kind of broadly at history and tradition without a lot of guideposts to protect religious freedom in the way that we understand that it should be protected under our constitutional tradition.

That brings us to the close of this episode of Respecting Religion. Thanks for joining us. For more information on what we discussed, visit our website at RespectingReligion.org for show notes and a transcript of this program.

AMANDA: Respecting Religion is produced by Cherilyn Guy with editorial assistance from Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons.

HOLLY: Learn more about the work of BJC, defending faith freedom for all, by visiting our website at BJConline.org.

AMANDA: We’d love to hear from you. You can send both of us an email by writing to [email protected]. We’re also on social media @BJContheHill, and you can follow me on X, which used to be called Twitter, @AmandaTylerBJC.

HOLLY: And if you enjoyed this show, share it with others. Take a moment to leave us a five-star rating to help other people find us.

AMANDA: We also want to thank you for supporting this podcast. You can donate to these conversations by visiting the link in our show notes.

HOLLY: Join us on Thursdays for new conversations Respecting Religion.